|

The more gifted among human authors, such as Herman Melville, are capable of

writing at multiple levels and imbuing their works with esoteric, as

well as an obvious, meaning. God is similarly gifted. At its most

basic, literal level, it is a mistake to assume that all references

to the 'earth' are written from the standpoint of an observer

outside the system, whether he thinks the earth is a globe,

dish-shaped or whatever. This is simply not an available viewpoint

at that level. It is interesting to see how much meaning

sophisticated readers like Hugh Ross can find in the Genesis text;

these readers are not necessarily reading into the text or importing

foreign material, even though considerable time would inevitably

elapse until readers could catch up to the Author's level of

insight. However reading into the text an imaginary construct, the

'sky-dome,' believed in by none, shines no light and uncovers no

meaning.

Language as She is Spoke

The Bible nowhere teaches that the earth is flat nor that it is covered by an inverted Revere-ware bowl, painted blue. Atheists will sometimes concede that it doesn't teach this: there is no deliberate presentation of any such doctrine. This in

itself is odd given that atheists imagine such structures as the 'sky-dome'

to be at the heart of the religious enterprise. But they go on to accuse,

not any Bible author, but the Hebrew language of flat-earthism.

At this the reader must cry 'foul.' Though it is reasonable to expect a

thoughtful writer to choose words carefully, which includes being mindful

of their etymologies, it is not reasonable to expect any author, human

or divine, to offer a warranty behind the origin each and every word of

a language he or she consents to speak. No one ever makes this extravagant

demand in any other context, so why is it justified here? Etymologies are

always speculative; do you know the history of the English words you use,

and will you stand behind them? Adam gave names to the animals, he did

not learn their names from God. Gagging God in this way requires Him to

introduce a divine Esperanto to His prophets before He can communicate

with them, filled with newly coined words of immaculate descent. But how

will He teach this new language to His prophets, without using words from

the old? So He must use existing languages, all of whose words have a past,

perhaps even a sordid past. But all current words have outlived their past,

they have faced it down and gone onward; it is not entirely relevant, because words mean what they are used to mean; etymology belongs to history.

Most speakers are not even aware of etymology: "We must accept the

obvious fact that the speakers of a language simply know next to

nothing about its development; and this certainly was the case with

the writers and immediate readers of Scripture two millennia ago."

(Moises Silva, Biblical Words and Their Meaning, Kindle location 487).

Certainly the omniscient God knows what the immediate speakers may

or may not know; but why God would be presumed to 'mean' the

etymologies when no one else does is unclear.

The word 'firmament' is 'raqiya'. Atheists, going behind God's revelation to the vocabulary of the already

existing human language He employed, claim that on its face this word propounds

the 'sky-dome' theory. It means something beaten out, as gold into fine gold

leaf. This is why the word is often translated 'expanse': "Then God

said, 'Let there be an expanse in the midst of the waters, and let it separate

the waters from the waters." (Genesis 1:6 NASB). In Biblical meteorology,

there is a lower ocean, the surface waters...and an upper ocean, the clouds:

"Or who shut up the sea with doors, when it brake forth, as if it

had issued out of the womb? When I made the cloud the garment thereof,

and thick darkness a swaddling-band for it. . ." (Job 38:8-9). God used

this already existing word with clear meaning. If anyone asked, 'What is it?,' the speaker could point.

The atheists say, language speakers must at some point have believed

in a metal sky dome, or otherwise why use such a word? Perhaps to

point to the lack of granularity? Who knows?

Nor is it reasonable arbitrarily to rule out otherwise available uses of

language. Who propounded the rule that we can use simile and metaphor,

but God cannot? One paramount 'dome' proof-text is Job 37:18: "Hast

thou with him spread out the sky, which is strong, and as a molten looking

glass?". But we find similar imagery in modern poets. Was Coleridge

a flat-earther?: "All in a hot and copper

sky, The bloody Sun, at noon, Right up above the mast did stand, No bigger than the Moon."

(Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Rime

of the Ancient Mariner). What I think Coleridge meant by his "copper sky" is the shimmery, scintillating appearance of

a blindingly hot day when it is almost hurtful to look at the bright, searing sky, even away from the sun itself. Poets

signify this by visualizing the sky itself as a burnished reflector of highly polished metal: a "molten looking glass".

The Bible uses a range of descriptive imagery of the sky, including tents, curtains, fabric scrims, and garments:

"And all the host of heaven shall be dissolved, and the heavens shall be rolled

together as a scroll: and all their host shall fall down, as the leaf falleth off from the vine, and as a falling fig from

the fig tree." (Isaiah 34:4);

"Who coverest thyself with light as with a garment: who stretchest out the heavens

like a curtain:..." (Psalms 104:2);

"And, Thou, Lord, in the beginning hast laid the foundation of the

earth; and the heavens are the works of thine hands: they shall perish; but

thou remainest; and they all shall wax old as doth a garment; and as a

vesture shalt thou fold them up, and they shall be changed: but thou art

the same, and thy years shall not fail." (Hebrews 1:10-12).

So are these 'competing theories': the 'scroll' theory, the 'curtain' theory, and the 'garment' theory? Or just

mixed metaphors? None of the apocalyptic authors describe the banging and denting required to trash a metallic dome; had they

imagined there to be any such structure, they would have been obliged to bring suitable means to bear to demolish it. Yet

there's no mention of taking a wrecking ball to any solid 'sky dome'. Which is hardly surprising; probably they didn't even know

it was there...which it isn't.

Flat Earth and the Ptolemaic System

Atheists allege that the early church writers believed in a flat earth.

They will even tell you that everyone prior to the voyages of

discovery of Christopher Columbus and Ferdinand Magellan

believed the earth was flat. The ancients, all of 'em, were

flat-earthers. The modern academy is heavily invested in

promoting this Ripley's 'Believe it or Not' conception: "Of course,

Herodotus's world is still flat — that notion

would stand for another thousand years."

(Nell Irvin Painter, The History of White People, p. 222).

So they say. But is it so? Did the early church writers believe in a flat earth? Why, then,

do some early church authors, like Clement of Alexandria and Origen,

employ technical terminology of Ptolemaic astronomy? Believe it or not, the Ptolemaic

system features a round earth.

Not only did Claudius Ptolemy, who wrote in second century

Alexandria, think the earth was round, he had arguments for a round earth which are downright compelling:

"Now, that also the earth taken as a whole is sensibly spherical,

we could most likely think out in this way. For again it is possible

to see that the sun and moon and the other stars do not rise and set at

the same time for every observer on the earth, but always earlier for those

living towards the orient and later for those living towards the occident...And

since the differences in the hours is found to be proportional to the distances

between the places, one would reasonably suppose the surface of the earth

spherical...Again, whenever we sail towards mountains or any high places

from whatever angle and in whatever direction, we see their bulk little

by little increasing as if they were arising from the sea, whereas before

they seemed submerged because of the curvature of the water's surface."

(Ptolemy, Almagest, I.4).

Ptolemy's astronomy was not pre-scientific; it had high predictive value.

Those church writers who accepted it were doing no more than believing

the best secular science of their day. There's certainly room for improvement,

as Ptolemy's system is geocentric. But the flat earth of the atheists can't

be found therein.

Ptolemy's originality is difficult to gauge, because works by his predecessors

have been lost. Aristotle, who does not provide a detailed astronomy, does

however describe the earth as spherical:

"Either then the earth is spherical or it is at least naturally spherical...The

evidence of the senses further corroborates this. How else would

eclipses of the moon show segments shaped as we see them? As it is,

the shapes which the moon itself each month shows are of every kind straight,

gibbous, and concave -- but in eclipses the outline is always curved: and,

since it is the interposition of the earth that makes the eclipse, the

form of this line will be caused by the form of the earth's surface, which

is therefore spherical. Again, our observations of the stars make

it evident, not only that the earth is circular, but also that it is a

circle of no great size. For quite a small change of position to

south or north causes a manifest alteration of the horizon. There

is much change, I mean, in the stars which are overhead, and the stars

seen are different, as one moves northward or southward. Indeed there

are some stars seen in Egypt and in the neighborhood of Cyprus which are

not seen in the northerly regions; and stars, which in the north are never

beyond the range of observation, in those regions rise and set."

