Curse of Ham Curse of Ham

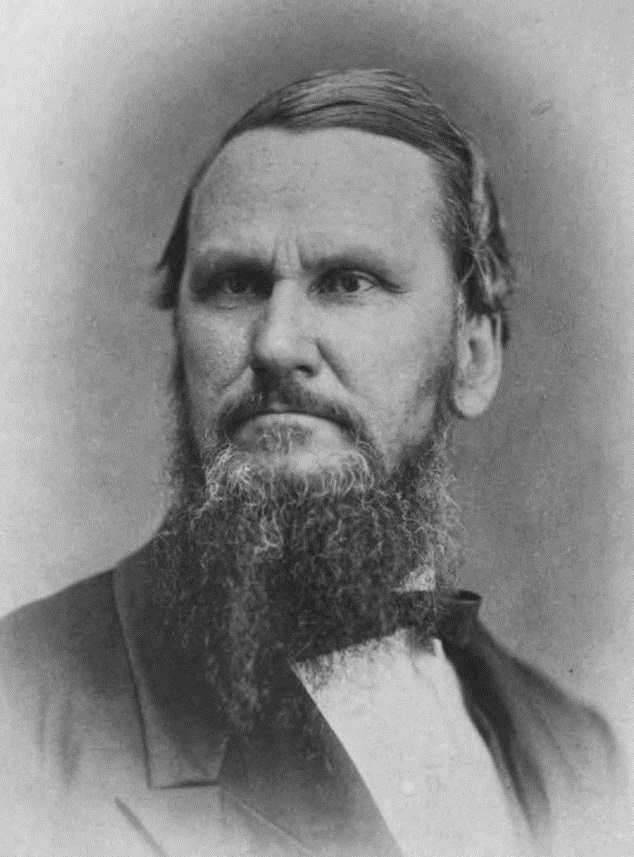

Robert Lewis Dabney felt Moses' law was simply irrelevant to the

Christian: ". . .and he [God] also gave, by the intervention of Moses,

various religious and civil laws, which were peculiar to the Jews, and

were never intended to be observed after the resurrection of Jesus

Christ." (Robert Lewis Dabney, Defense

of Virginia and the South, Kindle location 1364). Moses' law is just

irrelevant, to him. Moses' law limited servitude amongst Israelites to

six years. What is truly bizarre about his argument, and brazen in its

shamelessness, though, is that not only is he not willing to counsel his

fellow Southerners to abide by God's decree of six years and out, he

finds in the law the raw material for a pro-slavery case, because the

law mentions slavery. The law allows servitude for a term of six years.

Well, if slavery were 'malum in se,' evil in itself, then it would not

be tolerated for even a minute, now would it, much less for six long

years? So slavery is not evil 'in itself,' and thus the way is cleared

for permanent life-long slavery! And this claim is solidified and proven

by God's instructions limiting servitude to six years. Is this brilliant

logic, dear Reader, or sophistry of rare brazenness?

We as Christians should not simply dismiss the law, because it

reveals God's mind on a variety of issues. We do not live under

the Mosaic code as our civil law, but any law code we write for

ourselves ought to be at least as fair, and as just, as was Moses'

law code. So when you get down to cases, Dabney's dealings

with the Old Testament are worse even than mere

dismissal of the law would be. Moses is summarily dismissed, but he

doesn't stay dismissed, he gets called back. Not only are these laws of release in no way relevant

to the church, the Israel of God. . .but the mere mention of bondage in the

language of these laws constitutes an absolute and unbounded permission

for life-long slavery, forever! Because you see, if bondage were wrong 'in

itself,' it would not be permitted even for six years. And since

it's not wrong 'in itself,' you can drop the six year limitation!

There's manifestly a fallacy here; it's probably sorites. Piling one

straw more on the donkey's back does not cause him to collapse beneath

the weight; but what is a ton except one straw plus one straw plus one

straw? What is labor law but specifying, 'this many hours, and not that

many hours.' It takes a very special person, like Douglas Wilson, to

look at this argument and think it's brilliant. It's obviously wrong.

According to the argument, if slavery were 'malum in se,' evil 'in

itself,' it would be prohibited altogether and not limited to six years.

But God is not opposed to employment. He is against oppression. He is

against exploitation. How does employment turn into these things? It may

be by such insensible additions as when the load of straw on the

donkey's back accumulates to the point where it crushes him. What was

the straw that broke his back? Who knows, but life-long slavery is

certainly too long, which is why it's actually illegal. Dabney could

have told the Southern public that. He knew that's what God's word says.

He did not.

It is impossible to wrap one's mind around

Dabney's tap-dancing sophistry: these laws don't apply to us, and not only that but

they give the Southern slave-owner unquestioned permission to hold

non-foreigners in perpetual bondage! As we've seen, he states very plausibly, "Doubtless,

the standard which they had in view, in commanding masters to 'render to

their servants those things which are just and equal,' was the Mosaic

law." (Robert Lewis Dabney, Defense of Virginia and the South, Kindle

location 1864). Doubtless, indeed; but he has no intention of advising

anyone to observe the Mosaic law, with its time limit for servitude of

six years; he immediately explains that the slave-owner has "a right to

the slave's labor for life," (Robert Lewis Dabney, Defense of Virginia

and the South, Kindle location 1864), which is quite simply not what

Moses said. This is not an honest effort to understand the Bible. These

rapacious, avaricious people wanted what they wanted, and they could

not have cared less what God had said about it.

