Pythagoras' Mother Pythagoras' Mother

Pythagoras, the first man to call himself a 'philosopher,' was

the founder of a religious sect who made extravagant claims for

himself. His awed followers called him, not Pythagoras, but 'that

man.' According to a skeptic, Pythagoras, bent on imposture, made a pact with his mother which implies her literacy:

"Pythagoras, on coming to Italy, made a subterranean dwelling and

enjoined on his mother to mark and record all that passed, and at what

hour, and to send her notes down to him until he should ascend. She did

so." (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Volume II,

Book VIII, Chapter 1, 41).

The underground sojourn became part of the discipline imposed on

the postulant: ". . .he imitated it and himself also taught his

disciples to be silent, and obliged the student to remain quietly in

rooms underneath the earth." (A Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library,

Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie, Kindle location 6362, quote from Hippolytus

of Rome, Refutation of All Heresies, Book I, Chapter 2). If there is factual

basis to the story, then his mother was literate. At any rate, Diogenes

thinks it plausible that she may have been, so much so at least as

to make it worthwhile to repeat the story.

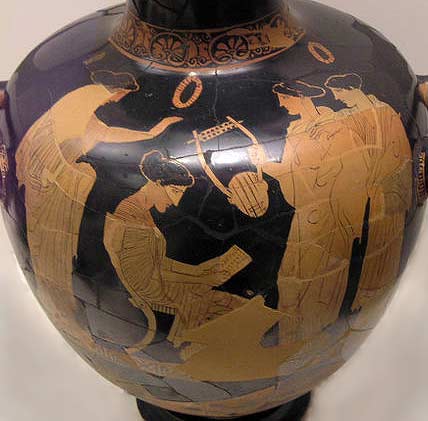

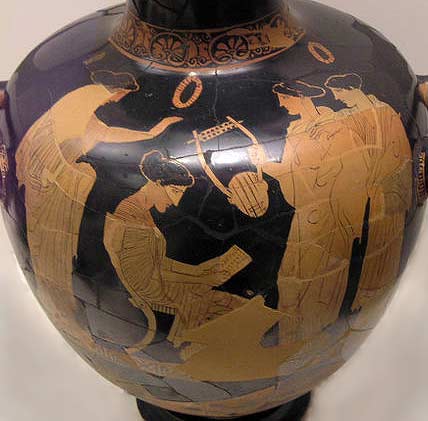

He also evidently attracted women converts. According to his biographer Iamblichus, Pythagoras lectured to women in the temple of Juno in Crotona.

