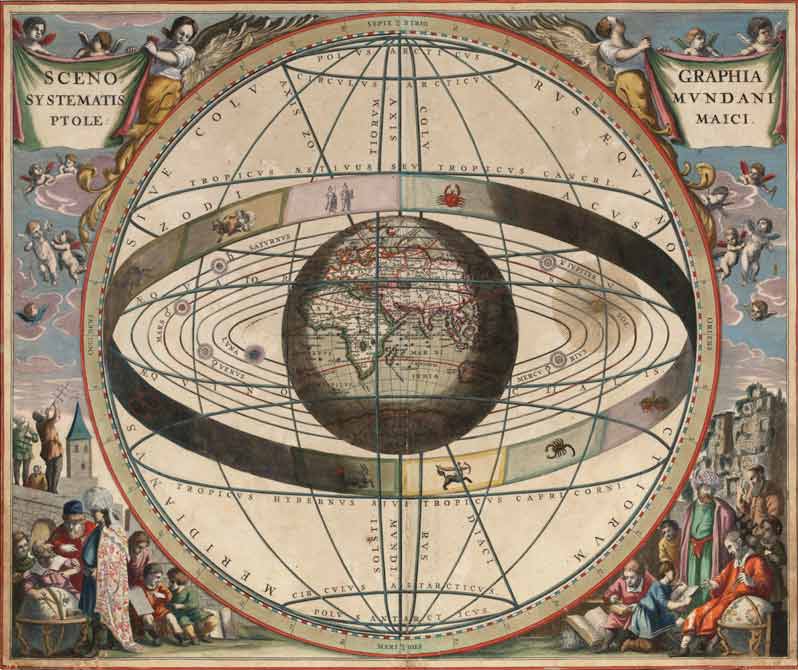

Equant

Above it was mentioned that Ptolemy's system is geocentric. That's true. . .approximately. Ptolemy used

several different constructions to model the orbits, including eccentric circles and the equant. The heavenly bodies are not necessarily orbiting around the center of the earth, but around a (moving) point somewhere in

the vicinity. Moreover these big circles are carrying epicycles,

smaller circles along for the ride, stubbornly pursuing their own

motion even as they are carried along the larger orbit. The system

is dauntingly complex. Copernicus, though retaining epicycles, was

able to simplify the system by running the planets around the sun.

Proponents of the Ptolemaic system understood that the system had

departed from perfect geocentricity: "...for according to Ptolemy,

the motion of the planets is in eccentrics and epicycles, which are

motions, not around the middle of the world, which is the earth's

center, but around certain other centers." (Thomas Aquinas, 'On the

Heavens,' Book I, Lecture 3, 28). The system ultimately departs from its

starting premises of geocentricity and uniform circular motion, and

ends up vibrating and shimmying like a washing machine with an

unbalanced load.

Terrestrial Ball

Ptolemy's system was in its main features originated not by himself but by earlier astronomers.

His degree of originality is difficult to estimate: was he a mere

textbook compiler, or did he make significant improvements to the

system he inherited? The Renaissance would raise the cry, 'ad fontes,'

to the sources, but the medievals actually preferred derivative

commentaries and textbooks, if they were up-to-date. It is not even

necessary to call it the 'Ptolemaic' system, if in so doing you will

spray your interlocutor with saliva.

Ptolemy's contemporary acceptance was not universal, but the widespread belief

that has established itself amongst atheists that everyone prior to Christopher

Columbus thought the earth was flat is baseless. When the hymn-writer sings,

"Let every kindred, every tribe,

On this terrestrial ball,

To Him all majesty ascribe,

And crown Him Lord of all;

To Him all majesty ascribe,

And crown Him Lord of all!

(All

Hail the Power of Jesus' Name)

...it is foolish to insist the question of flat-earthism remains open.

And writers in antiquity also commonly called the earth a globe or an orb.

The 'world' can refer to just the earth, or to the entire

world-system, which in the Ptolemaic system is also a sphere:

"Our own nation, whose history Africanus traced from its

beginnings in yesterday's discourse, now holds sway over the whole

world [orbis terrae]." (Marcus Tullius Cicero, On the

Commonwealth, Book III, Chapter XV).

"For the human race was

born subject to the condition that they should guard the sphere

which you see in the center of the heavens and which is called

the earth [illum globum, quem in hoc templo medium vides, quae

terra dicitur]." (Marcus Tullius Cicero, On the Commonwealth,

Book VI, Chapter XV (Scipio's Dream).

