|

These

people are in grievous error to think that this is where our form of

government comes from. Did the French Revolution invent democracy,

free speech, abolitionism, as they claim? The fact of the matter is that

the French Revolutionists did not know what to do with Haiti; Napoleon tried

to take it back. The tendency broadly known as the Enlightenment

included in its ranks Christians, and also people who thought of themselves as

Christian though their theology was sketchy, like John Locke and Thomas

Jefferson, as well as Deists, and atheists. There was no Chinese wall surrounding

Christian political thought, and a dense interconnecting web ties up some of these

loose ends, for example abolitionist Josiah Wedgwood belonged to

the Enlightenment Lunar Society. These

people are in grievous error to think that this is where our form of

government comes from. Did the French Revolution invent democracy,

free speech, abolitionism, as they claim? The fact of the matter is that

the French Revolutionists did not know what to do with Haiti; Napoleon tried

to take it back. The tendency broadly known as the Enlightenment

included in its ranks Christians, and also people who thought of themselves as

Christian though their theology was sketchy, like John Locke and Thomas

Jefferson, as well as Deists, and atheists. There was no Chinese wall surrounding

Christian political thought, and a dense interconnecting web ties up some of these

loose ends, for example abolitionist Josiah Wedgwood belonged to

the Enlightenment Lunar Society.

The truth is that anyone at all can share

in the admiration of the stunning scientific achievements of that era while

continuing to dispute about the doctrinal consequences of those new

discoveries. If gravitation somehow makes Christianity unthinkable, why was

its discoverer a Christian (though unfortunately not an orthodox one)? Nevertheless Marxist historians have sold

themselves and others a bill of goods in trying to find abolitionism in

an author like Voltaire, who believed in polygenesis and invested his

money in slave-trading. The energy for abolition was coming

from the Christian side, from groups like the Quakers though not only

the Quakers.

Those old enough to recall the Cold War will remember that the

rivalry between the United States and Russia extended even to rival

claims of precedence in inventing things. The Russians claimed that they

had invented the telephone, the internal combustion engine, and even the

game of baseball. In a similar vein, the atheists

tell us that, although they are few in number, they are the

movers and shakers behind human history. Thus they concur with Confederate

partisans like Robert Lewis Dabney that it is they who are really behind

this nation's heritage of freedom, democracy, and religious liberty —

that they were the first to discover that these were good things, and

established them in the teeth of universal

religious opposition. Thus these two counter-cultural, minority religious streams converge. Douglas Wilson and his ideological

descendants inherited their historical paradigm from Robert Lewis Dabney, and proceed to 'prove' it

by pointing to the atheists who think the same way. One hand washes the

other.

The trouble is, it is really hard

to make this derivation stick historically. Americans viewed the French Revolution at

first with sympathy, then with bewilderment, and finally with horror. It

was productive of nothing, certainly not on this side of the Atlantic, and

not only because it's tough to make the time-line run backwards. Where you

do see religious liberty in the world today, why trace it back to the

French Revolution rather than, say, to Jan Hus, or even back to

Tertullian and Lactantius? The French Revolution neither preached nor

practiced it, and to this day the French do not enjoy liberty of

conscience; instead they have 'secularism,' which means the government

is free to issue edicts banning, for instance, the Islamic head-scarf,

though such edicts serve no public purpose. But Dabney said democracy

comes out of the French Revolution, and so they believe. Then,

having stuck a fictitious and implausible derivation onto freedom and democracy, the

Muscovites proceed to invoke the genetic fallacy: because American liberty's

origin is so questionable, the thing itself must be rejected. This is

the methodology known as 'Presuppositionalism.'

A wide variety of views on politics and society were expressed within the era that

modestly called itself the 'Enlightenment.' If Marxist

historians want to skim off all the good and assign it to Enlightenment

rationalists, leaving what's left to revanchist Christians, this is not

an objective procedure. The French Revolution, which instituted an

idolatrous cult of reason and persecuted those who would not bow the

knee to it, is not where we get freedom of religion from. They never

even had it, nor understood it! What Americans celebrate as good: democracy,

liberty, free speech, religious freedom — the Neoconfederates are convinced are

bad things, wicked, evil, rebellion against God, which must be eliminated before America can be classed as a

Christian nation. Everything we love, they hate.

