|

True to their French Revolutionary heritage, the Khmer Rouge banned all religions; they were equal-opportunity persecutors, murdering

Buddhist monks alongside Vietnamese Christians. The sanguinary Democratic Kampuchea National

Anthem sets the tone:

"Bright red blood covers the towns and plains

of Kampuchea, our Motherland,

Sublime blood of the workers and peasants,

Sublime blood of the revolutionary men and women fighters!

The blood changes into unrelenting hatred

And resolute struggle. . ."

(quoted

p. 248, 'Pol Pot, Anatomy of a Nightmare,' Philip Short).

The most distinctive act of this new regime, the emptying out of the

cities, is not canonical Marxism. It was a pragmatic measure

already in use before the fall of Phnom Penh. The Khmer Rouge had found

that the towns they 'liberated' kept falling back into their

bad old habits; just as soon as they stamped out the black market, it

sprang back up again: "But the private sector remained active: 'Kratie

township showed the same signs as in the old society. Honda motorcycles

were speeding up and down the streets like before, while our ragged

guerrillas walked in the dust. This showed that they were still the

masters.'" (The Pol Pot Regime, Ben Kiernan, p. 62). In the cities, people found a way to live their

lives in the interstices of the socialist system, not under complete

party control as were the peasants in the village communes. And above all they

wanted control; this enlightened, atheist system was one of universal

slavery:

"What Pol and his colleagues approved that spring was a

slave state, the first in modern times. . . Pol enslaved the Cambodian

people literally, by incarcerating them within a social and

political structure, a 'prison without walls,' as refugees would

later call it, where they were required to execute without payment

whatever work was assigned to them for as long as the cadres ordered

it, failing which they risked punishment ranging from the

withholding of rations to death. Food and clothing were, in theory,

provided by the state. But there were no wages." (p. 291, Pol Pot,

The Anatomy of a Nightmare, Philip Short.)

So they began the policy of forced evacuation of 'liberated'

cities and towns; what they did to Phnom Penh was already established policy. They

taught their troops that cities were evil: "'The city is bad because

there is money in the city,' a Khmer Rouge cadre told Ponchaud.

'People can be reformed, but not cities.'" (p. 279, Pol Pot, The

Anatomy of a Nightmare, Philip Short). Twenty thousand people

perished in the evacuation of Phnom Penh, a forced march into the

country-side that set even the sick and maimed in motion:

"It was a stupefying sight, a human flood pouring out of

the city, some people pushing their cars, others with overladen

motorcycles or bicycles overflowing with bundles, and others behind

little home-made carts. Most were on foot. . . ." (Eye-witness

account, quoted p. 272, Pol Pot, Anatomy of a Nightmare, by Philip

Short).

The ground where these millions of people travelled on their march to

the jungle was littered with discarded refrigerators, sewing machines, clothing, and dead

bodies. There, in the Year Zero, they began to make the world anew, with no

infrastructure, no schools, clinics or food stores awaiting them. Mao Zedong had already defined the ideology of a peasant

revolution, where the peasants, not the (non-existent) urban

proletariat, were the revolutionary class. Like other atheist

world-makers, Mao wanted a blank slate, a clean piece of paper on

which to paint his master-piece: "'Poor people want change, want

revolution. A clean sheet of paper has no blotches, and so the

purest and most beautiful words can be written on it.'"

(Mao Zedong,

quoted p. 148, Pol Pot, Anatomy of a Nightmare, Philip Short.)

Unfortunately people as they were let these atheist dreamers down,

and so they had to kill a lot of them. In addition to the starvation which

always accompanies a Great Leap Forward in the country-side,

they simply did away with a lot of these people:

"'Those we surprised at night in the act of saying bad

things, we educated, which means that they worked harder than the

others. If they repeated the offence, they were killed with a cudgel

or a pickaxe. Then they were buried and that was that.'"

(Young village militiaman, quoted p. 322, Pol Pot, Anatomy of a Nightmare,

by Philip Short).

The Khmer Rouge gave the world the sparkling slogan, "'To spare you

is no profit, to destroy you is no loss.'" (John Withington, Disaster!,

p. 239). Without irony, the leadership urged the survivors to emulate the condition of oxen:

"'You see the ox, comrades. Admire him! He eats where we [tell]

him to eat. . .When we tell him to pull the plow, he pulls it.'"