"Do not attend, says he, to these idle and imaginary tales; nor to the operator and builder of the World, the God of Plato’s Timaeus; nor to the old prophetic dame, the 'Pronoia' of the Stoics, which the Latins call Providence; nor to that round, that burning, revolving deity, the World, endowed with sense and understanding; the prodigies and wonders, not of inquisitive philosophers, but of dreamers!"

(Marcus Tullius Cicero, On the Nature of the Gods, Book I,

Chapter VIII). . ."First, let us examine the earth, whose situation is in the middle of the universe, solid, round, and conglobular by its natural tendency; clothed with flowers, herbs, trees, and fruits; the whole in multitudes incredible, and with a variety suitable to every taste: let us consider the ever-cool and running springs, the clear waters of the rivers, the verdure of their banks, the hollow depths of caves, the cragginess of rocks, the heights of impending mountains, and the boundless extent of plains, the hidden veins of gold and silver, and the infinite quarries of marble."

(Marcus Tullius Cicero, On the Nature of the Gods, Book II,

Chapter XXXIX).

Some people say that Cicero does not really mean, or always mean, the

terrestrial globe when he talks about the globe of the earth. In the

classical languages, the word for 'earth' can mean either our home world as

a whole, or the dry land, or that stuff out in the garden you can sink your

hands into, where the earth-worms live. In some cases the reference is

to a 'circuit' of the earth, not the globe as a whole. Perhaps Cicero only means the

inhabited earth is a circle?: "When Cicero writes of the orbis

he sometimes means the habitable dry land, a disk rising above the waves,

and sometimes the whole globe of land and ocean." (The Invention of Science, David

Wootton, p. 150). The problem here is that the ancients did not, in

fact, think that Eurasia has the form of a circle, as indeed it does not. Other authors are down with the program

as well:

"Military discipline jealously conserved won the leadership of Italy for Roman empire, bestowed rule over many cities, great kings, mighty nations...made it from its origin in Romulus' little cottage into the summit of the entire globe [terrarum orbis]."

(Valerius Maximus, 'Memorable Doings and Sayings,' Book II.8).

"For he wisely realized that increase for Roman empire was to be asked for in the days when triumphs were sought on the near side of the seventh milestone, but for a people that possessed the greater part of the whole globe [terrarum orbis] it would be greedy to ask for more and abundantly fortunate if they lost nothing of what was already theirs."

(Valerius Maximus, 'Memorable Doings and Sayings,' Book IV.1).

"The magnanimous monarch, who had already embraced the entire globe [terrarum orbem] by his victories or expectations, in so few words shared himself with him companion." (Valerius Maximus, 'Memorable Doings and Sayings,' Book IV.7).

"The signal clemency of the divine leader kept this father safe, but

who would not think his daring more than human in that he did not yield

to one to whom the whole world [terrarum orbis] succumbed?"

(Valerius Maximus, 'Memorable Doings and Sayings,' Book V.7).

In his 'Phaedra,' Seneca warns that Hippolytus' chastity will be the end of mankind,

ruining the entire orb:

"The unwedded life let barren youth applaud; then will all that thou beholdest be the throng of one generation only and will

fall in ruins on itself. . .Come now, let love but be banished from

human life, love, which supplies and renews the impoverished

race: the whole globe [orbis iacebit squalido turpis situ]

will lie foul in vile neglect; the sea will stand empty of its fish; birds will be lacking to the heaven, wild beast to the woods,

and the paths of air will be traversed only by the winds."

(Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Phaedra, lines 466-480).

Incidentally, Seneca also mentions in passing the antipodes: "Fugitive,

traverse nations remote, unknown; though a land on the remotest

confines of the world hold thee separated by Ocean's tracts, though

thou take up thy dwelling in the world opposite our feet, though

thou escape to the shuddering realms of the high north and hide deep

in its farthest corner. . ." (Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Phaedra, lines

928-936). A sphere must of necessity have an opposite side, though whether

people inhabited these regions was necessarily controversial. It would

mean that the Romans, who thought they had conquered the inhabited

world, just about, really had never even laid eyes on much of it.

"For the earth is level in all directions; its sunken

and flat parts are only slightly lower than the elevated ones. It

approximates to the curved surface of a sphere [in rotundum orbis]. The seas also form

part of this, and they combine to create the regular shape of the

one globe." (Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Natural Questions, Book 3,

28.5).

