Wrath of Achilles

An author faces an unrepeated opportunity, in the opening lines

of a book, for laying out his topic to a reader whose attention will never

be more sharply focused. This is why the first word of

Homer's Iliad is "wrath:" because the book is about the wrath of

Achilles. This works well for authors whose thought process is

organized and consecutive. Now on to our author, who begins his tome with a

complaint about Albanian life:

"The people of Albania have a venerable tradition of

vendetta called Kanun: if a man commits a murder, his victim's family can kill any one of his male relatives in reprisal. . .Untold

numbers of Albanian men and boys live as prisoners of their homes

even now." (Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape, p. 1).

Readers who loyally forge onward, expecting these Albanians to

turn up again, do not appreciate how scatter-brained an author we

are accompanying. These disappearing Albanians remind the reader of the

old saw about the phone book: lots of interesting characters are

introduced, but never developed in any depth.

Our author's tunnel vision allows him to see only the evil in

usages not of his own time and place. His readers have encountered this

cultural narcissism before: this man's whole aim in life is to look

at others and say, 'I'm better than you.' This boast is his

'ethics,' if you please. Clan justice, where there are

no law courts or police nor any means of obtaining those things, is

not an unmixed evil, but the only deterrence against a sky-rocketing

murder rate. Certainly law is a step upward, though these Albanians

do not see it. Blood vengeance, which is usually carried out by the next of

kin against a murderer and not his entire family as is reported

here, is a little like the policy of Mutual Assured Destruction

which kept the peace during the Cold War: it is a great system of

deterrence so long as it deters, but should deterrence fail, it is

the road to disaster. Once a murder is committed, violence spreads

out in ever-widening ripples: the victim's brother kills the

murderer, whose next-of-kin then kills the avenging brother, whose

relatives then kill the murderer's next-of-kin who killed the

avenging brother, until the entire tribe is depopulated; like a rock

rolling downhill, the process cannot stop. It makes no exception for

'justice' nor even for 'accident.' The process can and has, however,

been stopped, though this will require a detour through religion.

So what is to be done with our Albanians? What did decades of officially atheistic government do to eradicate this practice?

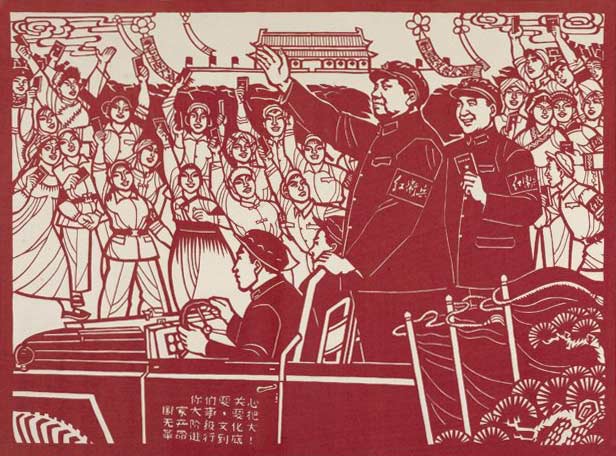

Though untold Albanians were confined as virtual "prisoners in their

homes" expected to listen to their "Great Teacher," leather-lunged

Dictator Enver Hoxha, deliver his lengthy atheist rants, this

evidently did nothing to change their behavior. If the isolationist

Albanians are not an atheist success story, then who is? Atheism failed.

Contrast the case of the Waodani tribe of South America. No noble savages these, murder

was the principal cause of death for their tribe before they heard

the gospel. When five missionaries landed their plane to share the

gospel, true to form, they murdered them. Yet the survivors stayed,

and taught the Waodani that God's word said, "Dearly beloved, avenge

not yourselves, but rather give place unto wrath: for it is written,

Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord." (Romans 12:19). As

described in the documentary "Beyond the Gates of Splendor," the

murder rate plummeted as the Waodani took God's proclaimed monopoly on

vengeance to heart.

