|

The reader will notice a certain asymmetry in the argument. We are

weighing two things in the balance; the same term occurs on both sides

of the equation, 'other people's testimony:'

The reader will notice a certain asymmetry in the argument. We are

weighing two things in the balance; the same term occurs on both sides

of the equation, 'other people's testimony:'

"The maxim, by which we commonly conduct ourselves in

our reasonings, is, that the objects, of which we have no

experience, resemble those, of which we have; that what we have

found to be most usual is always most probable; and that where there

is an opposition of argument, we ought to give the preference to

such as are founded on the greatest number of past observations."

(David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Section X Of

Miracles, Chapter 93.)

"[P]ast observations" conducted by whom; by ourselves? No, by

Other People. Worse, we have not ourselves gone and conducted a poll

of all these people, past and present; rather, we have been told

that other people say that. Legal thinking has traditionally sorted

testimony into several different bins, depending on whether it is

first-hand, eye-witness testimony, or whether it is second-hard

hearsay. On the Hume Express, we are not yet consistently doing that, which raises a red

flag; rather we are tossing apples into the bin with oranges.

It seems at times that we are going to count heads:

"It is experience only, which gives authority to human

testimony; and it is the same experience, which assures us of the

laws of nature. When, therefore, these two kinds of experience are

contrary, we have nothing to but subtract the one from the other,

and embrace an opinion, either on one side or the other, with the

assurance which arises from the remainder." (David Hume, An Enquiry

Concerning Human Understanding, Section X Of Miracles, Chapter 98).

