|

Nations have, at times, gone through all the turmoil and drama of a revolution

only to conclude, in the end, that far from entering into a new birth of

liberty, they have exchanged one set of masters for another. The Russian

people, disgusted with their long servitude to a worthless

aristocracy, threw off that yoke. What filled the vacuum thence

resulting were the 'Nomenklatura,' the new class of communist

bureaucrats, who were not one whit less greedy and self-interested than

their predecessors, but differed from them only in being less competent,

less sympathetic and less interesting. And so they jettisoned, in their

turn, the 'Nomenklatura,' the privileged communist elite. Modern readers

cannot help but feel nostalgia for the deceased, departed 'author;'

though a pompous, egotistical, self-inflated wind-bag to be sure, at

least he sometimes made sense, which these newly ascendant literary

critics, who have not only declared but achieved their independence,

seldom do.

The story is told of a lady who attended a lecture by

American pragmatist William James. She approached him afterwards to

share her theory that the world rested upon the back of a giant

turtle. 'And upon what does that turtle rest, Madam?' asked he.

'Upon another turtle,' she replied. 'And upon what does this next

one rest, Madam?' the patient savant continued. A turtle, of course. The pragmatist

continued plodding on in this manner until the victorious lady

announced, 'It's no use, Mr. James. It's turtles all the way down!'

As Roland Barthes explains in the text cited above, "the structure

can be followed, 'run' (like the thread of a stocking) at every

point and at every level, but there is nothing beneath. . ." The

narrative rests, not upon the bed-rock of 'what actually happened,'

but upon another narrative, which in its turn rests upon yet a third

narrative. . .

Historical author David Barton is much exercised against the

post-modernists. But he is caught in their web. Every American

school-child has learned that the American revolution was made by a

handful of Virginia squires gathered together in a back room.

Because these men were slave-holders, we have grown disenchanted

with our founding fathers. Instead of sharpening his tools to drill down

through the inherited narrative to the bed-rock of actual reality which either

underlies, or shifts and fails to support it,

the post-modernist posits nothing but narrative, all the way down.

Like the lady's turtles, one narrative rests upon another; there is

no 'reality' down there at all. Although the jury may be forbidden

by the judge's instructions from disallowing testimony against which

no rebuttal has been brought, the post-modernist may believe

whichever narrative he likes best. . .even the school-child's

narrative, that a handful of Virginia squires made the American

revolution. Two faces carved on Mount Rushmore, Thomas Jefferson and

George Washington, are the revolution. Now this narrative has begun

to pall; modern readers dislike reviewing Jefferson's patronizing racist

drivel, and it's painful to be reminded that American slave-owners got a

harem in the bargain, along with a work force (even if the DNA

evidence leaves open the possibility it could have been Randolph,

his brother).

Manifestly we need a new narrative. Is it really so apparent that

this once popular narrative, that the revolution was made by a

handful of Virginia squires, has successfully drilled down to the

bedrock of very reality? Or is it not manifestly absurd to suppose

any revolution ever so made? Thomas Jefferson penned the Declaration

of Independence, a wonderful achievement to be sure; as Diana

Trilling said of Jean Harris, you either have this prose or you

don't. But no history of the twentieth century will single out Peggy Noonan

as the decisive figure, unless perhaps she goes on to be elected

President in her own right. The Declaration was a clarion call to war; but its author was

personally deaf to the bang of his own war-drums. Though not a

pacifist like his Quaker friends, Thomas Jefferson never fired a

shot in anger. . .at anybody. Molly Pitcher risked more of her own skin

in defense of the revolution than did this man. Please note, I'm not

finding fault: there was no military draft in that day, even the

European despotisms were defended by professional/volunteer forces.

Jefferson violated no law in failing to enlist; he evidently felt

military matters were best left to specialists in the

field. But is a man whose battle cry was 'See you later' the obvious

choice for Mr. Revolution?

Benjamin Franklin expressed the mindset in his ditty, "The King's

Own Regulars; and Their Triumphs over the Irregulars,"

"As they could not get before us, how could they look us

in the face?

We took care they should not, by scampering away apace;

That they had not much to brag of, is a very plain case.

For if they beat us in the fight, we beat them in the race."

(Angelic Music, by Corey Mead,

p. 45).

Thomas Jefferson was a revolutionary fighter after the style of

Franklin's hero; the enemy never had the opportunity of looking him in

the face, because he was long gone.

If you plan to spend your vacation visiting the great

revolutionary battle-fields of Virginia, please do not trouble to

stuff your satchel with very much clothing and supplies. When

General Cornwallis' troops advanced toward Charlottesville, the

latest temporary capital not yet abandoned, did they find their path

blocked by an embattled farmer, Thomas Jefferson, musket in hand?

No, nothing hindered their progress, nor had for some time. Thomas Jefferson, at

that time governor of the state, had skedaddled. Oddly for the

Parent of our Liberties, he spent the ensuing months in private

retirement at a farm (not Monticello, left abandoned). The Virginia

legislature subsequently convened an inquiry, wondering at the

swiftness with which Mr. Revolution had abandoned his duties. Nor

had he reached out thereafter to restore any functional membrane of

an underground state government network. Virginia

was not the Kandahar province of the Americas. The angry mobs which

blocked the path of the red-coats in Massachusetts were not much in evidence there.

