It is said,

"But I say unto you, Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you;

that ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust."

(Matthew 5:44-45).

"But love your enemies, do good, and lend, hoping

for nothing in return; and your reward will be great, and you will

be sons of the Most High. For He is kind to the unthankful and

evil. Therefore be merciful, just as your Father

also is merciful." (Luke 6:35-36).

If we are imitating God when we love our enemies, then it stands to

reason that He loves the sinner. We all know people we love intensely whom we wish would get with the program. 'Hatred' is not, to us, the

immediate and inevitable consequence of awareness of defect. Thus we hear, 'Hate the sin, love the sinner.' However sound that advice may be

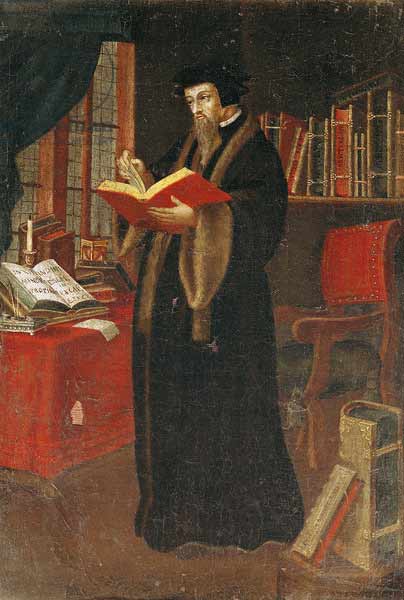

for finite sinners to follow, the Bible does in several places confirm John Calvin's perception that God

holds the person of the sinner in detestation along with his sin: "For thou art not a God

that hath pleasure in wickedness: neither shall evil dwell with

thee. The foolish shall not stand in thy sight: thou hatest all

workers of iniquity. Thou shalt destroy them that speak leasing: the

LORD will abhor the bloody and deceitful man." (Psalm 5:4-6). God is

perfectly holy, and cannot abide evil: "Thou art of

purer eyes than to behold evil, and canst not look on iniquity:

wherefore lookest thou upon them that deal treacherously, and

holdest thy tongue when the wicked devoureth the man that is more

righteous than he?" (Habakkuk 1:13). Psalm 11 confirms the

principle that God abhors the sinner: "The LORD is in his holy temple,

the LORD’S throne is in heaven: his eyes behold, his eyelids try, the

children of men. The LORD trieth the righteous: but the wicked and him

that loveth violence his soul hateth." (Psalm 11:4-5). We know that the Bible

also says, "But God commendeth his love toward us, in that, while we

were yet sinners, Christ died for us." (Romans 5:8); but what God loves

in the sinner is not his sin, which disfigures him and renders him

hideous and unlovely.

What the Bible does not confirm, however, is John Calvin's

principle that God hates all sinners equally. This is the

foundation-stone of his system; since all sinners are equally

obnoxious in His sight, He can have no possible basis for preferring

one above another and saving those He loves; He hates them

all...equally. But does the Bible ever say that God hates all

people, equally? Or does it explicitly trace out divine sympathies

and exclusions? Is the Bible actually a very long book tracing out these

themes, redundantly even?

Jesus "loved" the rich young ruler: "Then Jesus, looking at him,

loved him, and said to him. . ." (Mark 10:21). Yet this young man did

not follow the Lord, at least not at that time. That there is a loved

person, who is yet lost, disproves the system. The system requires that

the Lord never be disappointed in love, and look, with tear-stained

eyes, after a wayward one marching to Hell.

To summarize Calvin's argument, it runs like so:

- God cares about nothing in human beings but merit. Every

human disposition, thought, or action may be classified as

meritorious. . .or marked with a demerit. This is the legacy of

a thousand years of medieval scholastic legalism.

- God perceives no merit in unregenerate sinners because they

have none; recall, the exaggerated form of the Bible doctrine of

human depravity leaves them all in equal condition; they are

wicked in each particular, good in none. Thus each is in a

perfectly equal circumstance, since 0=0.

- Like the donkey suspended forever between two equidistant

bales of hay, God will not act unless given a motive. All

available bales of hay, all the sinners for whom Jesus died, are

equally distant, equally worthless, therefore God can have no basis in His

foreknowledge of any quality belonging to these bales to move.