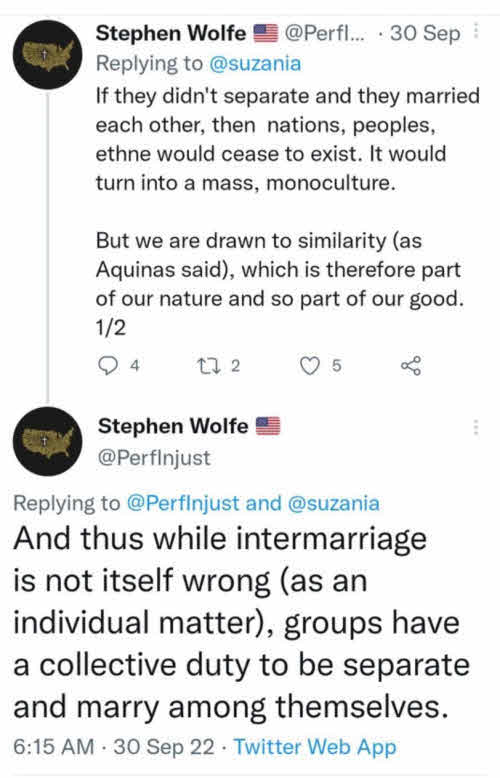

Meanwhile, if you are looking for a political ideology which really

was forged in the Enlightenment, not having existed previously, look no

further than nationalism, which these folks have thoughtfully repackaged

for resale. When Herder discovered that people could only be really free

if governed by those who spoke the same native language, this was indeed

a new discovery, nothing comparable having been known to antiquity.

Thus this political philosophy, as with other Enlightenment

discoveries, has both good and bad points. For the old empires to break

up and their component parts embark upon self-government is an advance

according to the principle of subsidiarity: the idea that policy ought

to be handled by the level of government in closest contact with the

people governed. But nationalism has, alas, has also proved itself to be

a war-generating machine. The logic of why an Enlightenment-invented

theory, like nationalism, is good, while other ideas with an ancient

pedigree, like freedom and democracy, which were championed by some

Enlightenment authors, are discredited by that very association, is not

developed by this faction.

Some of the time they hear of, or they themselves discover the Christian roots of our

polity. Then they argue the opposite case with all the industry of a

man sawing off the limb upon which he is sitting. Who believes that our

liberties flow from the French Revolution? They do, as do atheist

historians looking for comfort and support, not the rest of us. We have

nothing invested in this shaky theory. Or will they adopt, for the

moment, the contrary view, that Christians invented those things? What sense

then can we make of their

argument, 'Christians invented freedom and democracy, so therefore we

must discard those things?' If they are good things, if they are

Christian things, we should cherish them. Thus, some of the time, we learn

from them that religious toleration is a cultural product of

"Anglo-Protestantism." If so, why do they want to get rid of it?

This entire effort to subordinate Christianity to some imagined

'Anglo-Saxon' culture that existed somewhere, some time, ought to excite

suspicion in itself. Never mind that, according to the U.S. Census, there

are fewer self-described people of Anglo-Saxon ethnicity in this country

than German-Americans, or Irish Americans, to say nothing of Hispanics. The

description of (some) inhabitants of the British Isles as 'Anglo-Saxon'

seems to have been invented in the first place to differentiate the

English from the Irish, with whom they were locked in a death struggle

for centuries, finally culminating in the Irish winning autonomy for

Ireland, excepting the northern counties. The Romans knew Ireland was

there, but never conquered it, and early abandoned Britain north of

Hadrian's wall. The Anglo-Saxon invaders never knew Ireland was there,

or so it is said, and never made any effort to conquer the place. Like

most conquerors, they contributed their DNA to the surviving population,

yet fell short of total population replacement. How to say British

without giving a brotherly nod to the hated Irish? Say, Anglo-Saxon. Some

people, at least, who live in England are Anglo-Saxon; certainly more so

than in this country: "In England, the average citizen is 37% British,

with a smaller Irish heritage of 20%." (The Belfast

Telegraph, 'Genetic Map Reveals how British, Irish and European we

Actually Are,' Allan Preston, July 29, 2016).

