|

One would like to think that the durable link between the old pagan

astronomy and astrology was nothing but a negative to be overlooked in

the scholastic evaluation of this science. One would like to think. That

is why it is disappointing to realize that Thomas specifically leaves in

his system a back door open to this pagan science:

"Now, the celestial bodies, alone among bodily

things, are inalterable; their condition shows this, for it is

always the same. So, the celestial body is the cause of all

alteration in things that are changed by alternation. . .Thus, it

is evident that lower bodies are ruled by God through the

celestial bodies." (Thomas Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles, Book

Three, Chapter 82, That Lower Bodies are Ruled by God through

Celestial Bodies, p. 277).

By the time of the Reformation, people were already sick of this

pagan/Christian hybrid, with good reason:

"What else are the universities, if their present

condition remains unchanged, than as the book of Maccabees says,

Gymnasia Epheborum et Graecae gloriae [2 Macc. 4:9, 12], in which loose

living prevails, the Holy Scriptures and the Christian faith are

little taught, and the blind, heathen master Aristotle rules

alone, even more than Christ. . .I venture to say that any

potter has more knowledge of nature than is written in these

books. It grieves me to the heart that this damned, conceited,

rascally heathen has with his false words deluded and made fools

of so many of the best Christians."

(Martin Luther, An Open Letter to the Christian Nobility of the

German Nation Concerning the Reform of the Christian Estate, Kindle

location 1723, Works of Martin Luther, Volume II, Part III,

Section 25).