The fact that substantial portions of Massachusetts' populace opposed

monarchy in principle on religious grounds probably played some role in

this noticeable regional disparity. So what ever started the myth that Thomas Jefferson was a one-man

revolution? From such intractable clay, how was a patriot hero

forged? We were already practicing post-modernism the first time the story

was told, much less the last; this is not a story that rests upon the

bedrock of observed fact, it was willed into existence; people told the

story because they liked it, not because it happened that way.

Why was it necessary for the Virginians to be front and center in

the campaign for independence? John Adams wanted them to be. Not

only did he realize Thomas Jefferson wrote better than he did, he

did not want it to appear that a rebellious New England was dragging

the other colonies into revolution, even if that was in fact the case. If

you go looking for other heroes, applying a slightly different

filter, you may find them. Here are, according to PolitiFact, the

signatories of the Declaration of Independence who did not own

slaves. There are promising candidates for

review:

"John Adams, Samuel Adams, George Clymer, William Ellery, Elbridge Gerry, Samuel Huntington, Thomas McKean, Robert Treat Paine, Roger Sherman, Charles Thomson, George Walton, William Williams and James Willson." (PolitiFact Fact Check, politifact.com)..

But after all, when we finish drilling down through successive turtles

and narratives, what is left beneath all the myth-making is a kernel of real achievement. No doubt his authorship of

the beautifully written Declaration along with his life-long advocacy for individual rights

left the nation with a debt of gratitude to this man, Thomas Jefferson, and his

subsequent election to the presidency cast a long backward shadow

covering his rather thin and watery revolutionary resume.

Why was he made into 'the' hero of the revolution? Some people elevated

this man, no doubt, simply because they liked him. People do that.

Modern-day atheists call themselves the 'brights,' implying that

others are rather dim. Their predecessors called themselves the

'Enlightenment.' Their fingerprints are all over the French

Revolution, with predictably horrific results. Despising Christianity, once

they started killing, they could not stop; turning the other cheek was

"sinking man into a spaniel," as Tom Paine famously said, so violence

once unleashed becomes an avalanche. They would like to

claim credit for the more successful American Revolution as well,

but the causal nexus is difficult to trace. There were, patently, currents

of thought stirring the land altogether outside their orbit. But they were a

legitimate thread in the fabric: the pamphleteer

Tom Paine was one of their guys, and Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin

Franklin were somewhat under their influence; Jefferson had even

read the skeptic David Hume. Ergo, Jefferson was the Revolution.

Even if all the red-coats ever saw of him was the back fasteners of

his suspenders.

The first draft of history involves identifying who the players

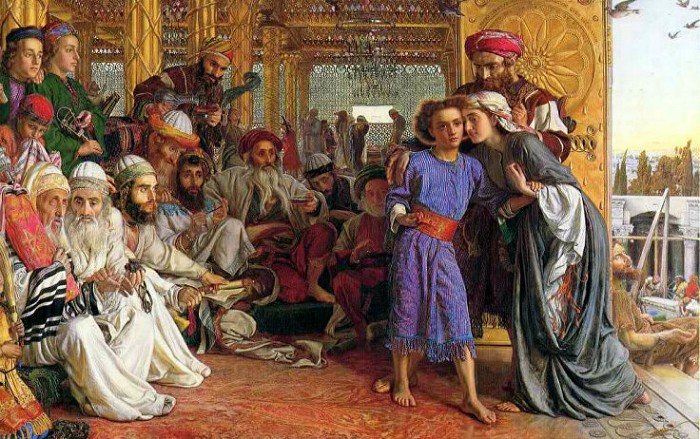

are. Viewing an oil painting of the signers of the Declaration of

Independence, who are the movers and shakers, versus the

guys who are just standing around? All these men, in truth, took great

risks in affixing their name to a document which would be perceived

as treasonous if they failed; “Only they would ever know what Rush

described as 'the solicitude and labors and fears and sorrows and

sleepless nights of the men who projected, proposed, defended and

subscribed the declaration of independence.'”

(Fried, Stephen. Rush: Revolution, Madness, and Benjamin Rush, the

Visionary Doctor Who Became a Founding Father (p. 162).)

Credit they all deserve, and a nation's gratitude.

Christian historians like David

Barton, if they want to be helpful, should not just borrow this

first draft from the secularists, unexamined and uncorrected. Is

Thomas Jefferson really the guy? Or was that elevation decided by people

overly sympathetic to his heterodox religious viewpoint? Or by Confederate

propagandists who wanted it understood that Virginia was the cradle

of liberty? There is no doubt that Deist authors like Thomas Paine

and Ethan Allen contributed to the Revolution; no one could deny

this, and in fact I have included Ethan's Allen's manifesto in the Thriceholy

library.

|