One might expect it is 'scientific' to go with what works, but

some people think it's much more 'scientific' to go with what demonstrably does not work.

Our author never thinks to take up the path of friendly persuasion

blazed by the surviving missionaries; he does not want to talk the

Albanians nor the Afghans into doing what he thinks they should be

doing instead of what they are now doing. He prefers the path of

coercion; he is a great enthusiast for the U.S. military remaking local society.

In his utopia, freedom from foreign rule is not a positive value. But Enver Hoxha could have told him

how well it works out to use the police power of the state to crush

religion. Ultimately coercing people into adopting atheism is futile.

Flash-Light

There was a TV advertisement some years ago, showing a Soviet

'fashion show,' featuring a heavy-set babushka wearing a shapeless

sack of a dress. Then a sign appeared advertising 'evening wear:'

the same babushka came back out, wearing the same shapeless sack,

this time carrying a flash-light. The trouble with atheist lives is

that they have no plot. People do not dance in the streets all day

because they have "hot showers"; the atheists have forgotten that

man does not live by bread alone. The people Sam Harris despises would never

trade his inner life for theirs, because they have a horror of a vacuum.

Unmet Expectations

Sam Harris' readers expect of something of him. Alas, he cannot quite grasp what

it is they want. They say things like this:

"The most common objection to my argument is some

version of the following:

"But you haven't said why the well-being of conscious

beings ought to matter to us. If someone wants to torture all

conscious beings to the point of madness, what is to say that he

isn't just as 'moral' as you are?

"While I do not think anyone sincerely believes that this

kind of moral skepticism makes sense, there is no shortage of

people who will press this point with a ferocity that often passes

for sincerity."

(Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape, p. 32)

At some level, Sam Harris realizes that these people do

not themselves believe torturing all conscious beings to the point of

madness is virtuous conduct, nor are they indifferent to virtue. His hearers are leaning forward

in their chairs, gesturing with an encouraging hand, as if to say,

'go on.' They are waiting for him to deliver the groceries. You see,

this is what we expect from a toiler in the vineyard of ethics: he

should explain to us why we should do what he says we should do.

That is the whole point of the endeavor.

Not only can Sam Harris not deliver the goods, he really can't

even understand what it is these people want of him. Our author

noodles along, sharing his likes and dislikes as if he were on

Facebook, delivering the occasional laugh line or sound-bite. He is altogether innocent of

what a well-constructed argument might look like. By his own report,

the mis-match between our author and his philosophical audience is complete;

what they expect, he cannot deliver. When asked the obvious, inescapable

questions with which any ethical system will be met, his response is

plain puzzlement, a blank stare: Why on earth would you ask that?

He opens his heart to us so that we can see how vivid, fiery,

incandescent and pure are his hatreds; he is a

professional hater, not an ethicist. But if, even after glimpsing

how vividly Sam Harris hates the Taliban, the Catholic Church, evangelical

Christians, Albanians or whomever, his listener is not moved to adopt his

hatreds as her own, he in the end can only walk away: "I found that I could not utter another word to her."

(Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape, p. 44). Our junior apprentice ethicist

is not the garrulous type, like Socrates, who was always ready to talk to

anybody. Dialectic is not what he gives us, only personal likes and dislikes.

In lieu of offering his readers a reason why they should

adopt his ideas of right and wrong, our author is reduced to making noises of disgust

and astonishment, demeaning his unconvinced readers as moral

skeptics or moral relativists, though himself aware the greater

number are not, nor are they likely to throw battery acid in the face of

a child; he is erecting a straw-man. Instead of setting out to

revolutionize ethics, a better plan would have been for our author

to sit down and familiarize himself with prior offerings in the

field; that way he at least would have had some idea of what it is

these people expect, and he would not be left with no options but body language.

Fallacy of Scale

So far as I know 'fallacy of scale' is a neologism; people don't make this mistake often

enough for the term to be needed. But enter Sam Harris, with

his by now familiar illogic. I mean by 'fallacy of

scale' the error of assuming that, because I can bring down a

house consisting of six over-lapping cards by blowing on it, it is

therefore very likely I can also bring down a full-size brick

house by blowing on it.