As they point out, the United States owes much culturally to England,

the mother country. Legal precedents from the British common law

tradition carry weight that no foreign law ever could; we speak English;

students read British literature in school, not the Brothers Karamazov.

When I listen to them, I start to wonder if I am the only person who was

made to read Ralph Waldo Emerson's essay, 'The American Scholar,' in

school. He says,

"Is it not the chief disgrace in the world, not to be a

unit;— not to be reckoned one character;— not to yield that

peculiar fruit which each man was created to bear, but to be reckoned

in the gross, in the hundred, or the thousand, of the party, the

section, to which we belong; and our opinion predicted geographically,

as the north, or the south? Not so, brothers and friends,— please God,

ours shall not be so. We will walk on our own feet; we will work with

our own hands; we will speak our own minds." (Ralph Waldo Emerson, The

American Scholar).

Not being a Ralph Waldo Emerson fan, I gave the matter no further

thought until, hearing these people, the recollection awakened in me

that, no, American literature is not a tiny rivulet in the great stream

of Anglo-Saxon culture. It is sui generis, a new thing, because a great

and mighty continent cannot be made to bow before a little island. But

in the minds of some people, we do not hold the Bible in our hands and

read it unfiltered; the Bible itself has somehow been taken captive by

the Anglo-Saxons, pagans though they were when they conquered Britain, crafty pirates indeed: "Well, I will, perhaps, just to

set some issues before us here, what I feel in common immediately with

you is that I start with the biblical inheritance and my conservatism

also immediately gets to the fact that it is within, in my case, a

Protestant frame and an Anglo inheritance that is very much a British

inheritance." (Al Mohler, Thinking in Public, A

Conversation with Yoram Hazony). So to these good folks, we inherited the Bible from. . .Great Britain.

Only, not the Irish part. I've heard of British Israelitism before, which is

when you do the Black Hebrew Israelite thing, only with Anglo-Saxons.

When you read the Bible, you must hear it through the pinched accents of

a bewigged Anglican clergyman. Like, would it make sense otherwise?

The Bible exhorts us "today," "Today, if you will hear His voice: 'Do

not harden your hearts, as in the rebellion, as in the day of trial in

the wilderness. . .'" (Psalm 95:7-8). Whose

today? Moses'? David's? Our own? The Bible says, today means today, you

had to ask?: ". . .but exhort one another daily, while it is called

'Today,' lest any of you be hardened through the deceitfulness of sin."

(Hebrews 3:13). The Bible, you could say, is

timeless. So if you want access to the Bible and evaluate that as a

positive thing, why assume only certain esoteric historical portals are

available to access it? Is it Calvinism? Is it the idea that this

ideology went as far as it could go in the century beyond John Calvin,

and can only decline thereafter; so if you want to know what the Bible

says, you should study the minor Calvinists of the seventeenth century?

Is it post-modernism? Are we assuming the intent of the author is

inaccessible to us? Al Mohler is no figure of the lunatic fringe, but he

takes a similar approach to our current author: if you want to know what

the Bible says, read someone who lived millennia later and thousands of

miles away. Who would know the Bible like the Anglo-Protestants?

The charismatics would say, you could talk it over with the Author.

But say it not out loud. The Bible testifies of itself that it is not so

hard to unravel: "For this commandment which I command you today is not

too mysterious for you, nor is it far off. It is not in heaven, that you

should say, 'Who will ascend into heaven for us and bring it to us, that

we may hear it and do it?' Nor is it beyond the sea, that you should

say, 'Who will go over the sea for us and bring it to us, that we may

hear it and do it?' But the word is very near you, in your mouth and in

your heart, that you may do it." (Deuteronomy

30:11-13). It seems if you are looking for second-hand religion,

faith at one remove, you need look no further than the Calvinists. But

why outsource the task? If we must relegate the Bible to human history

at all, and look for it, not up, but disappearing in the rear-view

mirror, isn't first century Palestine a better resting place and

depository than seventeenth century England? Why does seventeenth

century England come into the conversation at all?

