|

You will sometimes hear it stated that no one in the ancient world

found any moral problem with slavery. This is very far from

being the truth. Not only the Christian Circumcelliones, but pagans

writers, did perceive moral dilemmas associated with slavery. Alcidamas of

Elaea, of the school of Gorgias, left behind a bon mot which unfortunately

survives only in fragmentary state: "God has left all men free; nature has

made no one a slave."

The Stoic Epictetus, himself a slave, spoke movingly about his

condition:

"But when you have asked for warm water and the slave has not heard, or if he did hear has brought only tepid water, or he is not even found to be in the house, then not to be vexed or to burst with passion, is not this acceptable to the gods? How then shall a man endure such persons as this slave? Slave yourself, will you not bear with your own brother, who has Zeus for his progenitor, and is like a son from the same seeds and of the same descent from above? But if you have been put in any such higher place, will you immediately make yourself a tyrant? Will you not remember who you are, and whom you rule? that they are kinsmen, that they are brethren by nature, that they are the offspring of Zeus? But I have purchased them, and they have not purchased me. Do you see in what direction you are looking, that it is toward the earth, toward the pit, that it is toward these wretched laws of dead men? but toward the laws of the gods you are not looking."

(Epictetus, Discourses, Book I, Chapter 13).

The Stoics were not abolitionists; they were not looking for

political reform of the slavery system, rather, they sought to solve

the problem, of how can our minds remain free while our bodies are

under the control of others. A recondite moral problem perhaps, but

not one which proceeds from the premise that slavery is entirely

unproblematical morally. Epictetus himself had been a slave. He is not

the Frederick Douglass of his people, but neither is he any great

booster of the slavery system. In a sort of delayed reaction, his teaching

would later prove an inspiration for the Haitian liberator, Toussaint

L'Overture.

Dio Chrysostom does not regard the slavery system as morally

justifiable, realizing that it all hangs on the question of whether the

conqueror can legitimately enslave the populace of the defeated town:

"For manifestly of those who from time to time acquire slaves, as they acquire all other pieces of property, some get them from others either as a free gift from someone or by inheritance or by purchase, whereas some few from the very beginning have possession of those who were born under their roof, 'home-bred' slaves as they call them. A third method of acquiring possession is when a man takes a prisoner in war or even in brigandage and in this way holds the man after enslaving him, the oldest method of all, I presume. For it is not likely that the first men to become slaves were born of slaves in the first place, but that they were overpowered in brigandage or war and thus compelled to be slaves to their captors. So we see that this earliest method, upon which all the others depend, is exceedingly vulnerable and has no validity at all; for just as soon as those men are able to make their escape, there is nothing to prevent them from being free as having been in servitude unjustly. Consequently, they were not slaves before that, either. And sometimes they not only escaped from slavery themselves, but also reduced their masters to slavery. In this case, also, we have now found that 'at the flip of a shell,' as the saying goes, their positions are completely reversed."

(Dio Chrysostom, Fifteenth Discourse).

To be sure, Dio was no abolitionist. Indeed, he has the chutzpah to

complain when his own slaves ran away owing to the ups and downs of his

affairs: ". . .so many slaves had run away and obtained freedom, so many persons had defrauded me of money, so many were occupying lands of mine, since there was no one to prevent such doings."

(Dio Chrysostom, Discourse 45, 10). But to claim, as they do, that he

and his contemporaries perceived no moral problem at all in slavery is

simply fanciful. They understood that the institution which was the

cornerstone of their economy was, morally, deeply problematical.

At the close of every year, the Roman

people celebrated the Saturnalia, in honor of King Saturn, a legendary

ruler in Italy with some imagined connection to the planet of the same

name. The observance, which unfortunately generally degenerated into a

drunken riot, looked back to the Golden Age believed to have existed,

before there was war, before there was slavery, when people lived on

acorns. "They established a holiday on which masters and slaves should eat together,— not as the only day for this custom, but as obligatory on that day in any case."

(Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Letter 47). Masters waited upon

their slaves. This, again, was not a practical program for abolition,

but neither was it an unvarnished endorsement of the existing system.

Everyone knew, and was reminded by the recurring Saturnalia, that life

could be different.

When slave liberations did occur, as under Moses or Solon the

Athenian, the liberators did not liberate all slaves for all time nor

intend to do so. Slaves were freed, but there was no 13th amendment

to follow in a mopping up operation. Solon intended to free those Athenian

citizens who had fallen into slavery owing to debt, not foreigners. This he

did:

"But most agree that it was the taking off the debts

that was called Seisacthea, which is confirmed by some places in his

poem, where he takes honor to himself, that

"'The mortgage-stones that covered her, by me

Removed,— the land that was slave is free;'

"that some who had been seized for their debts he had brought back from

other countries, where

"'— so far their lot to roam,

They had forgot the language of their

home;'

"and some he had set at liberty,—

"'Who here in shameful servitude were held.'"

(Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans, Life of Solon).

Cyrus the Persian was another partial liberator. A cylinder is still

extant in which, in the second part, Cyrus speaks in the first person. He begins with his titles and continues saying that he took care of Marduk's cult at Babylon, and that he had “allowed them to find rest from their exhaustion, their servitude.”

(The Cyrus Cylinder, World History Encyclopedia). These individuals

may have personally been in a state of servitude, or the community as a

whole may have been placed in a disadvantageous state, which he rectified,

and fully expected to feel their gratitude. This partial character of

ancient emancipations reflects, I think the birth of slavery in war. Or so

Heraclitus thought:

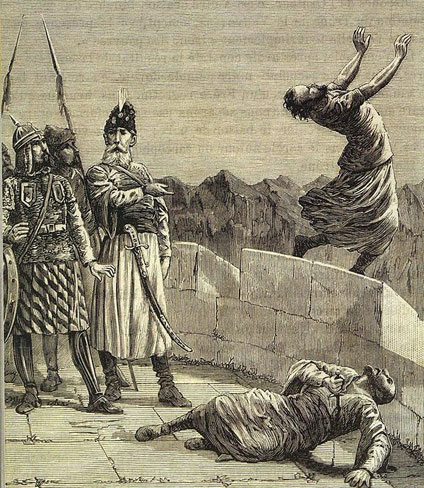

“Polemos (War) is the father of all beings, and the king of all beings: some of them he turns into

gods, and others into humans, some he makes slaves, and others makes free.”

(Fr. 32L / B 53, Heraclitus).

It does seem that Heraclitus is on to something in thinking that war is

the progenitor of slavery as an institution. And in war, there are winners

and losers; it is the ultimate zero sum game. When Adolf Hitler invaded

Yugoslavia, he did not cosy up to the Serbs, who were already the dominant

group. Rather, he portrayed himself as the liberator of the Croats, who

had been second-class citizens in their own native land. Certainly war can

lead to a reversal of fortune, where oppressed and oppressor change

places. The rematch, if held, would then be a

war of liberation for the slaves, though not necessarily animated by any

principled opposition to slavery.

|