- Therefore, since He can have no possible basis for choosing

one sinner above another, He will remain motionless forever, as (they said)

the donkey would do. Yet we know that He acts. He acts, therefore, solely for reasons

limited to within His own sphere, to vindicate His own free sovereignty, with no regard to

any foreknown characteristic of the sinner, selected or overlooked, in picking out the

jewels for His kingdom. There is no foreknown characteristic of the elect

which can have any possible relevance to their election.

In response, there is no evidence that God cares about nothing in human beings but moral

merit, of which admittedly we have none, except for what is on loan from Him.

Nor is it entirely clear that all are in equal failure, as the system

requires: "He has mercy upon one and not on another, according to his

own good pleasure, because all are equally unworthy and guilty." (Charles

Hodge, Systematic Theology, Kindle location 17736). Certainly all have failed,

nor does God grade on a curve. He is a physician who heals the sick, not the

whole: "This is a faithful saying and worthy of all acceptance,

that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am

chief." (1 Timothy 1:15). What is breath-taking about the Calvinist

scheme, however, is its total impersonality. This scheme presents

a God who is a heavenly Mr. Magoo, too near-sighted to tell any of his

creatures apart. It cannot be ruled out that there are actual human

characteristics of which He takes notice.

This man-made system requires all sinners to be equal, not

approximately (as they are, by comparison with God), but precisely, by

comparison with one another. Notice that this Calvinist speaker cannot

allow some sinners to have been more oppressive than the norm, because

such an inequality would upset the delicate balance upon which rests, in

their eyes, God's freedom: "Let me make it clear. In God's eyes, listen,

no one is a victim! We are all perpetrators of open rebellion,

scandalous, blasphemous sin against God." (John MacArthur, Social

Justice and the Gospel, Part 1, Grace to You, 42:14-42:49). Get it? If

some sinners were less flagrant than others, this would introduce

inequality and thus bring in a possible factual basis for God's choice:

He could choose the lesser sinners! Now we know He does not so choose;

if anything, He chooses the more flagrant. This 'principle,' that "no

one is a victim," is identified as "the critical, fundamental principle

of the gospel"! One must suppose that, in the Calvinist Bible, when the

children of Israel cried out against Pharaoh's oppression, they heard,

"Shut up," He explained. "They are no worse than you." Now, it's true

that they are not, but that is not how these cases are decided. That

this posited equality simply isn't so we can see very clearly, in the

Bible as well as by common sense, where sinners are ranked, are surely

and confidently as in Dante's Inferno:

"Woe unto thee, Chorazin! woe unto thee, Bethsaida! for if the mighty works, which were done in you, had been done in Tyre and Sidon, they would have repented long ago in sackcloth and ashes.

But I say unto you, It shall be more tolerable for Tyre and Sidon at the day of judgment, than for you.

And thou, Capernaum, which art exalted unto heaven, shalt be brought down to hell: for if the mighty works, which have been done in thee, had been done in Sodom, it would have remained until this day."

(Matthew 11:21-23, see also Matthew 12:41-42).

Moreover, we all know is our own experience grounds for preferring one

person above another which are unrelated to merit. For example, why do we value our own friends? Perhaps because she has a

lovely singing voice, and he has a rollicking sense of humor. But who could imagine that the gates of heaven are barred to

the tone-deaf, or to people who need to have the punch-line explained to them? These are not meritorious qualities,

only entertaining ones. Certainly God, unlike us, stands in no need of being entertained. Yet He has indicated, in His

word, that there are human qualities which interest Him, beyond merit. When someone suffers a gross injustice,

when a child is snatched off the sidewalk and brutally murdered, everyone feels for the victim family, even if under

other circumstances there would be no special reason to champion or

celebrate this family. God, it would seem, is not immune from this tug of sympathy on His heart; He

is with the oppressed, and against the oppressors, though there is

nothing meritorious in suffering oppression. He sides with some people,

and against others, out of sympathy.