(p. 309, Pol Pot, Anatomy of a Nightmare, by Philip Short). Along with cities, they dispensed with money:

"Mok favored a barter system. . .He also said if there

were no money, it would remove the problem of corruption and curtail

the activities of enemy agents. 'When a wound is not yet healed,' he

said, 'you shouldn't push a stick into it. You must leave it alone,

otherwise it will get worse.'" (p. 307, Pol Pot, Anatomy of at

Nightmare, Philip Short).

"'Zero for him, zero for you — that is communism,'

Khieu Sampan had said." (p. 317, Pol Pot, Anatomy of a Nightmare,

Philip Short).

Under their new constitution, religion was abolished, so the Buddhist monasteries

were emptied out. Strangely enough, in spite of their hostility

to Buddhism and other indigenous religions including Islam, the Khmer Rouge had internalized the Buddhist

directive of eliminating the human personality: "The ultimate goal

for a Khmer Rouge was 'to have no personality at all.'"

(p. 318, Pol Pot, Anatomy of a Nightmare, by Philip Short). The Buddhist ideal of 'no

mind' seeks to silence the internal dialogue which goes along with

the human condition. Foreign visitors to Cambodia during these years

noticed the robotic, emotionless affect of the survivors, though

some of this may have been the lassitude accompanying

near-starvation.

The surviving inhabitants of Cambodia spent the

Khmer Rouge years engaging in self-criticism, writing

auto-biographies, and seeking to eliminate such vestiges of the old

way of thinking as saying 'I:' "Language was stripped bare of

incorrect allusions. Instead of 'I,' people had to say 'we.'"

(p. 324, Pol Pot, Anatomy of a Nightmare, by Philip Short). Readers of Bolshevik

refugee Ayn Rand will recall that she predicted this, as expressed on

the title page of 'Anthem:'

"They existed only to serve the State. . .From cradle to

grave, the crowd was one—the great We.

"In all that was

left of humanity there was only one man who dared to think, seek

and love. He, Equality 7-2521, came close to losing his life

because his knowledge was regarded as treacherous blasphemy. .

.he had rediscovered the lost and holy word—I."

(Ayn Rand, Anthem, Title Page.)

"In some parts of the country, it was forbidden even to laugh or sing."

(p. 328, Pol Pot, Anatomy of a Nightmare, by Philip Short).

Starvation raced with political repression to see which could

kill more Cambodians. In the end the two joined hands, forming a

death vortex. Rural socialism produced a famine, as it always does. Prohibition of foraging as leading to

'individualism' and introduction of mandatory communal dining worsened the food

shortage. Pol Pot was not willing to tolerate dissent; non-conformists were enemies to be liquidated:

"In a broadcast on Radio Phnom Penh, Pol surmised that

'between 1 and 2 per cent of the population' was irredeemably

hostile and 'must be dealt with as we would any enemy'. . ."

(p. 368, Pol Pot, The Anatomy of a Nightmare, Philip Short.)

Testimony of anti-government conspiracy was obtained by the C.I.A.'s

own favored mode of torture, simulated drowning. Torture worked its

magic and yielded signed confessions. Further evidence that enemies

roamed amongst the people of Cambodia was the very fact that they were

starving: "'Hidden enemies seek to deprive the people of food,' he [Pol]

told the Central Committee in December 1976." (p. 369, Pol Pot, the

Anatomy of a Nightmare, Philip Short). Enemies of the state were

liquidated; that the people were starving showed these enemies' power

and activity, and so murder raced with famine to see which could claim

more lives. So intense was the Khmer Rouges' passion for secrecy and

their aversion to transparency that, even as thousands were losing their lives to this atheist

regime, the rank-and-file Cambodians did not know they were being

governed by a man named Pol Pot, nor that Pol Pot was Saloth Sar, nor

that the country was being governed by the Cambodian Communist Party;

these mysteries were revealed only gradually.