As we've seen, Sam Harris has already 'argued' in favor of his

postulate of human interdependence by proposing two

hypothetical cases, the Maximal Misery Universe and the Maximal

Happiness Universe, both of which had the odd characteristic, ex

hypothesi, that we all suffer misery together or we all flourish

together. But this characteristic, if it is claimed as a feature of

the real world, must be shown to be such, not trucked in stuck to an

unexamined packing crate. Here again we have an effort to prove interdependence, 'we are all in this together,' with

similar success.

People sometimes say, 'I wouldn't date him if he were the only

other person left on earth.' Most people do not 'hear' this

catch-phrase as meaning the same as, 'I wouldn't date him if he were

one of three billion available persons on earth,' because there is

something different about being one of only two persons dwelling

upon the earth. We can afford to be choosy with three billion options,

but there is a powerful incentive to learn to get along with even an

annoying person, who is your only hope of human companionship, or

indeed of leaving behind children to continue the depopulated human

race. Not many have ever experienced the lonely prospect of being

'the last of the Mohicans,' the last of one's kind, but it cannot be

an encouraging feeling.

Sam Harris points out that it would have been

ill-advised for Adam and Eve to smash a rock into each other's face.

Doing so would have reduced their prospects for happiness in a

direct and immediate way. Two people, if they are the only two people on

earth, need each other. To our author's way of thinking, there cannot be any difference

between this case and a quarrelling couple amongst six billions:

"Why would the difference between right and wrong answers suddenly

disappear once we add 6.7 billion more people to this experiment?"

(Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape, p. 41). The short answer is,

because a tsunami can carry away hundreds of thousands without

affecting our immediate personal prospects for happiness (don't be afflicted

with mourning or regret, dear reader; the Utilitarian system only values

conscious existence, which by their count rules out dead folk. What exactly is

wrong with a quick, painless death is difficult for Utilitarianism to say.).

If Adam and Eve can sort amongst three billion prospective mates,

divorce is not quite the disaster it would have been in the Garden.

Scale does matter. Again, competent ethicists have

argued in favor of human inter-dependence; but for this to be a

rational ethics rather than a catalog of Sam Harris' personal likes

and dislikes, we must await a non-fallacious argument showing this to be so.

Hall of Mirrors

Recall the Utilitarian founder Jeremy Bentham set up the standard of general happiness

as the definition of right and wrong, the sole standard to be applied in determining whether an act

was moral or immoral. Sam Harris' 'Moral Landscape' is already a

heterogeneous place, a junk-yard filled with pleasure and pain,

hot showers, crime and punishment, this and that. Sam Harris was

reminded that many people rejected Jeremy Bentham's innovation

because, when put to the test, this sole criterion produced

results unacceptable to the older morality: for instance, if a

large group of people enslaved a smaller group and thrived on their

uncompensated toil down in the diamond mines, this might

well produce greater good for the greater number, but could

never be just. At this they frowned, and suffered discomfort.

So a light bulb flashed on in Sam Harris' mind: all

this injustice proliferating under the Utilitarian system is

making people uncomfortable. And that is just what is wrong

with it! Let's add 'a preference for right over wrong' to our list of things that

promote well-being: hot showers, good nutrition, and enough

justice to make people smile. Now the 'moral landscape' is

populated with hot showers, good nutrition, law and order, and

not only that, but morality, too. See:

"Fairness is not merely an abstract principle—it is a felt

experience. . .It seems perfectly reasonable, within a consequentialist

framework, for each of us to submit to a system of justice in which our immediate, selfish interests will often by superseded by considerations of fairness."

(Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape, pp. 79-80).

How are we now defining "justice"? No longer in Utilitarian

terms. As in the old movies where an amorphous blob shuddered through

the movie theatre, agglomerating to itself the seats, the carpeting,

the slower patrons, and all that lies before it, Sam Harris'

"well-being" has agglomerated to itself the old standard of

traditional morality,— or at least as much of that stuff as our resident

"moral expert" is prepared to tolerate,— and now, at long last, the

people rejoice, Utilitarianism has been fixed.