In response, I would note there is no evidence that God cares

about nothing in human beings but moral merit, of which admittedly

we have none, except for what is on loan from Him. We all know in

our own experience grounds for preferring one person above another

which are unrelated to merit. For example, why do we value our own

friends? Perhaps because she has a lovely singing voice, and he has

a rollicking sense of humor. But who could imagine that the gates of

heaven are barred to the tone-deaf, or to people who need to have

the punch-line explained to them? These are not meritorious

qualities, only entertaining ones. Certainly God, unlike us, stands

in no need of being entertained. Yet He has indicated, in His word,

that there are human qualities which interest Him, beyond merit.

When someone suffers a gross injustice, when a child is snatched off

the sidewalk and brutally murdered, everyone feels for the victim

family, even if under other circumstances there would be no special

reason to champion or celebrate this particular family. God, it

would seem, feels the very same way; He is with the oppressed, and

against the oppressors, though there is nothing meritorious in

suffering oppression. He sides with some people, and against others,

because He feels the tug of sympathy. Though we cannot, with our finite minds, ever trace

out the balance of motives in God's choice of a particular saint,

surely there is no sense in discarding all that the Bible says, very

plainly and succinctly, about God choosing the poor over the rich,

the little over the mighty; He says this is what He is doing, why

not believe Him? John Calvin's idea, that He only says this to show

that there is no reason for what He is doing, is simply to put one's

fingers in one's ears and to silence the voice of God.

Restricting God's world of concern to merit and nothing but merit is

arbitrary and unbiblical. Admittedly, moral merit comes only from God. If God chose His elect on the

basis of merit, He would be choosing His saints based on His own gifts

to them, an entirely circular proceeding. However it goes much too far

to say, if He does not choose on the basis of merit, He chooses on the

basis of nothing. A thousand years of scholasticism redefined almost

everything human as meritorious or non-meritorious, including several

features which are plainly placed outside that realm by the Bible

itself. 'Faith,' to take one example, is a meritorious work by

scholastic standards, but not classed as such by the Bible. To be sure,

non-meritorious as it is, it is a gift of God, but it should be plain to

the observer that these categories have gotten skewed, with the

'merit/demerit' category growing especially bloated.

The Calvinist system is so impersonal

that no one can be left with the impression that God loves him personally. He

hates everything about us. He wills to love what He will make of us, once

He has obliterated what we are, but perhaps even this will be a poor piece

of work, because John Calvin was very weak on the

positive side of Christian life, sanctification. There is nothing that

anybody can say to God which will interest Him or make Him care. To be sure in

Calvinism He saves His elect, yet He handles them with tongs. One cannot confirm this construct by

Bible study. Though many of His friends have been scalawags and low-lifes,

men like Jacob, Abraham, and David, there does seem to be something

in these men that He cherishes, just as we love our friends. To take

'love' at something like its ordinary meaning is enough to demolish

this system, because in Calvinism, God's only object of love is

Himself: all God loves in His saints are their merits, which He supplies.

This cannot be confirmed from the Bible, which leaves open the

possibility that perhaps there is something else that He loves also.

This agenda of equalization is very much at the heart of the

Calvinist system. Because every sinner totally depraved, every

sinner is equal to every other sinner, all weighing in at a round

zero. So God cannot act in accordance with the rubric that the sick need a

physician, not the healthy, and gather the more sinful ones to himself,

because John Calvin has made them all to be equally sinful. Because none is rich compared with God, we are all equally poor in

His sight, so the oft-expressed Bible principle that He loves the

poor applies equally to everyone, or no one. This tendency toward

equalization ought to excite the reader's suspicion, because the

Bible does not make distinctions for no reason. Why is

John Calvin continually levelling these carefully wrought distinctions, so

that in the end he can assure us that God chooses His elect for no

reason at all? God comforts those who mourn, and as John Calvin reminds

us we all ought to mourn over our sins, but some people mourn more than

others, say if they have lost their family in a tsunami. Every one of

these Bible disparities and distinctions John Calvin levels and equalizes,

though in context they function as distinctions and disparities: it is a

given that not everyone is in the same boat with regard to these

qualifiers. There is something wrong here.