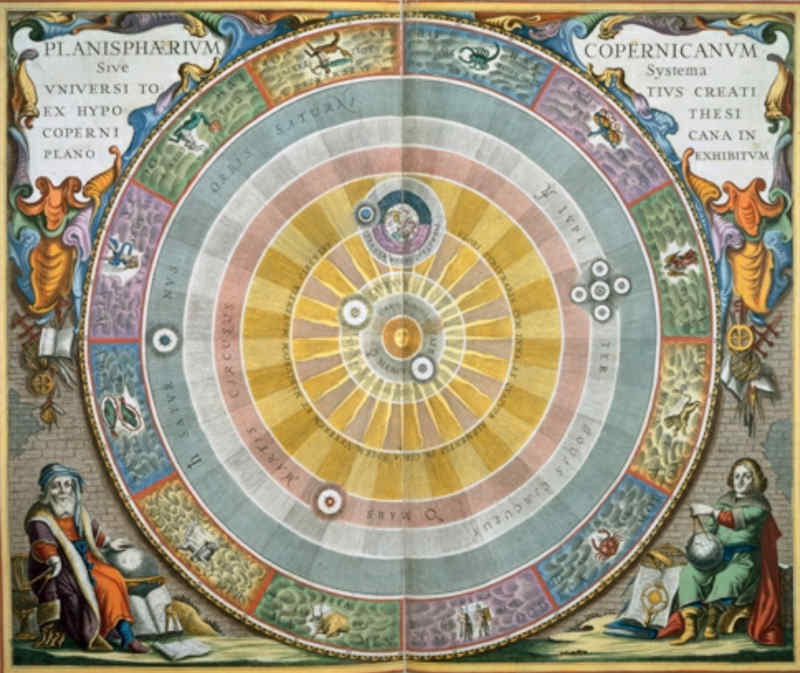

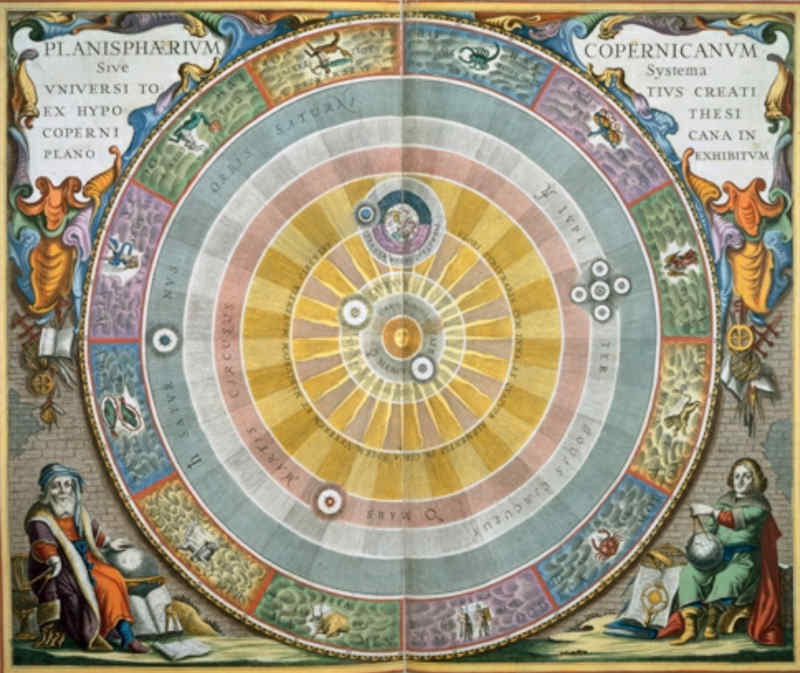

Which is not to suggest that Copernicus put the astrologers out of business; of course, he did not,

and they thrive to this day. Queen Elizabeth I's personal astrologer, John

Dee, may have been a Copernican heliocentrist. But it seems that he did open

a door toward demythologizing the heavens.

Galileo's Crime

Why did the Catholic Church feel obliged to protect Ptolemaic

astronomy against Galileo's attacks? And where is it taught in the

Bible? It is not found in the Bible, but in the works of Thomas Aquinas.