Evidently he made an impact: "But through this praise pertaining to

piety, Pythagoras is said to have produced so great a change in

female attire, that the women no longer dared to clothe themselves

with costly garments, but consecrated many myriads of their

vestments in the temple of Juno." (p. 26, Iamblichus, Life of

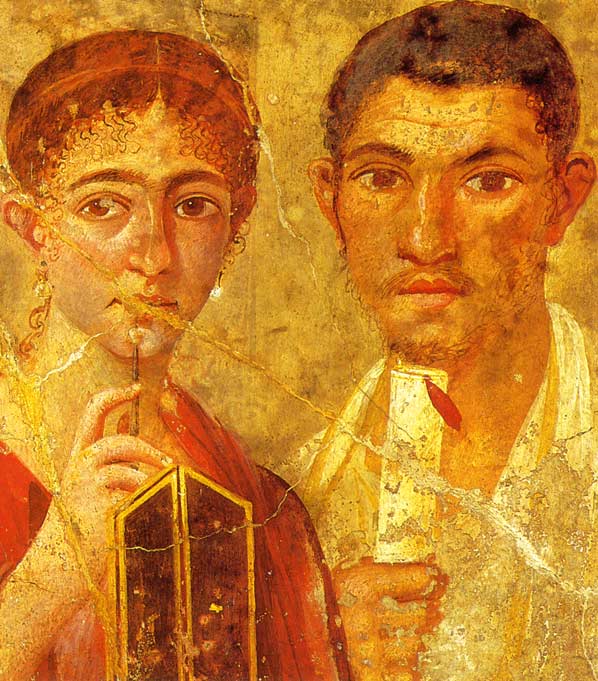

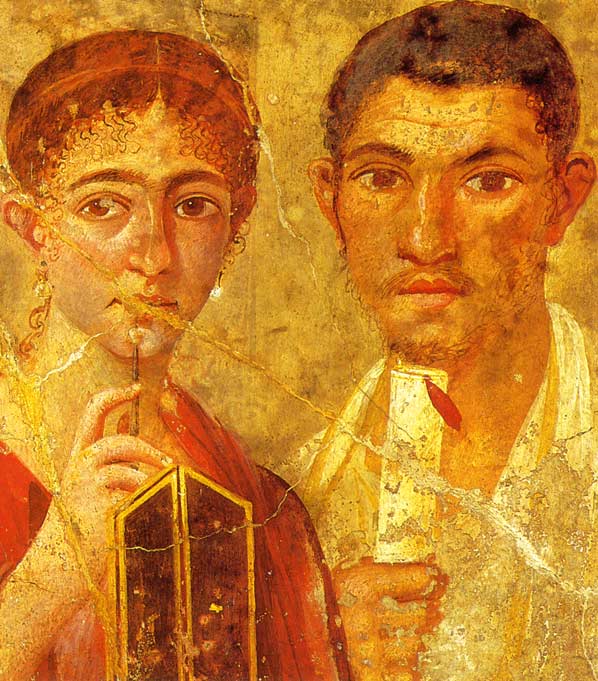

Pythagoras, Chapter XI). A female disciple named Theano wrote philosophical treatises, or at any rate such were attributed

to her:

"Moreover, some say that Phanothea, the wife of Icarius, invented

the heroic hexameter; others Themis, one of the Titanides. Didymus, however,

in his work On the Pythagorean Philosophy, relates that Theano of Crotona

was the first woman who cultivated philosophy and composed poems."

(Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, Miscellanies, Book 1, Chapter 16).

Theano is sometimes stated to be Pythagoras' wife; whether the

writing Theano was his wife, or was some other party, perhaps named

after her, is unclear. Clement quotes Theano, "For the Pythagorean Theano writes, 'Life

were indeed a feast to the wicked, who, having done evil, then die;

were not the soul immortal, death would be a godsend.'" (Clement of

Alexandria, Stromata, Book IV, Chapter VII). There is a tendency in

religious sects for names to be recycled: just think of how many

'Muhammad's' and 'Fatima's' there are, in circles devoted to

following the unlettered Arabian prophet. The writing Theano may

thus have been a disciple of the next generation. The Pythagoreans

became notorious for forging later writings under the names of earlier

dignitaries; still one cannot rule out the possible existence of an

'historical Theano.'

According to Clement, Theano had a daughter, Myia, who was also

educated in the Pythagorean philosophy:

"Themisto too, of Lampsacus, the daughter of Zoilus, the wife of

Leontes of Lampsacus, studied the Epicurean philosophy, as Myia the

daughter of Theano the Pythagorean, and Arignote, who wrote the

history of Dionysius. And the daughters of Diodorus, who was called

Kronus, all became dialecticians, as Philo the dialectician says

in the Menexenus, whose names are mentioned as follows —

Menexene, Argia, Theognis, Artemesia, Pantaclea." (Clement of

Alexandria, Stromata, Book IV, Chapter XIX).

At its best, Pythagorean ethics can ascend nearly to the heights

of Christianity: "Such as you wish your neighbor to be to you, such

also be to your neighbors." (Sentence 20, Sentences of Sextus the

Pythagorean; since there is no evidence of this treatise existing

prior to the Christian era, it is not really a prefiguring of the

Golden Rule). At its lowest, however, it reflects confusion about beans. The

sect produced its own body of literature. There survives a Pythagorean treatise, 'On the Harmony of Women,' whose stated author is Perictyone, a female name,

also 'On Woman's Temperance,' whose stated author is Phyntis,

Daughter of Callicrates. Pythagoras' sect flourished for some

centuries, attracting many converts, but then fell on hard times, at least

as a communal, self-perpetuating fellowship,

although some of their tenets were revived by Plato and others. It is

customary for critics to deny that the treatises in the Pythagorean

corpus were written by their stated authors, but the forger's choice is not

likely to have fallen on people who were non-existent in the first

place. It is common for religious sects to recycle the names of the founding

generation; think of all the Muslim 'Fatima's' and Christian

'Mary's.' While it is not now possible to unravel who some of these people

were, there were evidently literate, treatise-writing women within

the Pythagorean ranks. If the skeptic says there were not, he must also

explain why they kept making them up.