Two merchants met at a train station, so the old story says. One

asks the other, 'Where are you going?' 'To Minsk,' he replies. His

competitor shouts, 'Aha! You say you are going to Minsk because you

want me to think you're going to Pinsk! But,— you crafty old

liar,— I happen to know you really are going to Minsk!' Here a man

told the truth, but in the distrustful environment in which he found

himself, he was not believed. God speaks at great length in the

Bible about which people He chooses for His own: the poor, the weak,

the oppressed. But in John Calvin's eyes, that appears to be such a

preposterous basis for a salvation plan that God cannot be taken

seriously when He advances it; rather, He tells us that He chooses

the small over the mighty to impress upon us that, in reality, He

chooses people for no reason at all; after all, we are all small in

proportion to God. So that, like the travelling salesman's itinerary, God's

answer is simply not believed, but is taken as evidence for a completely

different answer. But suppose He really is going to Minsk?

Over-Generalization

In leading the Hebrew slaves out of slavery in Egypt, God 'hardened Pharaoh's heart:'

"And I will harden Pharaoh’s heart, and multiply My signs and My wonders in the land of Egypt."

(Exodus 7:3).

What does this mean? That God intends to put steel

for Pharaoh's paste-board. Pharaoh is disposed to be vacillating and

weak-kneed; God intends to make him bold and resolute enough

to stand up to Moses. If there is no contest, there is no victory. Boldness

and resolution are normally perceived as positive things, but a wicked

man who is bold and resolute is more trouble to the world than a wicked man

who is cowardly; however, God intends a public demonstration, which will not happen if

Pharaoh wimps out. But the Calvinist interpretation is that God

is making a good man wicked! He was already wicked.

The Calvinist explains, that if God turns the king's heart, as He

certainly does: "The king’s heart is in the hand of the Lord,

like the rivers of water; He turns it wherever He wishes."

(Proverbs 21:1). . .then so He must turn the commoner's heart; if He

stiffened Pharaoh's wavering resolve, then so He does to every

sinner without exception. But God's word speaks of how He abandons those who

have become entrenched in their rebellion against Him: " For this cause

God gave them up unto vile affections: for even their women did change

the natural use into that which is against nature. . ."

(Romans 1:26).

There is no new-born child in this condition, bearing any such

well-founded judgment against himself: "So I gave them up unto their own

hearts’ lust: and they walked in their own counsels."

(Psalm 81:12). It

is certain that this divine abandonment leaves these obdurate sinners in

a state of free-fall, but this judgment cannot be extended to the entire

human race, severed from reference to where these people took their

stand. We are not all Pharaoh.

It is legitimate to search out principles, based on induction,

from instances on record in the Bible. It is not legitimate to

ignore counter-examples and pronounce general principles founded

upon one instance, or several instances if these represent a sequestered part of the evidence, not the

balanced whole. God hardened Pharaoh's heart, but He did nothing to

suggest to the child-sacrificers the horror which they perpetrated:

"And they built the high places of Baal, which are in the valley of

the son of Hinnom, to cause their sons and their daughters to pass

through the fire unto Molech; which I commanded them not, neither

came it into my mind, that they should do this abomination, to cause

Judah to sin." (Jeremiah 32:35). This abomination did not come into God's mind.

Why is the case of Pharaoh, if indeed even that case can be understood in

their sense, to be taken as the general rule, rather than the case of the self-starting Molech-worshippers?

Another instance is Hosea 8:4:

"They set up kings, but not by Me; they made princes, but I did not acknowledge them. From their silver and gold They made idols for themselves—

that they might be cut off."

(Hosea 8:4).

God is saying, this wickedness does not come from Him, it is not His contribution to the world; and it

is strange indeed that the Calvinists insist that it is:

"God's eternal purpose as to evil acts of free agents is

more than barely permissive; His prescience of it is more than a

scientia media of what is, to Him, contingent. It is a determinate

purpose achieved in providence by means efficient, and to Him,

certain in their influence on free agents." (Robert Lewis Dabney,

Systematic Theology, Chapter 21, Kindle location 8241).

Their analysis leaves only one free agent in the cosmos: God; and so He must commit

not only all good, but also all evil. Perish the thought! God is not

tempted, and does not tempt: "Let no man say when he is tempted, I

am tempted of God: for God cannot be tempted with evil, neither

tempteth he any man: But every man is tempted, when he is drawn away

of his own lust, and enticed." (James 1:13-14).