(Aristotle, On the Heavens, Book II, Part 14).

I've provided a copy of Aristotle's On the Heavens in the

Thriceholy library, in hopes of combating the persistent misperception that, prior to Copernicus, astronomers believed the earth was flat.

The Ptolemaic system is geocentric -- it situates the earth at the center -- but the earth in that system

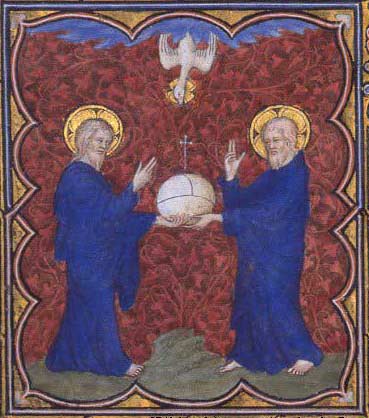

is as round as in any other. Plato also describes a spherical world system:

"...and if a person were to go round the world in a circle, he would often, when standing at the antipodes of his former

position, speak of the same point as above and below; for, as I was saying just now, to speak of the whole which is in the form of a globe

as having one part above and another below is not like a sensible man."

(Plato, Timaeus, 63)

Who started the trend? It is difficult to say, but Diogenes Laertius names Anaximander (611-546 B.C.) as a round-earther: "He held. . .that the earth, which is of spherical shape, lies in the midst, occupying the place of a centre; that the moon, shining with borrowed light, derives its illumination from the sun. . .He was the first to draw on a map the outline of land and sea, and he constructed a globe as well." (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, Volume I, Book II, p. 131, Loeb edition.) Who started the trend? It is difficult to say, but Diogenes Laertius names Anaximander (611-546 B.C.) as a round-earther: "He held. . .that the earth, which is of spherical shape, lies in the midst, occupying the place of a centre; that the moon, shining with borrowed light, derives its illumination from the sun. . .He was the first to draw on a map the outline of land and sea, and he constructed a globe as well." (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, Volume I, Book II, p. 131, Loeb edition.)

Not all the ancients were geocentrists. The

heliocentric hypothesis was formulated in antiquity by, among others, Aristarchus of Samos:

"His hypotheses are that the fixed stars and the sun remain unmoved, that the earth revolves about the sun in the circumference of a circle, the

sun lying in the middle of the orbit. . ." (Archimedes, The Sand-Reckoner, p. 420, The World of

Mathematics, Volume One, James R. Newman). The reasons why the early astronomers rejected the heliocentric hypothesis were not religious but physical. First, there was the lack of stellar

parallax: "The earth, then, also, whether it move about the center or as stationary at it, must necessarily move with two motions.

But if this were so, there would have to be passings and turnings of the fixed stars. Yet no such thing is observed. The same stars

always rise and set in the same parts of the earth. "

(Aristotle, On the Heavens, Book II, Part 14).

Passengers on a train watch telephone poles change their configurations

respective to one another as the train rolls through the countryside. If

the earth is moving through space, why is there no observable change in

the configuration of the stars? Ptolemy, too, notes the absence of

observable stellar parallax: "...in all parts of the earth the sizes

and angular distances of the stars at the same times appear everywhere

equal and alike...By the same arguments...it can be shown that the earth

can neither move in any one of the aforesaid oblique directions, nor ever

change at all from its place at the center." (Ptolemy, Almagest I.6-7).

Stellar parallax was not observed until the nineteenth century. This,

thought Ptolemy, was observational proof against the earth orbiting the

sun. To rebut this observational evidence, later astronomers hypothesized

immense distance: but is that parsimonious?

What about rotation? If the earth rotates, the ancients wondered,

why does a rock thrown upwards land directly beneath the point from which

it was thrown? "...for us to grant these things [earth's rotation],

they would have to admit that the earth's turning is the swiftest of absolutely

all the movements about it because of its making so great a revolution

in a short time, so that all those things that were not at rest on the

earth would seem to have a movement contrary to it, and never would a cloud

be seen to move toward the east nor anything else that flew or was thrown

into the air. For the earth would always outstrip them in its eastward

motion, so that all other bodies would seem to be left behind and to move

towards the west." (Ptolemy, Almagest I.7).

Copernicus bravely meets these objections head on: "Moreover, freely falling bodies would not arrive at the places appointed

them, and certainly not along the perpendicular line which they assume so quickly. And we would see clouds and other things floating

in the air always borne toward the west. For these and similar reasons they say that the Earth remains at rest at the middle of the world

and that there is no doubt about this." His answer: "And things are as when Aeneas said in Virgil: 'We sail out of the harbor,

and the land and the cities move away.' As a matter of fact, when a ship floats on over a tranquil sea, all the things outside seem to the

voyagers to be moving in a movement which is the image of their own, and they think on the contrary that they themselves and all the things

with them are at rest." (Copernicus, Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, I.7-8). It took Galileo's genius to work out this 'ship' analogy

in sufficient detail to quiet doubt. It was physics which lagged, not astronomy; no one in antiquity could explain how, on a moving earth,

a projectile thrown directly upwards would land at a spot directly beneath where it was thrown.

While various conformations of the earth had been suggested by the earliest

astronomers, Pliny reports no ongoing dispute:

"Of the Form of the Earth: Every one agrees that it has the most perfect

figure. We always speak of the ball of the earth, and we admit it to be

a globe bounded by the poles." (Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, 2.64).

Cicero too speaks of a globe: "Exile is terrible to

those who have, as it were, a circumscribed habitation; but

not to those who look upon the whole globe, but as one city [qui omnem orbem terrarum

unam urbem esse ducunt]." (Complete Works of Cicero,

Kindle location 47301, Paradoxes Addressed to Marcus Brutus, Paradox II). As Cicero describes it, the earth is "solid, round, and

conglobular: "First, let us examine the earth, whose situation

is in the middle of the universe, solid, round, and

conglobular by its natural tendency; clothed with flowers,

herbs, trees, and fruits; the whole in multitudes incredible,

and with a variety suitable to every taste: let us consider

the ever-cool and running springs, the clear waters of the

rivers, the verdure of their banks, the hollow depths of

caves, the cragginess of rocks, the heights of impending

mountains, and the boundless extent of plains, the hidden

veins of gold and silver, and the infinite quarries of

marble."

(Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Delphi Complete Works of

Cicero (Delphi Ancient Classics) (Kindle

Locations 57559-57563). On the Nature of the

God, Book II, Chapter XXXIX).

There were nay-sayers in the early church on the subject of Ptolemaic astronomy,

but the Ptolemaic system was generally popular, round earth and all. It

would later come to be much beloved by scholastics like Thomas Aquinas.

Reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin were also fond of it. Galileo's

conflict with Roman Catholic authorities over the moving earth of the Copernican

system has come, by some confused channel whereby atheist polemic bleeds

over into the 'history of science,' to be misunderstood as a dispute

over whether the earth is flat or round. There was no such dispute; the

scholastics describe a round earth.

The pagan philosopher Pythagoras was a 'round-earther:' ". .

.these elements interchange and turn into one another completely, and

combine to produce a universe animate, intelligent, spherical, with

the earth at its center, the earth itself too being spherical and

inhabited round about. There are also antipodes, and our 'down' is

their 'up.'" (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers,

Pythagoras, Chapter VIII, p. 343 Loeb).