Leontion

Epicurus the philosopher is reported to have written letters to Leontion

the courtesan and to Themista, the wife of a disciple:

"Also that in his letters he wrote to Leontion, 'O Lord Apollo, my

dear little Leontion, with what tumultuous applause we were inspired as

we read your letter.' Then again to Themista, the wife of Leonteus: 'I

am quite ready, if you do not come to see me, to spin thrice on my own

axis...'" (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Volume II, Book X, 5)

Diogenes, an Epicurean, waxes indignant at these reports and seeks to discredit

them, although he concedes these women were part of Epicurus' social circle.

Whether or not the philosopher who made pleasure the end of life corresponded

with courtesans, these reports cannot have originated in a social milieu

in which women were assumed illiterate and incapable of assimilating private correspondence.

Some people say: a.) it is a known fact that virtually all Greek

women were illiterate, however b.) there are courtesans like

Leontion known to be literate; therefore c.) the Greeks must have

nurtured an institution like the Japanese Geisha, whose handlers

caused them to be educated to enhance their value as high-priced

prostitutes. No Greek author, however, is aware of any such

institution or set of circumstances. Let us rather examine premise

a.). Is it really known that virtually all Greek women were

illiterate? What Greek author ever says so? Why allow an exception

for those few women employed as courtesans while continuing to sweep

the massive collection of literate Greek women who were not

courtesans under the rug? Premise a.) is not fact but fiction. Women

like Leontion likely acquired their education in childhood before

making the life choices which resulted in their chosen profession.

Greek culture put its stamp upon a wide swath of the ancient world

in consequence of the Macedonian conquests. To judge by facts rather

than one-size-fits-all templates, it seems Greek women of affluent

background were often literate; however, this presumption of

literacy does not descend as low down the social scale for women as

it does for men. There is a presumption in Greek society that

free-born males ought to be educated; but a middle class family

willing to scrimp and save so that Junior could be educated was not

often willing to make a comparable sacrifice for his sister.

Telesilla

"Above the theater stands a sanctuary of Aphrodite. In front of the

goddess's place Telesilla, the composer of the songs, has been carved on

a slab of stone; her books are thrown about at her feet; she is looking

at a helmet she has in her hand and is going to put on. Telesilla was a

very famous woman and a distinguished poet." (Pausanias, Guide to

Greece, Volume 1, Book II, Corinth and the Argolid, 20.7)

Pausanias quotes verses by Telesilla, so evidently there remained poetry

circulating under her name. Plutarch mentions her also:

"Of all the deeds performed by women for the community

none is more famous than the struggle against Cleomenes for Argos,

which the women carried out at the instigation of Telesilla the

poetess. She, as they say, was the daughter of a famous house but

sickly in body, and so she sent to the god to ask about health; and

when an oracle was given her to cultivate the Muses, she followed

the god's advice, and by devoting herself to poetry and music she

was quickly relieved of her trouble, and was greatly admired by the

women for her poetic art." (Plutarch, On the Bravery of Women,

Chapter IV, The Women of Argos).

Evidently she treated mythological themes; Apollodorus cites her

version the tale of Niobe, Amphion's wife, who incurred Latona's

jealous anger by boasting of her many children:

"But according to Telesilla there were saved Amyclas and

Meliboea, and Amphion also was shot by them [Artemis and Apollo]."

(Apollodorus, The Library, Book III, v. 6-7, Loeb p. 343).

Perhaps she wrote about a pet nightingale, if Martial refers to the

ancient poetess in saying, ". . .if Telesilla has set up a monument over

her nightingale. . ." (Martial, Epigrams, Book VII, LXXXVII, Kindle

location 4304). According to Clement of Alexandria, she seems also to

have produced martial and patriotic poetry: "And they say that the Argolic women, under the guidance of Telesilla the poetess, turned to

flight the doughty Spartans by merely showing themselves; and that she

produced in them fearlessness of death." (Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, Book IV, Chapter 13).