Like many other atheist regimes, they had a special hatred for

the religious. Though Cambodia was a French colony as was Vietnam,

French missionaries were less successful in converting the

Cambodians to Catholicism. More than 80 per cent of the population

in 1975, the year Zero, was Buddhist. A

minority group, the Cham, practiced Islam, and some small tribes in the

mountains practiced indigenous folk religions. The Pol Pot years were dangerous ones for

Buddhist monks and the religious minorities. After Phnom Penh fell,

the Buddhist monks were ordered out of their monasteries and into

the fields to grow rice. These plans were laid out in a May of 1975:

"Ret said that 'eleven points' were discussed, but his

colleagues, interviewed in 1980, could recall his mentioning only

the leadership's orders to 'kill Lon Nol soldiers, kill the monks,

[and] expel the Vietnamese population' and its opposition to 'money,

schools and hospitals.'" (The Pol Pot Regime, Ben Kiernan, p. 56).

'Kill' is a harsh word, and perhaps it was not used:

"Heng Samrin, then studying military affairs under Son

Sen, was also at the meeting. He recalls the use of yet another

term: 'They did not say "kill," they said "scatter the people of the

old government." Scatter them away, don't allow them to remain in

the framework. [...]

"On the other hand, Samrin adds: 'Monks, they said, were

to be disbanded, put aside as a "special class," the most important

to fight. They had to be wiped out. . .I heard Pol Pot say this

myself. . .He said no monks were to be allowed, no festivals were to

be allowed any more, meaning "wipe out religion."'"

(The Pol Pot Regime, Ben Kiernan, p. 57).

By September of 1975 the government felt they had nearly met their goal:

"Buddhist monks 'have disappeared from 90 to 95

percent,' the rest being 'nothing to worry about.'" (The Pol Pot

Regime, Ben Kiernan, p. 100).

Many of these Buddhist monks had been killed, though guilty of no crime,

and the survivors had been terrified into silence. Monks were on the hit

list: "'In 1977, they started killing capitalists, students, monks,

and even Chinese and Vietnamese, even if they could speak Cambodian.

These classes were killed by being beaten to death with poles.'"

(The Pol Pot Regime, Ben Kiernan, p. 291).

Adherents of minority religions, such as the Muslim Cham people, likewise suffered persecution:

"As the White Scarves waited in the neighboring province

for a response from Samphan, D[emocratic] K[ampuchea] officials

banned Islam, closed the local mosque, and dispersed the Cham

population as far as the northwest provinces. Some Muslims were

forced to eat pork, on pain of death. . .The officials

began killing any who infringed these regulations. One local peasant

recalls: 'Some Cham villages completed disappeared; only two or

three people remained.'" (The Pol Pot Regime, Ben Kiernan, p. 2.)

The Khmer Rouge systematically murdered the Islamic leadership:

"They gave these details for the most prominent Cham

victims: Imam Haji Res Los, Cambodia's Grand Mufti, was thrown into

boiling water and then struck on the head with an iron bar, at

Konhom, Peam Chisor, Prey Veng, on 8 October 1975; Haji Suleiman

Shoukri, the 1st Mufti, was beaten to death and thrown into a ditch,

at Kahe, Prek Angchanh, Kandal, in August 1975; Haji Mat Sles

Suleiman, the 2nd Mufti, was tortured and disembowelled in

Battambang, on 10 August 1975; Haji Mat Ly Harum, Chairman of

Cambodia's Islamic Association, died of starvation in prison at

Anlong Sen, Kandal, on 25 September 1975. . ." (The Pol Pot Regime,

Ben Kiernan, p. 271.)

This leadership hunt went on down to the merest 'hajji,' any person

who had made the pilgrimage to Mecca. The Khmer Rouge confiscated the

Koran: "In June or July 1975, Ly asserts, the Krauchhmar authorities

attempted to collect all copies of the Koran there, and obliged Cham

girls to cut their hair." (The Pol Pot Regime, Ben Kiernan, p. 263.)