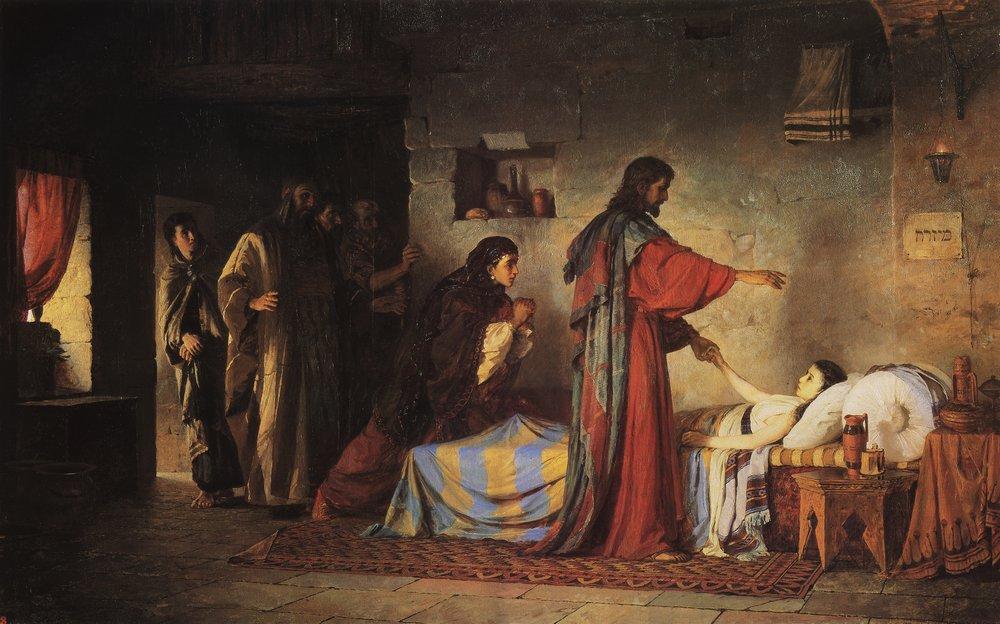

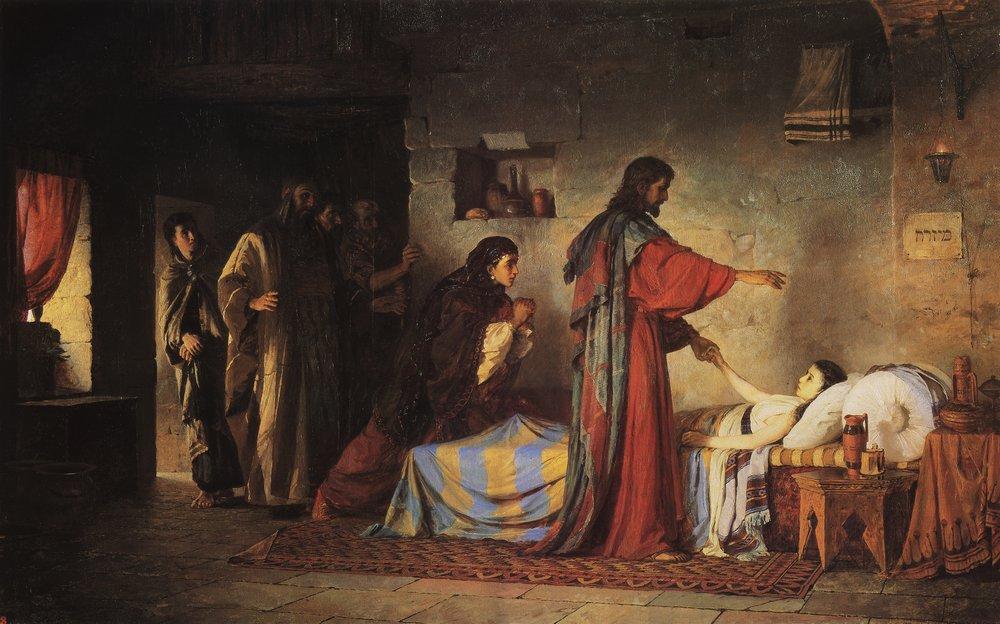

Simply counting heads, I reflect that I have heard more people

say, 'He is risen indeed,' then I have ever attended funerals and

noted that the deceased did not climb up out of the coffin. While

this great cloud of witnesses may testify, 'He lives within my

heart,' they do not count as eye-witnesses in the same sense as were the

"above five hundred brethren" of 1 Corinthians 15:6.

However, if we demand the same restriction to the other side of the

equation, my personal experience of dead men failing to rise from

the grave is based on an extremely small sample. So we augment it:

with what?— hearsay, what other people say. Not 'He is risen

indeed,' but 'No one has ever seen a dead man rise,' a fact not in

the speaker's experience, unless we are hearing the massed voice of

every man, woman and child who has ever lived, a voice as of many

waters.

Other people's testimony, on one side of the equation, is counted

ultimately for nothing; yet other people's testimony, on the other

side of the equation, provides us with a magic window into the

world; it is simply the way the world is. How, after all, do we know

it never happens that a man rises from the dead? Did we learn this

from observations conducted at the handful of funerals we ourselves

have attended, or are we juicing the results with hearsay, what

other people have told us? A row of zeroes adds up to zero, after

all. And how, after all, do we arrive at our skepticism of other

people's testimony? Because other people have told us to be

skeptical of other people's testimony. Realizing this becomes a hall

of mirrors, Hume wants to toss us back upon our own experience of

the reliability of other people's testimony, which assumes we

possess means to check their testimony by our own personal

inspection, which we generally do not. Perhaps some people's

testimony has conflicted with other people's testimony.

Shall we stroll into the hall of mirrors, doesn't it look

inviting? Hume does make an effort to separate the sheep from the

goats, the Other People whose testimony we choose to discount from

the Other People whose testimony seals the deal that a man cannot rise from

the dead. It is however simply intolerable. Guess what: it's based on social

status. Can anyone seriously claim the apostles' eye-witness testimony should

be discounted because they were not socially prominent? Justice is no respecter

of persons, as we learn in the Bible; the poor man's testimony cannot

be discarded simply because he is poor. Often in front of Western

court-houses a sculptured lady is placed, wearing a blind-fold over

her eyes. She is supposed not to notice Hume's criteria, as to the

"credit and reputation in the eyes of mankind" of our witnesses, or

whether they live in a "so celebrated a part of the world." She is

not supposed to let the blind-fold slip and notice that stuff, which are markers for social status, so

why should we? The lack of any pertinent first century evidence against the

resurrection, like a body, is simply because the right sort of folks,

persons of quality, had not yet deigned to notice this new sect:

"In the infancy of new religions, the wise and learned

commonly esteem the matter too inconsiderable to deserve their

attention or regard. And when afterwards they would willingly detect

the cheat, in order to undeceive the deluded multitude, the season

is now past, and the records and witnesses, which might clear up the

matter, have perished beyond recovery." (David Hume, An Enquiry

Concerning Human Understanding, Section X Of Miracles, Chapter 97).

"[P]erished beyond recovery"; well, isn't that a shame. This argument: that the wrong kind of people witness

miracles, whereas the right kind despise them, is not worthy of serious

consideration.

Notice further that Hume's argument against miracles would destroy, not only the church's

miracles, but much of modern 'science' as it is practiced today. Quite

frankly, Hume's broom would sweep out a good bit of rubbish,

unfortunately alongside of good things like the Big Bang. Modern

evolutionary biology purports to tell the story, based on various lines

of evidence, of one-time, non-repeatable events. These events are

conceded to be inherently unlikely; we have not ourselves seen them, nor

could produce them at all. In David Hume's terms, we have no warrant for

believing in these events; we judge what happened in the past only by

what commonly happens today.

|