|

Centuries before, the pagan poet Ovid had hoped for no more than a humble

readership for his plaints from exile on the Black Sea; he understood he

was out of favor with the power elite: "Therefore

be careful, my book, and look all around with timid heart, so as to

find content in being read by ordinary folk." (Ovid, Tristia, Book

I, Chapter I) [ergo caue, liber, et timida circumspice mente, ut satis a media sit tibi plebe legi.]". The problem is not that

the information is unavailable, rather that they won't believe it.

Alexander of Abonoteichus

The satirist Lucian of Samosata tells the story of Alexander of

Abonoteichus, a canny and shrewd false prophet. Trained in the tricks of the trade by no less than a

disciple of the great man Apollonius of Tyana, Alexander sets up shop in

Paphlagonia with his pet snake to fleece the gullible populace. He

urges them to make their queries to him in writing, securely sealed:

“When it was time to carry out the purpose for which the whole scheme had been concocted—that is to say, to make predictions and give oracles to those who sought them—taking his cue from Amphilochus in Cilicia, who, as you know, after the death and disappearance of his father Amphiaraus at Thebes, was exiled from his own country, went to Cilicia, and got on very well by foretelling the future, like his father, for the Cilicians and getting two obols for each prediction—taking, as I say, his cue from him, Alexander announced to all comers that the god would make prophecies, and named a date for it in advance. He directed everyone to write down in a scroll whatever he wanted and what he especially wished to learn, to tie it up, and to seal it with wax or clay or something else of that sort. Then he himself, after taking the scrolls and entering the inner sanctuary—for by that time the temple had been erected and the stage set—proposed to summon in order, with herald and priest, those who had submitted them, and after the god told him about each case, to give back the scroll with the seal upon it, just as it was, and the reply to it endorsed upon it; for the god would reply explicitly to any question that anyone should put.

“As a matter of fact, this trick, to a man like you, and if it is not out of place to say so, like myself also, was obvious and easy to see through, but to those drivelling idiots it was miraculous and almost as good as incredible. Having discovered various ways of undoing the seals, he would read all the questions and answer them as he thought best. Then he would roll up the scrolls again, seal them, and give them back, to the great astonishment of the recipients, among whom the comment was frequent:

'Why, how did he learn the questions which I gave him very securely sealed with impressions hard to counterfeit, unless there was really some god that knew everything?'”

(Lucian of Samosata, Alexander the False Prophet, Chapters

19-20).

Now if in fact these gullible rubes had gone to Kinko's for

their sealed scrolls, then wouldn't their obvious resort have

been, 'No wonder he knows what the scroll says, he must have

paid off that desk clerk at Kinko's.' Isn't it apparent, rather,

that literacy must have been widespread? Not universal;

Alexander was charging good money for these prophecies, a

drachma and two obols; the "everyone" directed to write his

questions on the sealed scrolls cannot have included slaves with

no cash income, nor laborers with very small incomes. But

neither does it show literacy restricted to the one-percenters,

as imaginatively reconstructed by the Jesus Publishing Industry. He

somewhere describes the inhabitants of Paphlagonia, thusly: ". .

.with brogans on their feet and breaths that reeked of garlic,"

which doesn't sound like the one-percenters to me.

Believe it or Not

The story goes, an African tribe told a German anthropologist they had no

knowledge of any link between sex and procreation. He dutifully noted down this

fact in his notebook and went on his way, no doubt

intending to publish in the scholarly journals this startling

revelation. An English trader standing by protested, 'Why did you

tell that man that?' The tribes-people replied, 'Oh, we just wanted

to see if it's true what people say, that those Germans will believe

anything.'

Some people say that, even though modern educators understand the

synergy between reading and writing, it had not yet been

discovered in the ancient world. Because educators in antiquity did

not understand the connection between these two skills, they instead

taught them separately, and consequently many could read who could not write at all.

"Today we learn reading and writing together. . .But that's because

of the way we have set up our educational system. There is nothing

inherent in learning to read that can necessarily teach you how to

write." (Bart D. Ehrman, Forged, pp. 71-72). Is

this what the ancient educators themselves say?:

"But these precepts of oratory, though necessary to be

known, are yet insufficient to produce the full power of

eloquence, unless there be united with them a certain efficient

readiness, which among the Greeks is called εξις, "habit," and

to which I know that it is an ordinary subject of inquiry

whether more is contributed by writing, reading, or speaking.

This question we should have to examine with careful attention,

if we could confine ourselves to any one of those exercises; 2. but they are all so connected, so inseparably linked,

with one another, that if any one of them be neglected, we

labor in vain in the other two; for our speech will never

become forcible and energetic, unless it acquires strength from

great practice in writing, and the labor of writing, if left

destitute of models from reading, passes away without effect,

as having no director; while he who knows how everything

ought to be said, will, if he has not his eloquence in readiness, and prepared for all emergencies, merely brood, as it

were, over locked up treasure." (Quintilian, Institutes of Oratory, Book

X, Chapter 1).

