|

Not only could Jesus read, many read about him, "Now Pilate wrote a title and put it on the cross. And the writing was: JESUS OF NAZARETH, THE KING OF THE JEWS.

Then many of the Jews read this title, for the place where Jesus was crucified was near the city; and it was written in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin."

(John 19:19-20). John does not say that many saw the title but were

unable to read it, but that many read the title. The striking confession in

this title may have been intended only in mockery by Pilate, but is

nonetheless true to the letter.

Flavius Josephus

Flavius Josephus is a morally ambiguous character who at one time

held the leadership of the Jewish resistance to Roman rule in Galilee.

By his own account, however, he was not trying too hard to accomplish

his mission. His Judaism, which centered around hereditary priesthood

and the temple, is so totally extinct that people today cannot really

grasp his point of view. Those who want to put a red beret atop the

heads of the deceived deceivers of the day, and pose it at a jaunty Che

Guevara angle, cannot abide his dislike of these 'freedom fighters,'

whose achievement in the end resembles more that of Jim Jones of

Jonestown than of George Washington. One thing worth noting, regardless, is that he was

a talented youngster who received encouragement from everybody:

"I was myself brought up with my brother, whose

name was Matthias, for he was my own brother, by both father and

mother; and I made mighty proficiency in the improvements of my

learning, and appeared to have both a great memory and

understanding. Moreover, when I was a child, and about fourteen

years of age, I was commended by all for the love I had to learning;

on which account the high priests and principal men of the city came

then frequently to me together, in order to know my opinion about

the accurate understanding of points of the law; and when I was

about sixteen years old, I had a mind to make trial of the several

sects that were among us." (Life of Flavius Josephus, Chapter 2, p.

1, The Complete Works of Josephus).

I don't suppose the learned men felt they needed to know his

opinion, but they made a fuss over him anyway. This is not

characteristic of the 'agrarian' societies envisaged by the Jesus

Seminar. If only a tiny elite perched atop the population can ever

become literate, a huge amount of talent must of necessity go to

waste, and who could ever invest any energy in regret? Fussing over

a talented child is the kind of thing the ancient Romans used to do,

and. . .oh, I'm forgetting they were almost entirely illiterate too.

One interesting fact Josephus records about the Jewish rebellion,

is the zealots' revival of the ancient practice of filling offices

by casting lots,

"Hereupon they sent for one of the pontifical tribes,

which is called Eniachim, and cast lots which of it should be the

high priest. By fortune the lot so fell as to demonstrate their

iniquity after the plainest manner, for it fell upon one whose name

was Phannias, the son of Samuel, of the village Aphtha. He was a man

not only unworthy of the high priesthood, but that did not well know

what the high priesthood was, such a mere rustic was he!" (Josephus,

Wars of the Jews, Book IV, Chapter 3, Section 8).

Whether assigning office by lot is a good idea or a bad idea, it is

clear from Josephus' contempt for Phannias, which he expects the reader

to share, that it was not taken for

granted at the time that a priest should be anything other than a

learned man. This attitude is commonly expressed in the literature of a

day; the apocryphal testament of Levi instructs,

"So now, my sons, teach writing and discipline and

wisdom to your children, so that wisdom may be their perpetual

glory, for the one who learns wisdom shall have glory through it.

But whoever disdains wisdom becomes an object of scorn. Consider, my

sons, my brother Joseph, who teaches writing and discipline and

wisdom." (The Words of Levi, Dead Sea Scrolls, Michael Wise, Martin Abegg, Jr., and Edward Cook, p. 257).

It is understandable that the Levites, the teachers of Israel, should

teach "writing" to their children, because it is an acquired skill

without which they cannot do their assigned job;

it is less understandable how people like Bart Ehrman can expect to get

away with assigning a literacy rate of 1 or 2 per cent to first century

Israel. While exhortation is one thing and acquisition another, the reader

should note the futility of exhorting people to acquire a skill to

which only a tiny percentage were born entitled, in their imagined 'agrarian

society.'

Court Clerks

While the evidence of the Talmud comes from a later period, courts were expected to have clerks, just

like our courts:

"Then, a further two clerks, two sheriffs, two litigants, two witnesses, two zomemim, and two to refute the zomemim, gives a hundred and fourteen in all. Moreover, it has been taught: A scholar should not reside in a city where the following ten things are not found: A court of justice that imposes flagellation and decrees penalties; a charity fund collected by two and distributed by three; a Synagogue; public baths; a convenience; a circumciser; a surgeon, a notary; a slaughterer and a school-master."

(Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin, 17b.)

Why? To make note of the proceedings, presumably.