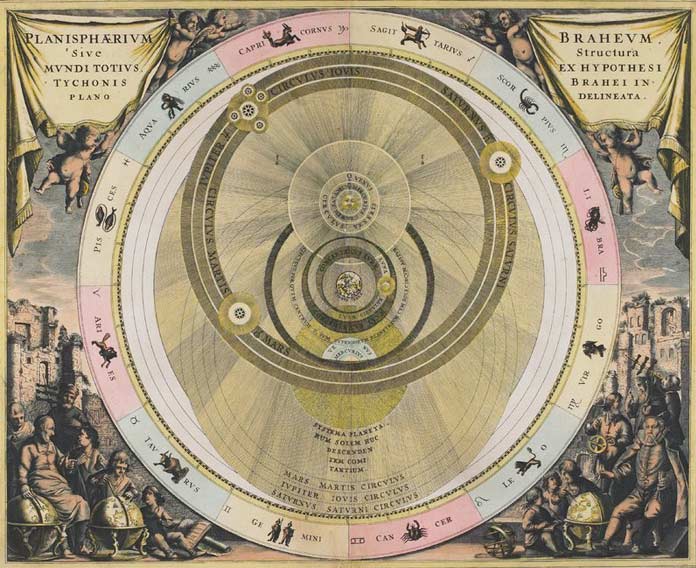

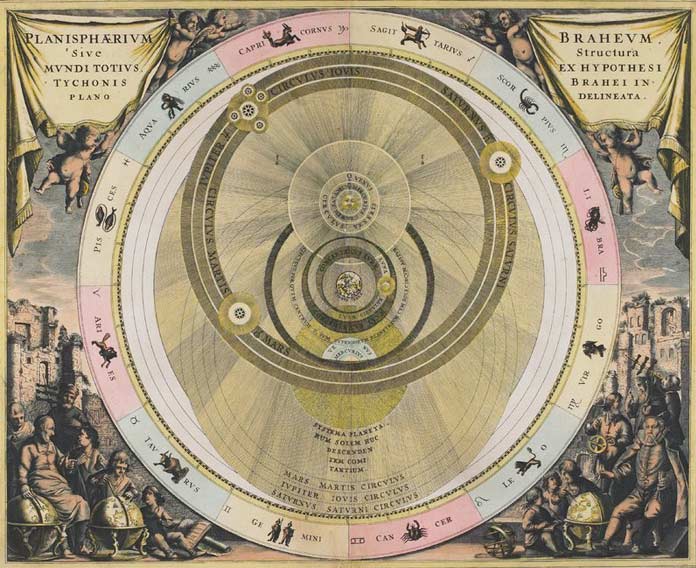

That's the long and the short of it. Thomas lived too early to have

encountered Tycho Brahe's innovative theory, so defense of that theory,

neither in the original nor in its Jesuitical refinement,

cannot vindicate Thomas. And it was Thomas they cared about. They

thought that medieval inquiries had nailed down a comprehensive

'theory-of-everything,' which might bear improvement in small details,

but could not be substantially wrong. Copernicus himself, no publicity

hog, had flown under the radar, but Galileo wanted the public to

understand that Ptolemaic astronomy had been decisively refuted. Venus

displays phases, just like the moon, and he had looked through his

telescope and seen them — seen them all, although the Ptolemaic orbits

do not allow Venus to stand opposed to the sun, thus appearing fully lit

from earth. If Venus is drawn below the sun, as commonly represented, it

could not appear as an illuminated circle; reversing the positions does

not fix the problem. But Galileo had seen it and wanted to shout it from the roof-tops.

Venus goes through all the phases, like the moon. Because the

sun never sees a shadow, the phases of Venus give us another viewpoint

besides our own. The licentious Renaissance popes lived under the banner, 'Do whatever

you like, dear, only don't do it in the street and frighten the

horses.' They had not cared about Copernicus, but could not avoid conflict

with Galileo.

Ptolemy and Copernicus did not in general make dramatically different

predictions about the appearance of the heavens. The Ptolemaic system

did not fail to save the appearances. However advocates for the

Copernican system ferreted out a few subtle clues. The

apparent size of Venus, even to the naked eye, is a stumbling block for

the Ptolemaic system, or so they felt. At its biggest and brightest,

Venus alarms people into calling 911 and reporting it as a UFO. But

sometimes it is inconspicuous. If the Ptolemaic system were correct and

Venus were orbiting in a circle about the earth (albeit an eccentric

circle, and albeit carried on an epicycle), its distance from earth and

consequently its apparent size might vary, but not to the extent

observed. Nor would it display the full menu of phases, as it does. To

the naked eye, the phases cannot be distinguished; a crescent Venus is a dim

Venus, but the introduction of the telescope pried apart the two questions. The heliocentric system explains this change in visible size handily,

because as the planets race around their nested race-tracks, the

distance between them can vary quite a lot, and Venus is also liberated

to display the lunar-like phases it shows to the telescopic observer.

Admittedly, this point remained open to dispute, with some hold-outs alleging

the observed variation in Venus' apparent size is not as great as it

should be under the Copernican system. But on this point the two systems

do make divergent predictions, opening up the debate to potential

empirical test. The phases of Venus are a problem for Ptolemy, not for

Tycho, in whose system Venus orbits the sun, just like it does in Copernicus. But Tycho lacks traditional advocates.

An additional observation difficult for geocentrism is that of a

swinging pendulum, suspended from a pivot made as frictionless as

possible; it will trace a circle, why? People who think Ptolemy can

be vindicated in the end should just give it up. And vindicating

someone other than Ptolemy serves no purpose. Two books were placed

on the altar at the counter-reformation Council of Trent: the Bible

and Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologica. The Catholic Church had placed

all its bets on this medieval author; when reformers like Martin

Luther mounted Biblical arguments against practices built on Thomas'

doctrinal innovations, such as indulgences, the battle lines were

drawn. They would not abandon this uninspired if brilliant author,

who then and thereafter became an idol to the Roman Catholic Church.

As late as the nineteenth century they were demanding fealty to his

teachings. That is why Galileo was indigestible to the Church. The

Catholic Church does, or did, have an astronomy, and that astronomy

is Ptolemaic. The Catholic Church does, or did, have a physics, and

that physics is Aristotelian. Neither Ptolemy nor Aristotle,

pagans both, knew or cared about the Bible. That, in a nutshell, is

why heliocentrism proved hard for the Catholics, but easy, in the

end, for the Protestants; who were not necessarily, however, early

adopters.

|