Aristotle, in examining the fitness of various definitions, considers the possibility

that someone might define 'grammar' as the ability to write (how

could he have known?!):

"Moreover, see if, while the term to be defined is used in relation to many things, he has failed to render it in relation

to all of them; as (e.g.) if he define ‘grammar’ as the ‘knowledge how to write from dictation’: for he ought also to say

that it is a knowledge how to read as well. For in rendering it as ‘knowledge of writing’

he has no more defined it than by rendering it as ‘knowledge of

reading’: neither in fact has succeeded, but only he who mentions

both these things, since it is impossible that there should be more

than one definition of the same thing." (Aristotle,

Topics, Book VI, Chapter 5).

He does not say, 'this definition is very natural, because we all

know many who can read and not write,' rather

he finds the definition defective in that it omits mention of the

matching skill.

The unknown author of the Latin treatise 'On Rhetoric to

Herennius' simply announces that those who know the alphabet can

both read and write:

"Those who know the letters of the alphabet can thereby

write out what is dictated to them and read aloud what they have

written." (Rhetorica ad Herennium, Book III, Chapter 17).

If there is supposed to have been a disconnect between these two

skills in antiquity, why did its discovery await modern times? Perhaps

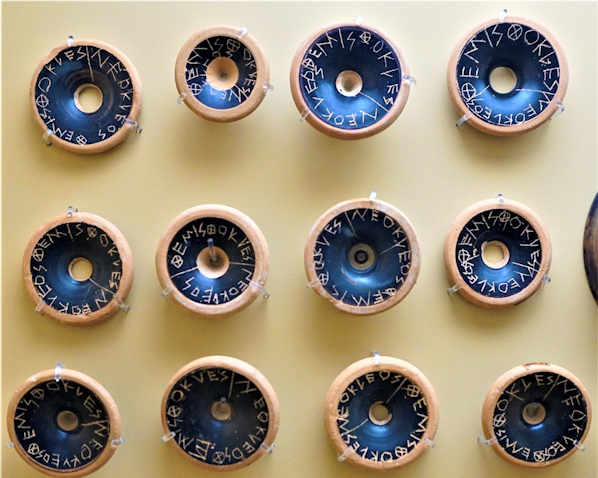

they hope to take away the sting of the popularity of alphabetic

riddles and games in antiquity, which would otherwise testify to

widespread literacy. As the curtain is coming down on the world of

classical antiquity, Procopius mentions an alphabetic riddle popular

in newly liberated Carthage:

"And they said that an old oracle had been uttered by the

children in earlier times in Carthage, to the effect that "gamma

shall pursue beta, and again beta itself shall pursue gamma." And at

that time it had been spoken by the children in play and had been

left as an unexplained riddle, but now it was perfectly clear to

all. For formerly Gizeric had driven out Boniface and now Belisarius

was doing the same to Gelimer. This, then, whether it was a rumour

or an oracle, came out as I have stated."

(Procopius of Caesarea. The Complete Procopius Anthology: The Wars of

Justinian, The Secret History of the Court of Justinian, The

Buildings of Justinian (Texts From Ancient Rome) (Kindle Locations

4266-4269). www.Bybliotech.org.)

Why would a purely illiterate populace take pleasure in such admittedly silly things?

Barbarians

The Roman Empire ranged from the North Sea to Arabia, and

included within its borders both the heirs to ancient civilizations

like the Egyptians, and also wild men who lived in the woods, like

the Germans and the Britons. The Spaniards at the time of the Roman conquest

had so little concept of 'going for a walk,' a civilized pleasure, they thought the Romans who did so

must be deranged: "The Vettones, the first time they came to a Roman

camp, and saw certain of the officers walking up and down the roads

for the mere pleasure of walking, supposed that they were mad, and

offered to show them the way to their tents. For they thought, when

not fighting, one should remain quietly seated at ease." (Strabo,

Geography, Book III, Chapter IV, Section 16, p. 246). The Romans

began the educational process:

"But most of all were they captivated by what he did

with their boys. Those of the highest birth, namely, he collected

together from various peoples, at Osca, a large city, and set over

them teachers of Greek and Roman learning; thus in reality he

made hostages of them, while ostensibly he was educating them,

with the assurance that when they became men he would give them a

share in administration and authority. So the fathers were

wonderfully pleased to see their sons, in purple-bordered togas,

very decorously going to their schools, and Sertorius paying their

fees for them, holding frequent examinations, distributing prizes to

the deserving, and presenting them with the golden necklaces which

the Romans call 'bullae'." (Plutarch Lives, Sertorius, Chapter 15).