Masada

To judge the social dynamics of the Jewish Revolt by Josephus'

account, the ranks of the insurgents were not filled with the wealthy,

most of whom either sympathized with or were resigned to Roman

sovereignty. So the Sicarii who gathered, and died, at Masada are not

likely to belong to the top tier economically. Were they literate? The

archaeological record shows that some certainly were. People in

antiquity used broken pottery shards as a kind of free and plentiful

note-paper, and fortunately they stand up to weathering better than do

other writing materials.

"The greatest number of ostraca comes from Masada, all

assigned to the time of the First Revolt. They are brief, some

extremely brief, messages; over two dozen require the issue of bread

on specific days to named individuals, some others are five or six

lines long, one pleading for repayment of a debt.. . .Names were

also painted on pottery vessels to mark ownership, such as Joseph,

Johanan (=John), Saul, while on other pots were notes of their

contents, 'pressed dates,' 'fish,' 'dough.'" (Alan Millard, Reading

and Writing in the Time of Jesus, pp. 94-96).

Some of Masada's defenders were bilingual, giving orders in

Greek,

"Ostraca may withstand the elements better than papyri,

although the ink may be washed off, and, in fact, some 20 Greek

ostraca were uncovered on Masada and attributed to the period of the

First Revolt (66-73/4). They are brief orders for supplying wheat or

barley, such as 'Give seven measures of wheat to the donkey drivers,

for baking' (or 'for the kitchen'), lists of names with sums of

money beside them, single names and letters of the alphabet in

order." (Alan Millard, Reading and Writing in the Time of

Jesus, p. 116)

Who were the people expected to give grain to the donkey drivers?

The upper crust of society?

The record of Jewish literacy on broken pottery goes back to

pre-exilic times,

"Another piece of evidence of the time is an ostracon

found at Mesad Hashavyahu, a small fort near Yavneh-Yam on the

coast. It is a letter of a wronged peasant to the officer of the

fort, and it shows how the social laws of the Bible were reflected

in contemporary life during the reign of Josiah. (Archaeology of the

Bible: Book by Book, by Gaalyah Cornfeld and David Noel Freedman, p.

134)

How striking that a wronged peasant, at this early date, could find the means to petition his

government for a redress of grievances!

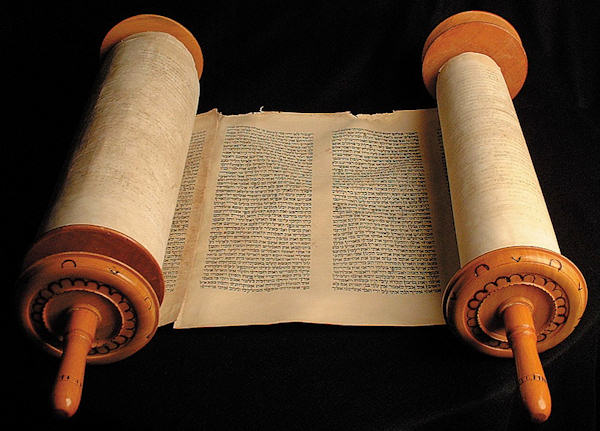

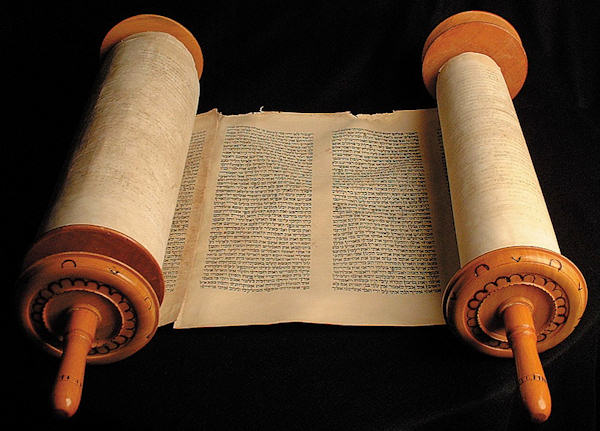

Reader's Digest

Is it permissible to prepare a scroll containing excerpts from the Law for the edification of young

scholars? The Rabbis are of two minds on this point:

"Abaye asked Rabbah: Is it permitted to write out a scroll [containing a passage] for a child to learn from? This is a problem alike for one who holds that the Torah was transmitted [to Moses] scroll by scroll, and for one who holds that the Torah was transmitted entire. It is a problem for one who holds that the Torah was transmitted scroll by scroll: since it was transmitted scroll by scroll, may we also write separate scrolls, or do we say that since it has all been joined together it must remain so? It is equally a problem for one who holds that the Torah was transmitted entire: since it was transmitted entire, is it improper to write [separate scrolls], or do we say that since we cannot dispense with this we do write them? — He replied: We do not write. What is the reason? — Because we do not write."

(Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Gittin 60a).

The concept being, since God delivered it as a unit, so it must remain, lest we add to or subtract from scripture.