We are told that religious toleration is an Anglo-Saxon thing, not,

say, a North African thing. Never mind that England is the very country from which the Puritans had to flee

in order to find liberty to worship according to their own lights, and never mind that Maryland,

founded as a haven for persecuted Catholics, initially enjoyed more

religious liberty than did Puritan New England. The American founding fathers expressed themselves with a wonderful

clarity. Efforts to define down what they meant, either by foreign

neofascists like Yoram Hazony or domestic authors, cannot convince any

who have read their words. They said what they meant and they meant what

they said. Moreover, they were right.

Theonomy Theonomy

Theonomists believe that the law of Moses was intended to be a

universal law, applicable at all times and places to all people. Our author

denies this: "I deny, however, that the civil laws in the Mosaic law are immutable and universally applicable."

(Wolfe, Stephen. The Case for Christian Nationalism (p. 270).) Our

author does not believe in universal law: “A people need the strength, resolve, and spirit to enact their own laws, and they should not seek some universal

'blueprint' they can rubber-stamp into law.” (Wolfe,

Stephen. The Case for Christian Nationalism (p. 264).) He explains

that Mosaic law is one possible instance of law: ". . .it is one possible body of law.

. . But it is not thereby a suitable body of law for all nations." (Wolfe, Stephen. The Case for Christian Nationalism (pp. 265-266).)

It is strange that our author's efforts to market his magnum opus

brought him to Moscow, Idaho, because the view that there should be one,

singular universal code of law is not really a popular viewpoint

nowadays, if indeed it ever was. It is a program without a constituency.

There is, however, one group in the world today that wants to impose a

uniform law code across all continents, peoples, climes, and languages,

and that is the theonomists. Doug Wilson's cult are, or were thought to

be, sometimes adherents of theonomy.

You might expect the theonomists would not much like this author, because he does

not believe what they believe. But no. Some of them, at least, love him. Who knows why: because

he owns the libs, maybe? There is no consistent adherence to any set of

principles here. Is there some agenda behind this manifest inconsistency, or

is this strictly one of those cults where, when you

join, you must leave your brain in the jar by the door, and bite your tongue

when the leadership wanders around in circles? You cannot be both

for and also against universality in the law. A drive toward universality

cannot be both the besetting sin of Western modernity and also the

most noteworthy, and controversial, characteristic of your 'conservative' allies. Our author perceives

the desire for a universal code of law, such as Mosaic law would be

under the theonomists' interpretation, to represent a "retreat to

universality," which has something to do with 'the West:'

"Supplying a set of laws, in my judgment, only feeds into the tendency of Westerners to retreat to universality, whereby people look for something outside themselves to order themselves concretely." (Wolfe, Stephen. The Case for Christian Nationalism (p. 264). Canon Press. Kindle Edition.)

This idea of the Mosaic law as a universal law code isn't new. This

tendency to 'universalize' which he decries, can't be laid at the door

of modernity, much less of any 'post-war consensus.' The Judaizers

Paul encountered seem to have had a similar idea. I would have to agree

with our author, however, that this concept of a 'one-size-fits-all' law

code is not well thought out. Nations are differently circumstanced and have

different needs.

What's the 'or else' in this author's stark manifesto? National

suicide: ". . .ultimately your people will self-immolate in national suicide."

(Wolfe, Stephen. The Case for Christian Nationalism

(p. 172).) We'll be 'replaced,' you see. Our author most

emphatically is not a conservative, any more than is his mentor. To be fair,

our author cannot be blamed that people try to mischaracterize his

posse in this way; he admits, accurately: “We are not 'conservative,' nor are we

'traditionalist.'” (Wolfe, Stephen. The Case for Christian Nationalism (p. 38).)

Conservatives, in the American tradition, are people who believe in the

Constitution, not people who want to shred it.