The Calvinist might object, it is not they who are importing God's

just sentence against Pharaoh into alien contexts, but Paul, who raises this

case in Romans 9. Paul, therefore, must think Pharaoh's case is exactly

like our own. But this is not the way Paul's argument works. The rabbinic reasoning in which Paul

was trained leaned heavily toward a fortiori argumentation, or what the

Rabbis termed heavy and light. This is a form of argument by analogy, as

if one would say, 'if stealing a woman's pocket-book is wrong, how much

worse is robbing a bank.' For instance, there is no explicit mention in the Mosaic law

of bank robbery, nor were there any bankers in attendance when the law

came down at Sinai; still, robbing banks is not legal under Moses' law,

as any practitioner of this form of reasoning could readily demonstrate.

The cases do not need to be identical for the analogy to hold: robbing a

bank is not exactly like rustling sheep, but it is close enough; in

fact, it's worse. Paul is not, in fact, saying that the cases he brings up are exactly alike, nor

that each of them forms part of our own experience.

Classical logic viewed argument by analogy with suspicion, as an

inherently weak form of argumentation. Thus those trained in classical

logic tend to assume that Paul would not have brought up any comparison

cases unless the analogy were perfect, unless they were in all respects

just like the index case. That is how you get Calvinism out of Romans 9.

But rabbinic reasoning tends to trust argument by analogy, as being the

precise instrument to accomplish its limited goal of determining whether

novel behavior is legal or illegal under Moses' code. How else would you

make that determination? In what respects

are Paul's analogies like, and in what unlike? His diagnosis of the

rebellious Jewish leaders who rejected Jesus as Messiah is as follows:

". . .but Israel, pursuing the law of righteousness, has not attained to the law of righteousness. Why? Because they did not seek it by faith, but as it were, by the works of the law."

(Romans 9:31-32). Now was this Esau's problem, that he sought

righteousness by works? We have no reason so to believe. Was it

Pharaoh's problem? Of course not! His problem was contempt for the

living God, a problem not shared by the first century Jewish leadership

at all. The cases are not identical. They are the same at the juncture

of comparison, that none of these people has any grounds to complain

against God. But Paul says the cases are identical. No, he does not.

Adam's Free-Will

John Calvin knew it would be heretical to deny Adam's free-will,

and so he did not: "We admit that man's condition while he still

remained upright was such that he could incline to either side."

(John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book II, Chapter

III, Section 10). His successors, however, felt free to deny any

possibility of human freedom, for anyone, at any time. If no human

being has ever been free, then Adam was not free, contradicting John

Calvin's teaching on this point. John Calvin was admittedly weak in

seconding the Bible promise that the saints will regain their lost freedom,

but he adequately repeats the Bible teaching on Adam. The Bible teaches

that man was made upright: "Lo, this only have I found, that God hath

made man upright; but they have sought out many inventions."

(Ecclesiastes 7:29). Adam was not unfree before the fall, but only after.

Modern Calvinists' efforts to find some feature in the fabric of

time, eternity, and foreknowledge that obliterates the possibility

of human freedom must come to terms with John Calvin's own teaching

that there was one man who was free, Adam: "They perversely search

out God's handwork in their own pollution, when the ought rather to

have sought it in that unimpaired and uncorrupted nature of Adam.

Our destruction, therefore, comes from the guilt of our flesh, not

from God, inasmuch as we have perished solely because we have

degenerated from our original condition." (John Calvin, Institutes

of the Christian Religion, Book II, Chapter I, Section 10). God

created Adam good, and free; that is man's "original condition." How could He have done this, if

creaturely freedom is a metaphysical impossibility?

That Adam's children retain some measure of freedom, or have it

restored by the new birth, is apparent in such Biblical plaints as, "I

have spread out my hands all the day unto a rebellious people, which

walketh in a way that was not good, after their own thoughts;. . ."

(Isaiah 65:2). It is not very convincing to recast this divine lament as, 'Actually I

never spread out my hands at all to those rebels, but that's a secret.'

God calls to dialogue:

“'Come now, and let us reason together,'

says the Lord, “Though your sins are like scarlet, they shall be as white as snow;

though they are red like crimson, they shall be as wool.

If you are willing and obedient, you shall eat the good of the land;

but if you refuse and rebel, you shall be devoured by the sword;'

for the mouth of the Lord has spoken.”

(Isaiah 1:18-20).

Is it a dialogue or a monologue? Who, if anyone, is reasoning

together?: