Proofs of God's existence

The Christian pursuit of natural theology goes back to Paul the apostle, who saw proof of God's reality in the

mute testimony of His creation: "For since the creation of the world His invisible attributes are clearly seen, being understood

by the things that are made, even His eternal power and Godhead, so that they are without excuse. . ."

(Romans 1:20). Natural

theology seeks to discover what may be known about God without recourse to His own revelation to mankind.

The common proofs of God's existence are wonderfully

non-sectarian; though often associated with Thomas Aquinas, who

inherited them from Muslim authors writing in Arabic, many go back

to the pagans. These proofs have, if nothing else, a didactic

function; atheists who first hear about 'God' often visualize a

cartoon figure, a comic-book character zooming about, whose real existence they find

as unlikely as anyone else would find it; encountering these proofs can be their first introduction

to the concept. Atheists point out that these proofs do not establish

the Christian gospel, and indeed they do not. Christian evangelists

point out that making an atheist into a deist leaves him hell-bound,

which is also true. But how can the gospel be preached, 'For God so

loved the world. . .' if your auditor can hear only, 'The tooth

fairy loved the world, the flying spaghetti monster loved the

world'? Once it is understood that the world was made by an

infinitely wise being, then it becomes meaningful to ask whether

that being has made any efforts to communicate with mankind, a part

of creation who are able to think His thoughts after Him, if only

haltingly.

With information derived from natural theology in hand, it becomes possible to validate God's

self-revelation in the Bible. The question, 'Who authored the Bible?', can be addressed

no differently from any other question of authorship or attribution: compare known works from the author's hand with the work whose

authorship is in dispute. Is this newly discovered sonata by Beethoven? Is that sonnet by Shakespeare? Absent documentary

or evidentiary authentification (to which the correlate in Bible study would be miracles), the investigator's strategy is

comparison with known works by that author's hand. There are competing

claimants, to be sure. But is the petty, score-settling god who took up space in the Koran to threaten

Mohammed's estranged uncle the same God who made the expansive Rocky Mountains? The only way to know is to find out first. . .just

who did make the Rocky Mountains, if anyone? Does God exist?:

A Posteriori Proofs

A posteriori proofs admit evidence derived from sensory experience of the world; a priori proofs do not. Here

are some common a posteriori proofs of God's existence:

Contingency

"For since something must needs have been from eternity,

as has been already proved, and is granted on all hands, either

there has always existed some one unchangeable and independent

being, from which all other beings that are or ever were in the

universe have received their original; or else there has been an

infinite succession of changeable and dependent beings, produced one

from another, in an endless progression, without any original cause

at all. Now this latter supposition is so very absurd, that though

all atheism must in its account of most things (as shall be shown

hereafter,) terminate in it, yet I think very few atheists ever were

so weak as openly and directly to defend it; for it is plainly

impossible, and contradictory to itself."

(Samuel Clarke. A

Discourse Concerning the Being and Attributes of God (Kindle

Locations 315-320).)

This proof does not ask much of the world; if there is only one thing which exists, which can be known to be contingent

through inventory of its concept, this proof is happy. After all, it's far from obvious that our sensory experiences give us

a peek into a 'real world' out there; though commonly assumed, the proof of this can be surprisingly elusive. Be that as

it may, from our own awareness, we can know 'there is something in the world which thinks'; this 'thinking thing' can serve as

our one contingent thing.

A 'contingent' thing is a thing which may be or not be; its existence is not necessary. To give a sufficient

reason for a contingent thing to exist, one must look outside it, beyond it either to another contingent or to a necessary being.

The world is filled with things whose existence depends upon other things; we realize this because they come and they

go, like smoke or vapor. If the cause for their existence lay within them, they would ever abide. We can recall times

when we were, but then we run into a brick wall; we are contingent beings. This is a matter of common observation: "Indeed,

You have made my days as handbreadths, and my age is as nothing before You; certainly every man at his best state is but vapor.

Selah." (Psalm 39:5).

If we admit the existence of even one contingent thing: a 'thinking thing' which was not always, say -- it follows

necessarily that there is also some necessary thing. Yet there is one contingent thing; therefore God also exists. The

hinge point is that everything cannot be contingent; if we set off down a daisy chain where one contingent thing derives its

existence from another, which in turns derives its existence from another contingent thing, we are in the state of an economy which

functions through everybody borrowing five dollars from one another: where did the five dollars come from to start the system?

Not everything can be contingent: "We find in nature things that are possible to be and not to be, since they are found

to be generated, and to be corrupted, and consequently they are possible to be and not to be. But it is impossible for these

always to exist, for that which is possible not to be at some time is not. Therefore, if everything is possible not to

be, then at one time there could have been nothing in existence. Now if this were true, even now there would be nothing in

existence, because that which does not exist only begins to exist by something already existing. Therefore, if at one time nothing

was in existence, it would have been impossible for anything to have begun to exist; and thus even now nothing would be in existence

-- which is clearly false. Therefore, not all beings are merely possible, but there must exist something the existence of which

is necessary...Therefore we must admit the existence of some being having of itself its own necessity, and not receiving it from

another, but rather causing in others their necessity. This all men speak of as God."

(Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, First

Part, Q. 2, Article 3).

Nothing that once did not exist can be the cause of its own existence. When it did not exist, how could it call

itself into being? Thus, all contingent things depend upon something outside themselves for their existence. If any contingent

thing exists in the world rather than nothing, then a necessary being must also exist.

"That there must have existed from eternity some one unchangeable and independent being, because, to suppose an eternal succession of merely dependent beings, proceeding one from another in an endless progression, without any original independent cause at all, is supposing things that have in their own nature no necessity of existing, to be from eternity caused or produced by nothing; which is the very same absurdity and express contradiction as to suppose them produced by nothing at any determinate time: That that unchangeable and independent being, which has existed from eternity, without any external cause of its existence, must be self-existent, that is, necessarily-existing:.

. ." (Samuel Clarke. A Discourse Concerning the Unchangeable

Obligations of Natural Religion, and the Truth and Certainty of

the Christian Revelation, in A Discourse Concerning the Being

and Attributes of God (Kindle Locations 2005-2009).)

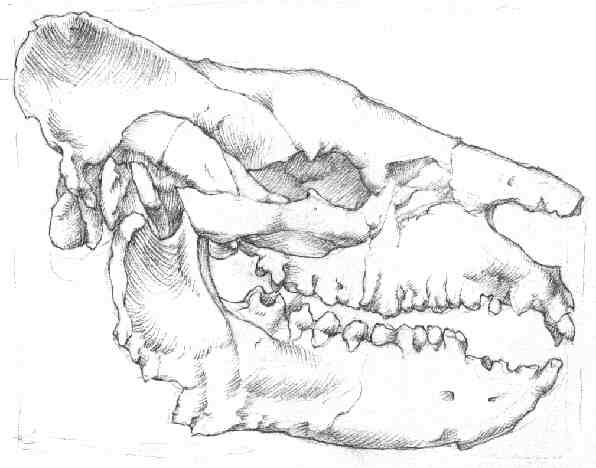

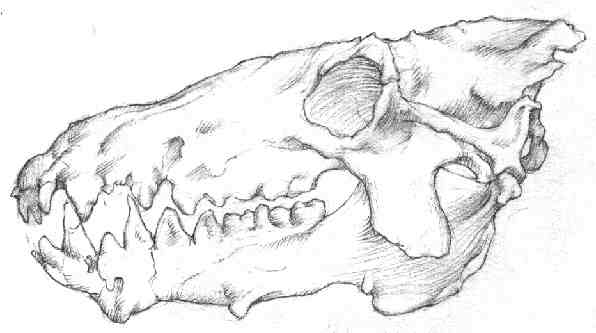

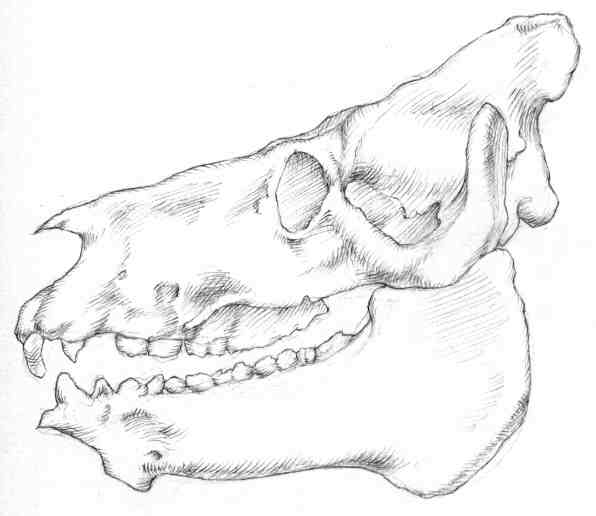

- "But ask now the beasts, and

they shall teach thee; and the fowls of the air, and they shall

tell thee: Or speak to the earth, and it shall teach thee: and the fishes

of the sea shall declare unto thee. Who knoweth not in all these that the

hand of the LORD hath wrought this?"

- (Job 12:7-9).

|

|

Order

As we cast our gaze about the world, we find the objects around us obeying natural law with wondrous docility.

Why is the world that way at all? Why do natural things conserve their own properties and behave in predictable fashion;

why doesn't water burn like gasoline on Monday, and quench fire on Tuesday? The very smallest things are not so accommodating,

so we know it need not be this way!

Why does the human day-dream of mathematics fit the world hand in glove -- just as if God were a mathematician?

Mathematics works, from from observation, but from the opposite direction, from deduction. Its objects are not even objects

in the world; no material thing is the triangle of the geometricians, only a feeble caricature thereof. Yet in the end mathematics

is found an apt model of the universe. How could that be, unless the mind that made the world thinks along the same lines?

Likewise, the world obeys law, just as if it trembled in fear of judgment. Law implies a law-giver.

When D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson set out, in his On Growth and Form, to detail the superfluity of order in the

world, sometimes called beauty, he found what he sought in gratuitous abundance. Intelligibility implies intelligence; the simplest

and most economical account for an intelligible world is an intelligent artificier.

|