Another female poet Pausanias mentions is

"Moiro of Byzantium, who composed epic and elegiac verse"

(Pausanias, Guide to Greece, Volume 1, Book IX, Boiotia, 5.4).

Megisto

The tyrant Aristotimus, according to Plutarch, desired the women he had treacherously imprisoned to

write letters urging their freedom-fighter husbands to desert the cause. Why did he make such a request,

futile as it turned out? Had no one told him women in antiquity were illiterate?

"Aristotimus, alarmed at this, went to see the imprisoned women, and, thinking that he should accomplish his purpose better by fear than by favor, he gave orders to them to write and send letters to their husbands so that the men should leave the country; and if they would not write, he threatened to put them all to death after torturing them and making away with their children first. As he stood there a long time and urged them to say whether they would carry out any

part of this programme, most of the women made no answer to him, but looked at one another in silence, and showed by nods that all their minds were made up not to be frightened or perturbed at the threat. Megisto, the wife of Timoleon, who, on account of her husband and her own virtues as well, held the position of leader, did not think it meet to rise, nor would she allow the other women to do so; but, keeping her seat, she made answer to him:

'If you were a sensible man, you would not be talking to women about husbands, but you would send to them, as to those having authority over us, finding better words to say to them than those by which you tricked us. But if you despair of persuading them yourself,

and are attempting to use us to mislead them, do not expect to deceive us again, and I pray that they may never entertain such a base thought that, to spare their wives and little children, they should forsake the cause of their country's freedom.'"

(Plutarch, On the Bravery of Women, XV. Micca and Megisto).

Plutarch mentions an uncharacteristic sally of gallantry on the part of the Athenians, who refrained from

opening Philip of Macedon's letters to his wife, thinking these should be private:

"And I do not believe that the Thebans either, if they

had obtained control of their enemies' letters, would have refrained

from reading them, as the Athenians, when they captured Philip's

mail-carriers with a letter addressed to Olympias, refrained from

breaking the seal and making known an affectionate private message

of an absent husband to his wife." (Plutarch, Moralia, Precepts of

Statecraft, Complete Works of Plutarch, Kindle location 55054).

How could this principle, that communications between husband and wife, ever have

occurred to anyone, if the wife was always obliged to find someone to read it to her?

Plutarch also reports Alexander reading a "confidential" letter from

Olympias: "Once when he was reading a confidential letter from his

mother, and Hephaestion, who, as it happened, was sitting beside him,

was quite openly reading it too, Alexander did not stop him, but merely

placed his own signet-ring on Hephaestion's lips, sealing them to

silence with a friend's confidence." (Plutarch, Moralia, On the Fortune

or Virtue of Alexander, Book I, Chapter 11, Complete Works of Plutarch, Kindle

location 41595). But if the 'scholars' of the Jesus Publishing Industry

are right, there can be no such thing as a "confidential" letter from a

woman.

Polycrite

There was a war going on between the Naxians and Milesians, and

the Erythraeans were allied with the Milesians. Polycrite managed to

sneak a message to her people. How, if she was illiterate?

"Diognetus, the general of the Erythraeans, entrusted with the command of a stronghold, its natural advantages reinforced by fortification to menace the city of the Naxians, gathered much spoil from the Naxians, and captured some free women and maidens; with one of these, Polycrite, he fell in love and kept her, not as a captive, but in the status of a wedded wife. Now when a festival which the Milesians celebrate came due in the army, and all turned to drinking and social gatherings, Polycrite asked Diognetus if there were any reason why she should not send some bits of pastry to her

brothers. And when he not only gave her permission but urged her to do so, she slipped into a cake a note written on a sheet of lead, and bade the bearer tell her brothers that they themselves and no others should consume what she had sent. The brothers came upon the piece of lead and read the words of Polycrite, advising them to attack the enemy that night, as they were all in a state of carelessness from drink on account of the festival. Her brothers took this message to their generals and strongly urged them to set forth with themselves."

(Plutarch, On the Bravery of Women, XVII, Polycrite).