Honesty is a rare virtue in

people of this tendency. During the Trump era, we have grown accustomed

to hearing the repetition of lies so transparent no one could possibly

believe them — like that Antifa did 1/6. Statements of this kind

serve more in the way animals mark their territory than as anything that

might be believed to have actually happened. So you do see people

on Twitter who insist that a.) they are conservatives, and the people

who disagree with them are 'Leftists;' b.) they agree with Stephen Wolfe,

and c.) they uphold the Constitution, unlike some other parties who are

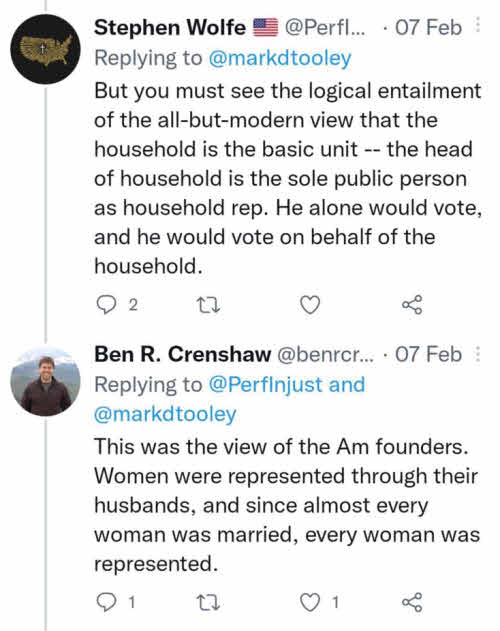

imagined to despise the Constitution. But at a minimum, Mr. Wolfe's

program involves shredding out of the Constitution the First Amendment,

the Fourteenth Amendment, and the 19th Amendment. The 'no religious

test' clause will have to go as well, because ". . .positive affirmations of doctrine can be conditions for civil office or for outsiders who seek residence, since these are voluntary actions."

(Wolfe, Stephen. The Case for Christian Nationalism

(p. 396).) When these people say that they support the

Constitution, they mean no more than that there is theoretically some

Constitution which they might be willing to uphold, though they want to

see the downfall of the existing one with its guarantee of religious

liberty. Better if they honestly say, 'we are not conservatives, nor are we

patriots.'

Like the Bohemian Corporal of

a bygone era, our author is a disgruntled military veteran. He

notes, ominously: ". . .the prospects of continued domestic peace in the future is becoming unlikely." (Wolfe, Stephen. The Case for Christian Nationalism

(p. 322).) According to these people, revolution is justified because we are under occupation:

"Christian Americans should see themselves as under a sort of occupation.

. .The ruling class is hostile to your Christian town, to your Christian people, and to your Christian heritage."

(Wolfe, Stephen. The Case for Christian

Nationalism (p. 344).).

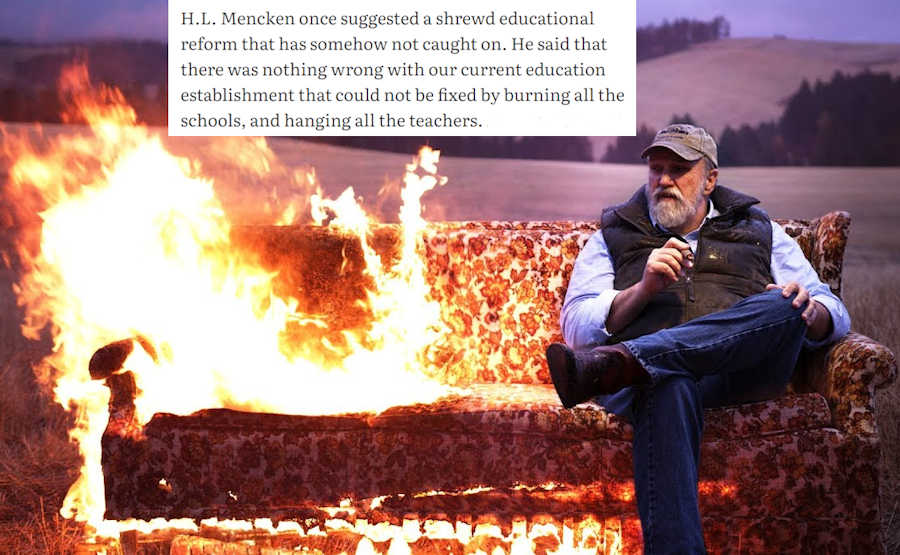

As noted, Mr. Wolfe's' book is published by Canon Press, the family-owned vanity publishing house

of Douglas Wilson, who has been making terroristic threats of this nature

for quite some time:

|