"They [the mountains] are outdone by, or outdo, each other,

but none rises high enough for even the greatest of them to have

any significance in comparison to the whole universe. If this

were not so, we would not say that the whole earth is a ball.

The properties of a ball are roundness and a degree of evenness.

You must realize that this is the evenness you see in balls

used in games: the seams and the cracks do not really prevent

them from being described as equal in every direction. Just as

in this kind of ball those gaps are no obstacle to its appearing

round, in the same way lofty mountains are no obstacle in the

case of the whole earth either; their height is swallowed up in

a comparison with the whole world." (Lucius Annaeus Seneca,

Natural Questions, Book 4b, 11:2-3).

"Then he told how the god had

severed the expanse of sea and placed the round world [globum]

in the center of the system; how he appointed lofty Olympus to

be a habitation for the gods." (Silius Italicus, Punica, Book

XI, Kindle location 3280).

Cicero cavils against the antique poet Ennius for referring to

the 'arch' of heaven, even while holding a globe in his hand: "In

such metaphorical expressions, dissimilitude is principally to be

avoided; as, Caeli ingentes fornices, 'The arch immense of heaven;'

for though Ennius is said to have brought a globe upon the stage,

yet the semblance of an arch can never be inherent in the form of a

globe." (Cicero, On the Orator, Book III, Chapter XL, 162).

Given the ubiquity of referring to the world as a 'globe,' it is

hardly surprising to find a Christian author like Tertullian

following suit: "I suppose they did not think that, having been

published before the deluge, it could have safely survived that

world-wide [ante cataclysmum editam post eum casum orbis omnium rerum abolitorein salvam esse potuisse] calamity, the abolisher of all things."

(Tertullian, On the Apparel of Women, Book 1, Chapter 3).

Did the Christians erase the then-common cultural understanding that

the world is round? They did not, though nay-sayers like Lactantius

did exist. We can scarcely point fingers, when we have Kyrie Irving.

Were they simply unaware that the world was understood to be

round, this knowledge confined to a small elite? No; Hippolytus of Rome,

after a whirlwind historical tour of philosophy, similar to the one

Plutarch affords his readers, offers the reader numbers for the

circumference of the earth: "But the diameter of Earth is 80,108

stadii; and the perimeter of Earth, 250,543 stadii. . ."

(Hippolytus, The Refutation of All Heresies, Book

IV, Chapter 8, p. 55). Eratosthenes' number for the

circumference was slightly larger than this, 252,000 stadii. They

were not unaware. Hippolytus offers an endorsement of Ptolemy the

astronomer: "This Ptolemy, however — a careful investigator of

these matters — does not seem to me to be useless. . ." (Hippolytus,

The Refutation of All Heresies, Book IV, Chapter 12, p. 58). What

this endorsement lacks in enthusiasm it makes up in rotundity,

because Ptolemy was a round-earther.

Since the 'ball' and 'globe' language is boiler-plate, it comes as no surprise when Eusebius

puts the phrase in the mouth of the Emperor Constantine:

"The stars move in no uncertain orbits round this terrestrial globe."

(Eusebius, The Life of Constantine, Book 2, Chapter 58).

This language did not thereafter pass out of fashion:

"For all those things, which at present you witness in the Church of God, and which you see to be taking place under the name

of Christ throughout the whole world [totum orbem terrarum], were predicted long ages ago.

. .It was foretold not only by the prophets, but also by the

Lord Jesus Christ Himself, that His Church would exist

throughout the whole world [universum orbem terrarum], extended

by the martyrdoms and sufferings of the saints. . ."

(Augustine, On Catechizing the Uninstructed, Chapter XXVII,

Section 53.)

Readers of the Latin Vulgate have encountered this "orb," translating

Greek words which have no particular spatial implications: "And it came

to pass in those days, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus,

that all the world should be taxed. [factum est

autem in diebus illis exiit edictum a Caesare augusto ut describeretur

universus orbis]" (Luke 2:1). It is eccentric to say the very least for speakers who believe the earth is flat to call it an 'orb' or 'globe.'

The pagan Ptolemy thought it was round, the early Christians thought it was

round, taking this view uncritically from their culture. But some people

dissented; the great natural poet Lucretius was not a round-earther, nor

were two named Christians of the early period, Lactantius and Cosmas

Indicopleustes. Does the dissent of two individuals legitimize the claim

that the early church believed in a flat earth?:

|