Notice how Justin, and others amongst the earliest Christian apologists, quote with approval 'round earth' astronomy:

- “And Pythagoras agrees with him when he writes: — 'Should one in boldness say, Lo, I am God! Besides the One

— Eternal — Infinite, Then let him from the throne he has usurped put forth his

power and form another globe, such as we dwell in, saying, This is mine.'”

- (Justin on the Sole Government of God, quoting Pythagoras' testimony to

the one God, Chapter II).

- “Beautiful without doubt is the world, excelling, as well in its magnitude

as in the arrangement of its parts, both those in the oblique circle and

those about the north, and also in its spherical form.”

- (Athenagoras, A Plea for the Christians, Chapter 16).

- “Lord of the good, Father, of all the Maker, Who

heaven and heaven’s adornment, by Thy word

Divine fitly disposed, alone didst make; Who

broughtest forth the sunshine and the day; Who

didst appoint their courses to the stars, And

how the earth and sea their place should keep;

And when the seasons, in their circling course,

Winter and summer, spring and autumn, each

Should come, according to well-ordered plan; Out

of a confused heap who didst create This ordered

sphere, and from the shapeless mass Of matter

didst the universe adorn; — Grant to me life,

and be that life well spent, Thy grace enjoying;. . .”

- (Clement of Alexandria, Hymn to the Paedagogus, p.

584, ECF_0.02).

- “As, when the sun shines above the earth, the shadow

is spread over its lower part, because its spherical shape makes it impossible for it to be

clasped all round at one and the same time by the rays, and necessarily, on whatever side the sun’s

rays may fall on some particular point of the globe, if we follow a straight diameter, we shall

find shadow upon the opposite point, and so, continuously, at the opposite end of the direct

line of the rays shadow moves round that globe, keeping pace with the sun, so that equally in

their turn both the upper half and the under half of the earth are in light and darkness; so, by this

analogy, we have reason to be certain that, whatever in our hemisphere is observed to befall

the atoms, the same will befall them in that other.”

- (Gregory of Nyssa, On the Soul and the

Resurrection, p. 860, ECF_2.05).

- “For they say that the

circumference of the world is likened to the

turnings of a well-rounded globe, the earth

having a central point. For its outline being

spherical, it is necessary, they say, since there

are the same distances of the parts, that the

earth should be the center of the universe, around

which, as being older, the heaven is whirling.”

- (Methodius, Banquet of the Ten Virgins, Discourse

8, Chapter 14).

- “Thus we might, without self deception, define day as air

lighted by the sun, or as the space of time that

the sun passes in our hemisphere.”

-

(Basil, Hexaemeron, Homily 6, Section 8, p. 276, ECF_2.08).

- “For take, saith he, the comparison of ashes to a

house, of a house to a city, a city to a province,

a province to the Roman Empire, and the Roman

Empire to the whole earth and all its bounds,

and the whole earth to the heaven in which it is

embosomed; — the earth, which bears the same

proportion to the heaven as the center to the

whole circumference of a wheel, for the earth is no

more than this in comparison with the heaven:

consider then that this first heaven which is seen

is less than the second, and the second than the

third, for so far Scripture has named them, not

that they are only so many, but because it was

expedient for us to know so many only.”

- (Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures,

Lecture 6, Section 3).

- “. . .therefore I called Him

back as My true and beloved Son from the Egypt

whither He descended when He became man, meaning by

Egypt this earthly sphere, or possibly Egypt

itself.”

- (Eusebius of Caesarea,

Demonstratio Evangelica (The Proof of the Gospel),

Book IX, Chapter 4).

- “The sun and the moon have their

settled course. The stars move in no uncertain

orbits round this terrestrial globe.”