Once communal dining was introduced, there was no way for Muslims to

conceal their disinclination for eating pork, which could be lethal: "In

her group of five Cham families in Kantuot village, there was one death

from illness, and in other villages, at least four Chams were killed for

refusing to eat pork. 'They were accused of being holy men in the old

society,' she says." (The Pol Pot Regime, Ben Kiernan, p. 283.) This

population group, whose ancestors came to Cambodia from India, was

dispersed, their villages broken up, and suffered heavy casualties:

"Imam Him Mathot told him that he had been evacuated

from Phnom Penh to Kompong Speu with five hundred Cham families,

totalling about three thousand people. Fewer than seven hundred

survived in 1979, according to the Imam: 'Half the deaths were due

to starvation, and the other half by execution.'" (The Pol Pot

Regime, Ben Kiernan, p. 285.)

With the Khmer Rouge, the 'or else' was often immediate execution: 'What if

I don't want to leave Phnom Penh?' 'Bang.' So it was with those not

happy to see their religion banned. When people nowadays talk like Pol

Pot, Sam Harris for example, there is no empirical historical reason to

think they don't mean just exactly what they say. According to the

common law adage, "the Devil himself knows not the thoughts of man"; the

Khmer Rouge could not wipe out inward devotion, but they did wipe out

every outward expression of religion, from the Buddhism which once

dominated Cambodian culture to the animism of the mountain tribes who early

came under communist domination:

"On Bun Phan, an ethnic Lao then

serving in the Voeunsai district militia, recalls that starting from

about 1971, the CPK [Cambodian Communist Party] 'collected all the

people into one place,' ending their dispersed, semi-nomadic way of

life. . .'And religion was made to disappear completely. Anyone who

believed in it was killed.' Lao were affected by the destruction of

Buddhist wats, but animist shrines were also targeted. 'From 1970

they came and propagandized the people not to believe in anything at

all. They wiped it all out. . .Pol Pot personally spoke about wiping

out religion.'" (The Pol Pot Regime, Ben Kiernan, pp. 82-83).

The nearly four years of the Pol Pot regime can serve as a test case for the

proposition that 'religion poisons everything.' The Khmer Rouge did

away with religion. After that, were the skies bright, was life

wonderful? No, life was a nightmare: "'My mother had never seen my

children, but she did not dare approach us until the village chief and

militia had left. . .She said to survive, you had to do three things.

. .know nothing, hear nothing, see nothing.'" (The Pol Pot Regime, Ben

Kiernan, p. 170). But above all you must be happy; the atheists frown if

your frozen smile clenches: "'And anyone they suspected of not being

happy with them, they killed.'" (The Pol Pot Regime, Ben Kiernan, p.

185.)

Enver Hoxha

This atheist intellectual decided to bring about the utopia envisioned by John Lennon's song, 'Imagine,'

and rid the world of faith. To do that, of course, you have to kill a lot of people.

By his own confession, this man hated God:

"Whoever has read 'Prometheus' will remember the

words of the hero to Hermes, the servant of the gods:

"'Be sure, I would never want to exchange my miserable fate for

your servitude, because I would rather be bound with chains to

this rock than be the obedient lackey of Zeus...

"'In a

word, I hate all Gods.

"Marx said:

"'Prometheus

is the noblest saint and martyr in the philosophical calendar.'"

(Enver Hoxha, Literature and Art Should Serve to

Temper People with Class Consciousness for the Construction of

Socialism: The closing

speech delivered at the 15th Plenum of the CC of the PLA.)

Prometheus, who stole fire from the pagan gods to give to man, was a favorite Marxist hero.

They could whole-heartedly second the sentiments the play-wright placed

in their hero's mouth, "I hate all Gods."

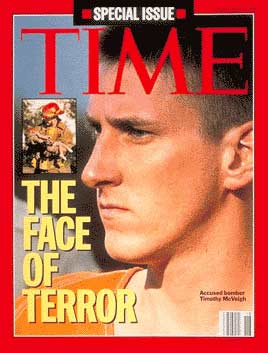

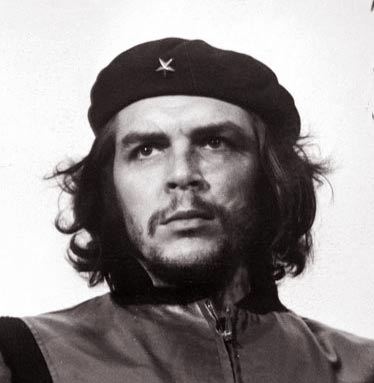

Che Guevara

You used to see this man's face on people's tee-shirts:

|