But this brilliant move of atheist logic carries a price. You see

it is not as helpful as it might seem to define things in terms of

themselves. It sets up a rotary motion, and once you hop on that

merry-go-round and whirl around a few times, even the atheist will

begin to feel queasy with motion-sickness. We have defined right and wrong

as follows,

- Right and wrong are defined as what promotes well-being, and

- Well-being is defined as, among other things, satisfying a preference

for right over wrong, by those so disposed.

From 2.) we rush back to 1.) to find out what "right and wrong" are, but can never quite catch up to ourselves.

This self-referential definition is circular to the second degree,

because not all moral concerns are moral, our author intones: ". . .many

people's moral concerns must be immoral." (Sam Harris, The Moral

Landscape, p. 87). So first we must employ a definition of morality

other than well-being to weed out the immoral morals, then we require

another as we add satisfaction of the remnant moral concerns to

'well-being,' then we redefine morality to mean 'well-being, including

the satisfaction of some, but not all, moral concerns'!

Pretty Pebble

As he goes noodling along, offering us his insights into morals and the good life, our author decides to adopt

a reductive, materialistic approach to brain function. It is a pretty pebble laying on the ground, so

why not pick it up? That this approach leaves no room for free will, our author understands,

intoning: "The illusion of free will is itself an illusion."

(Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape, p. 112.)

Recall this is the author who has earlier said,

"If only one person in the world held down a terrified, struggling,

screaming little girl, cut off her genitals with a septic blade, and sewed her back up,

. . .the only question would be how severely that person should be punished,

and whether the death penalty would be a sufficiently severe sanction."

(Donald Symons, quoted with apparent approval by Sam Harris, The Moral

Landscape, p. 46).

This censorious, moralizing approach is the one he takes to condemn religious-motivated

people, because he erroneously assumes female circumcision arises through religious motives.

(Or could it be that these people correctly understand that: perhaps

the real target in their sights is male circumcision, an undeniably religious

practice, the sign of the covenant,— and they hope to succeed where

Emperor Hadrian failed?) Sam Harris does realize that the pretty pebble he has picked

up, reductive materialism, leaves no room for moral censoriousness:

"But it seems quite clear that a retributive impulse, based upon the

idea that each person is the free author of his thoughts and actions,

rests on a cognitive and emotional illusion—and perpetuates a

moral one." (Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape, p. 111). What was that,

again, about "whether the death penalty would be a sufficiently severe

sanction?" He sententiously explains, "The men and women on death row

have some combination of bad genes, bad parents, bad ideas, and bad

luck—which of these quantities, exactly, were they responsible

for?" (Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape, p. 109). Does that

include those he wants to see on death row for female circumcision?

One cannot help but throw up one's hands in hopeless astonishment

at these 'New Atheists.' Have these people never heard that a is not

not-a? Will someone please explain to Sam Harris that he cannot set

up shop as a censorious moralist if he also believes free will is an

illusion?

Lest anyone think this man is an isolated case, someone whose bad

genes or bad luck prevented him from ever learning logic, look at

Richard Dawkins, who breathlessly blurbs on this author's book

jacket: "'The Moral Landscape' has changed all that for me."

(Richard Dawkins, The Moral Landscape, back cover). Richard Dawkins,

who used to call abstract ideas 'memes' which jumped from host to

host, rewiring and reorganizing their hosts' neural structures as their own needs

required, now buys into the idea of self-moved neurons, no longer the helpless, parasitized host

of active and creative thought, but rather themselves the prime movers. Self-starting neuronal storms kick up apparent 'memes,'

deceptively similar to 'memes' in other brains, yet they cannot

really be the same when we understand "the mind as the product of

the physical brain." (Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape, p. 110). This

is a new thing: a host that creates and controls its own parasite!

|