Corinna

Another woman poet reportedly won a prize in competition with Pindar, though

Pausanias grouses it must have been her dialect that won, not her poems:

"The memorial of Korinna, the only Tanagran composer of songs, is

at a conspicuous point of the city; in the training-ground there is a picture

of Corinna tying her hair with a ribbon for the victory she won over Pindar

at Thebes." (Pausanias, Guide to Greece, Volume 1, Book IX, Boetia, 22.3)

She reviewed Pindar's poems:

"Which admonition Pindar laying up in his mind, wrote a certain ode which thus begins:

"Shall I Ismenus sing,

Or Melia, that from spindles all of gold

Her twisted yarn unwinds,

Or Cadmus, that most ancient king. . .

"Which when he showed to Corinna, she with a smile replied: When you sow, you must scatter the seed with your hand, not empty the whole sack at once."

(Plutarch, Whether the Athenians were more Renowned for their Warlike

Achievements or for their Learning, The Morals, Volume 5, Section 4).

The first century Latin poet Statius mentions her in a eulogy for his departed school-teacher father,

who evidently held her poetry in high regard:

"Hence came it that thou wert trusted with the fond hopes of

parents, and under thy guidance noble youths were ruled, and

learnt the ways and the prowess of men of old—the fate of

Troy, Ulysses' tardy return, what power has Maeonides to

describe in song the battles and steeds of heroes, how the

bards of Asera and of Sicily enriched the faithful husbandman,

the law that sways the recurrent, winding rhythms of Pindar's

lyre, Ibycus who besought the birds, Alcman whose strains

warlike Amyclae sang, proud Stesichorus, and bold Sappho who

feared not Leucas, but took the heroic leap, and all others

whom the harp has deemed worthy. Skilled were thou to expound

the songs of Battus' son [Callimachus], and the dark ways and

straitened speech of Lycophron, and Sophron's tangled mazes and

the hidden thought of subtle Corinna." (Statius, Sylvae,

Book V, III, lines 146-158, p. 317 Loeb edition).

Praxilla

"Praxilla, the Sicyonian poetess, was also celebrated for the composition

of scholia." (Athenaeus of Naucratis, The Banquet of the learned of AthenŠus, Volume III , Book XV, 49).

Only a scattering of fragments of this woman's literary output

remain, which is understandable if this memorial of Adonis is

typical: "Finest of all the things I have left is the light of the

sun, Next to that the brilliant stars and the face of the moon,

Cucumbers in their season, too, and apples and pears." Cucumbers?

This verse, according to Zenobius, was the basis for the proverbial

expression, "sillier than Praxilla's Adonis." Nevertheless, she must

have been literate. Tatian thought little of her poems:

"For Lysippus cast a statue of Praxilla, whose poems

contain nothing useful, and Menestratus one of Learchis, and

Selanion one of Sappho the courtesan, and Naucydes one of Erinna the

Lesbian, and Boiscus one of Myrtis, and Cephisodotus one of Myro of

Byzantium, and Gomphus one of Praxigoris, and Amphistratus one of

Clito. And what shall I say about Anyta, Telesilla, and Mystis? Of

the first Euthycrates and Cephisodotus made a statue, and of the

second Niceratus, and of the third Aristodotus; Euthycrates made one

of Mnesiarchis the Ephesian, Selanion one of Corinna, and

Euthycrates one of Thalarchis the Argive." (Tatian, Address to the

Greeks, Chapter 33).

Tatian brings these considerations up, not as an unprovoked

attack against the pagans, but in answer to their charge that

Christian assemblies include women: "You who say that we talk

nonsense among women and boys, among maidens and old women, and

scoff at us for not being with you, hear what silliness prevails

among the Greeks." (Tatian, Address to the Greeks, Chapter 33). This

misogynistic charge against the Christians was a frequent resort of

anti-Christian polemicists.

The Myrtis he mentions was known also to Plutarch: "And when

Colonus had given judgment, Ochne's brothers were banished, and she

threw herself from a precipice, as Myrtis, the lyric poetess of

Anthedon, has related." (Plutarch, Moralia, Greek Questions, Chapter

40, Complete Works of Plutarch, Kindle location 40669).

|