Dabney believed that the Jacobin spirit persisted; triumphant in the

Civil War, the Jacobins proceeded to offer the franchise to the newly

liberated slaves, which resulted in disaster from his standpoint:

"Argument is scarcely needed to demonstrate that the

infamous reconstruction measures were taken, not in the interests of a

true Union, but of this Jacobin faction. . .Their reconstruction

measures, in their sense of them, were an entire success,— and did just

what they designed,— helped them to elect a series of Jacobin

Presidents and to fix their parties and policy upon the country. True:

those measures placed the noblest white race on earth beneath the heels

of a foul minority constructed of a horde of black, semi-barbarous

ex-slaves and a gang of white plunderers and renegades."

(Discussions by Robert L. Dabney, Volume IV, The True

Purpose of the Civil War, p. 106).

Dabney kept stirring the pot throughout the post-war years, agitating

always againist Black equality. When followers of Dabney talk about "Jacobins" and the French Revolution, they are talking about measures like "negro suffrage," which

they oppose. "And now that every hope of the existence of Church, and of State, and of civilization itself, hangs upon our arduous effort to defeat the doctrine of negro suffrage, shall the General Assembly be invoked, to go out of its province, and stretch its constitution, so as to set the most significant precedent which can he imagined, in favour of this destructive doctrine?"

(Robert Lewis Dabney, 1867, Against the

Ecclesiastical Equality of Negro Preachers in our Church, and their

Right to Rule over White Christians). These grievances were only magnified through Reconstruction

and beyond and are at this point unappeasable and irremediable.

Malum in Se Malum in Se

P.T. Barnum used to say there's a sucker born every minute. Realizing

that people are wonderfully impressed by an ethical argument with Latin

phrases sprinkled throughout, Robert Lewis Dabney gives us 'malum per

se,' a Latin phrase meaning 'evil in itself.' Slavery, he explains,

cannot be 'evil in itself,' because the word occurs in the Old

Testament, in some cases, without condemnation, as when provision is

made for the slave who wants to remain attached to his master; he does

not want to go free in the Jubilee. In that case, "He shall also bring

him to the door, or to the doorpost, and his master shall pierce his

ear with an awl; and he shall serve him forever."

(Exodus 21:6).

Malum in se is a phrase heard in legal theory that refers to

those things which are wrong in themselves, not wrong by convention. For

instance, stopping your car when you see an octagonal red sign that says

'Stop' is a social convention. It's not inherently wrong to blow

by such a sign, though the law may attach penalties to so doing. But

identifying theft and murder as wrong is not a convention; rather, these

are things which ought to be everywhere criminal; if they are not, there

is something seriously wrong with the law code. Robert Lewis Dabney,

Moscow Idaho's favorite unreconstructed Confederate, used to use the

principle in his arguments in defense of slavery, purporting to show

that, while local law codes might attach a penalty to owning saves if

such was the pleasure of the legislature, owning slaves cannot be wrong

in itself.

Now, how would we know if a thing is wrong in itself? Why, if God

decrees it, for any reason, at any time, under any circumstances,

then it cannot be wrong in itself. Surely you would not accuse the

Judge of all the earth of wrong-doing! Anything God commands must be

inherently innocent and righteous. And does God include captivity

and slavery in His list of judicial punishments that He may, at His

discretion, apply to mankind? Yes, He does. See, for example, the

blessings and curses attached to the law, in Deuteronomy 28,

"And there you shall be offered for sale to our enemies as male and female saves, but no one will buy you."

(Deuteronomy 28:18)

What could be more plain? The Lord intends to reduce to servitude those who defy Him;

He Himself says as much. So therefore any Virginia plantation-owner

who does the same, who reduces a man to servitude for his own

convenience, is only doing what God does and such a thing cannot be

wrong in itself, malum in se. Attached to this is some confused

notion that God's punishments must, in the end, be remedial; yet

blotting a people out from under the sky cannot be remedial in any

sense. What is left to remediate?

Now if you are Doug Wilson, you start back in astonishment at the

brilliance of this argument, and imagine that all the abolitionists

who faced Robert Lewis Dabney on the debate stage in the lead-up to

the Civil War came away abashed, looking downward in confusion, too

ashamed to meet R.L.'s commanding gaze. Well, maybe that never

actually happened, but he did write a letter to the editor. And not

only is this not a brilliant argument in defense of slavery or

anything else, it's one of the worst arguments ever advanced with a

straight face in defense of anything.

And you will hear similar arguments over and over again from Moscow, Idaho,

who have generalized the principle behind it to be an all-purpose

get-out-of-jail-free card. Whenever there is a clear divine command to

do this or do that, they look over, behind, and around it, to find

instances of people who did not obey that command (maybe because it

had not yet been delivered). If any such instance can be found, even

a single, solitary case, then, in their mind, that eradicates the

command. It's excised right straight out of the Bible, just like

Thomas Jefferson excised problem texts out of his copy of the New

Testament. Does the New Testament say the saints are not to use filthy language? It

does. Oh, but the prophets do! Are you saying God did something

wrong? The argument might be summarized as 'If God can do it, we can

do it.' The concept, it's not wrong for Him, but it is wrong for

you, is beyond their capacity to formulate. Are you saying the rules

are different for Him than for you? That's not fair! The rules must

be the same for all.

|