What is clear is that there was a demand: somebody wanted to prepare such

scrolls to facilitate childhood education. And some Rabbis saw no

problem with such excerpts:

"On this point Tannaim differ [as we were taught]: 'A

scroll should not be written for a child to learn from; if, however,

it is the intention of the writer to complete it, he may do so. R.

Judah says: He may write from Bereshith to [the story of the

generation of the] Flood, or in the Priests' Law up to, And it came

to pass on the eighth day.'" (Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Gittin

60a).

Some of the Rabbis point out that the Torah must have occupied

multiple scrolls from its first writing down, as indeed must have

been the case.

Rabha

In the Babylonian Talmud, a speaker identified only as Rabha explains that male

literacy was near-universal in his day, not like in "ancient times:"

"GEMARA: Rabha said: Great Halakhoth can be inferred

from the custom of saying Hallel: From the custom of our time, when

almost all men can read the Hallel themselves, nevertheless they

repeat the beginnings of the chapters after the reader, we may infer

what are the essential portions of Hallel, and how it was done in

the ancient times, when the people could not read themselves, and a

man was wanted to read it, for them to repeat after him."

(The Babylonian Talmud, edited by Michael L. Rodkinson, Volume VII,

Section Moed, Tract Succah, Chapter III, Kindle location 29463).

This same tractate goes on to identify "Rabha" as a contemporary of

Abayi; they hold a conversation: "Abayi said to Rabha: Why do we use

the Lulab all the seven days. . .Rabha answered: We use the willow tied

with the Lulab together all the seven days. Rejoined Abayi: But we use

it not for the sake of the willow. . ." (The Babylonian Talmud, edited

by Michael L. Rodkinson, Volume VII, Section Moed, Tract Succah, Chapter IV, Kindle location 29658). This

brings us to the third-fourth century A.D., rather far from our period

of interest; still, knowing that Jews had achieved universal male

literacy by this period should serve as a brake to assumptions of

universal illiteracy a few centuries prior.

Looking back to the first and second centuries, it was certainly

not impossible for an adult male to be illiterate; Rabbi Akiba was

illiterate up until middle age:

"For how did R. Aqiba begin his wonderful career? (Was

it not in the manner hinted in the above words?) It has been said

that when he was forty years old he had not learned yet anything.

(At that age however, he conceived the idea of applying himself to

study.). . .He at once turned to the study of the Law. He and his

son went to a school were children were instructed, and addressed

one of the teachers: 'Master, teach me Torah.' Aqiba and his son

took hold of the slate, and the teacher wrote upon it the alphabet,

and he quickly learned it; and then wrote it in the reversed order,

and learned as fast; then he learned the Book of Leviticus, and

proceeded from one book to the other, until he finished the study of

the Bible." (The Babylonian Talmud, edited by Michael L. Rodkinson,

Volume 9, Tract Aboth, Chapter I, Kindle location 37164).

So male illiteracy was still possible; still, the percentage cannot have been

as represented, because, just as you cannot turn the Queen Mary in a

tight radius, so you cannot change a huge social variable like literacy

in a heartbeat. In the tractate touching on oaths, there seems an

assumption of universal schooling,

"Said Abayi: Rabbi holds that elementary knowledge is

considered, i.e., the knowledge one learns in school when yet a

child (e.g., he learned that he who toucheth an unclean thing

becomes defiled). Said R. Papa to him: According to this theory, how

can we find a case in which he was unaware before? And he answered:

It may be found with him who was captured by heathens while he was

still an infant, and was brought up by them." (The Babylonian

Talmud, edited by Michael L. Rodkinson, Volume 17, Tract Shebuoth,

Chapter 1, Kindle location 68265).

If, to discuss a hypothetical unschooled person, one must theorize about someone kidnapped by heathen,

then it seems like the goal was ultimately achieved! The goal, while yet

unachieved, cannot have been unheard of or unthought of, even in our

earlier period.

Outliers

There have always been illiterates: "And the book is delivered to

him that is not learned, saying, Read this, I pray thee: and he saith,

I am not learned." (Isaiah 29:12). Entire population groups have been

neglected. What about women's literacy? Unfortunately it lagged throughout

this period; however the situation was by no means as bleak as is

sometimes represented. The situation amongst the Jews mirrored

that in the larger society: "Before passing to an account of elementary

schools, it may be well, once and for all, to say that the Rabbis did

not approve of the same amount of instruction being given to girls as

to boys. . .The unkindest thing, perhaps, which they said on this score

was, 'Women are of a light mind;' though in its oft repetition

the saying almost reads like a semi-jocular way of cutting short a

subject on which discussion is disagreeable." (Alfred Edersheim,

Sketches of Jewish Social Life in the Days of Christ, p. 103). They were

unsympathetic, sometimes aggressively so: "He answered her: There is no

wisdom in woman except with the distaff." (Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Yoma, 66b.):

|