- (The Emperor Constantine, quoted in Eusebius, Life

of Constantine, Book Two, Chapter 58).

|

|

What you hear from the atheists is flat-out wrong: "All the early

Fathers naturally believed that the earth was flat." (H. L. Mencken, A

Treatise on the Gods, Kindle location 2922). The third-century Christian author Arnobius, debunking the pagan deities, one

of whom presided over the 'left hand,' explains why this deity is

somewhat beside the point in our spherical world,

"For in the first place, indeed, the world itself has in

itself neither right nor left neither upper nor under regions,

neither fore nor after parts. For whatever is round, and bounded on

every side by the circumference of a solid sphere, has no beginning,

no end; where there is no end and beginning, no part can have its

own name and form the beginning." (Arnobius, The Seven Books of

Arnobius, Book 4, Section 5, p. 891 ECF 0.06).

Later writers offer similar thoughts, taking for granted

the rotundity of the world:

“Ye have heard in the Psalm, 'I have seen the end of all perfection. He

hath said, I have seen the end of all perfection: what had he seen? Think

we, had he ascended to the peak of some very high and pointed mountain,

and looked out thence and seen the compass of the earth, and the circles of

the round world, and therefore said, 'I have seen the end of all

perfection'?” (Augustine, Homily on First John 5:1-3, Ten Homilies on

First John, Homily 10.5).

Though Augustine shares Lactantius' dislike for the antipodes, he concedes the rotundity of the earth:

“But they do not remark that, although it

be supposed or scientifically demonstrated that the world is of a

round and spherical form, yet it does not follow that the other side of the

earth is bare of water; nor even, though it be bare, does it

immediately follow that it is peopled.” (Augustine,

The City of God, Book 16, Chapter 9).

To close with Jerome, on the verge of the medieval period:

“Hardly had she escaped from the hands of the barbarians, hardly had she

ceased weeping for the virgins whom they had torn from her arms, when

she was overwhelmed by a sudden and unbearable bereavement, one too

which she had had no cause to fear, the death of her loving son. Yet as one

who was to be grandmother to a Christian virgin, she bore up against this

death-dealing stroke, strong in hope of the future and proving true of

herself the words of the lyric:

“Should the round world in fragments burst, its fall

May strike the just, may slay, but not appall.”

(Jerome, Letters, Letter CXXX, Chapter 7, p. 589, ECF_2_06).

“The whole world groaned, and was astonished to find itself Arian. [Ingemuit

totus orbis, et Arianum se esse miratus est.]” (Jerome,

Dialogue Against the Luciferians, Chapter 19).

It is a round world, after all, 'orbis' like the man says,

which when you stop to think about it is a peculiar word for flat-earthers

to be using for the world; our word 'orb' comes from the Latin orbis.

The atheists visualize a half-dome covering a flat surface and

try to find it where they may. The sky above us does seem to convey,

by its appearance, a spherical look and feel, though under the

Copernican system of astronomy, this can only be an optical

illusion. The popularity of domed structures, from the Pantheon

forward, is probably related to this conception: "Mankind has built

domed structures for over two thousand years and learned to

attribute to their geometry very particular psychological

properties. As a source of messages the architectural dome is

related to the celestial sphere, which can be interpreted as a dome

of infinite magnitude covering the whole of humanity. . .No other

surface can give the same feeling of protection because the sphere

is the only surface that comes down equally all around us. . .The

dome sends a complex and ambiguous message, composed of amazement,

awe and serenity." (Mario Salvadori, Why Buildings Stand Up, p.

278). Though a domed roof is, of necessity, never a complete sphere,

what the people who built these structures were actually thinking of

is a little different. The atheists seem strangely oblivious to the

persistence, for centuries, of a system of astronomy which featured

a whole-dome, or rather a series of nested concentric domes,

surrounding the earth. Unknown to them, what was matched with the

celestial sphere, fittingly enough, was a rotund, spherical earth.

This system is described, not only in technical literature

intended for astronomers, but in popular works addressed to the

public at large, both in antiquity and also during the Middle Ages;

think of Dante, with his layered (Ptolemaic) universe:

|