Many evils came along with Roman imperialism, and patriots like

Queen Boudicca and Ariovistus saw no option but armed resistance. But there

was some good as well, including broad-based education, a

novelty to some folks. While this Oscan group were later reminded they were effectively

hostages, wherever Rome set down her boot on subject people's necks,

literacy rates rose, in some cases from zero. Within a few generations, the leading Latin grammarians

were coming out of Spain.

Literacy rates were low amongst some 'barbarians' even in the

presence of large populations and big cities. Strabo quoted Megathenes as witness to conditions amongst the inhabitants of

India, who could field a large army yet were: ". . .a people who

have no written laws, who are ignorant even of writing, and regulate

everything by memory." (Strabo, Geography, Book XV, Chapter 1,

Section 53, Volume III, p. 105). Apparently the individuals with whom this

witness was interacting were not literate. Literacy is sometimes imagined to be a

simple function of population or economic development, although this fantasy

cannot be confirmed by observation. Rather, certain polities set this as a

central desideratum, others do not.

The longer a place had been plugged into the system, the

more local conditions resembled those at Greece and Rome.

France's Mediterranean coast was so fully civilized that Marseilles,

originally a Greek colony, rivalled Athens as a magnet for

philosophy students:

"The aspect of the city at the present day is a proof of

this. For all those who profess to be men of taste, turn to the

study of elocution and philosophy. Thus this city for some little

time back has become a school for the barbarians, and has

communicated to the Galatae such a taste for Greek literature, that

they even draw contracts on the Grecian model. While at the present

day it so entices the noblest of the Romans, that those desirous of

studying resort thither in preference to Athens. These the Galatae

observing, and being at leisure on account of the peace, readily

devote themselves to similar pursuits, and that not merely

individuals, but the public generally; professors of the arts and

sciences, and likewise of medicine, being employed not only by

private persons, but by towns for common instruction." (Strabo,

Geography, Book IV, Chapter 1, Section 5, pp. 270-271).

It's interesting that these people drew contracts on the Greek model.

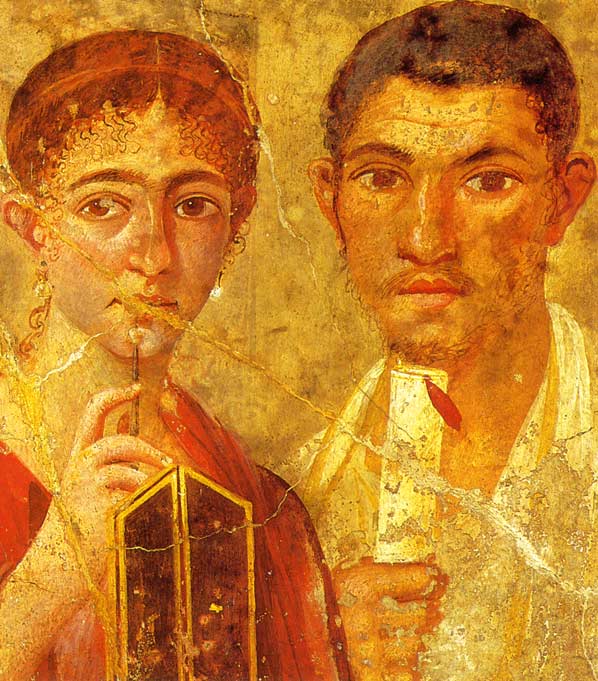

Aulus Gellius, summarizing a case that came before him as judge,

recapitulates the argument of a man against whom a monetary claim was made:

"Yet he, along with his numerous advocates, noisily protested that the

payment of the money ought to be shown in the usual way, by a receipt for

payment, by a book of accounts, by producing a signature, by a sealed deed,

or by the testimony of witnesses; and if it could be shown in none of these

ways, that he ought surely to be dismissed at once. . ." (Aulus Gellius,

Attic Nights, Book XIV, Chapter II). Why, in a society purportedly with 2-3%

literacy, do all the common ways of showing payment save one involve

writing?

Because its always best to get it in writing:

"Indeed, that one could not trust mere words about

friendship — for this is the only point remaining — is no doubt

clear. For it is absurd that, when lending money to one's

neighbours, no one would lightly put faith in word alone, but

instead requires witnesses and writings — and many do violence

to even these. . ." (Dio Chrysostom,

Discourse 74.27).

Balance

In the nineteenth century classicists idealized the civilization of Greece

and Rome. The classicists of that era were likelier to overstate ancient

literacy than to deny it. These optimists ignored substantial evidence

against universal literacy in the ancient world. There were certainly very

many illiterate persons, such as Justin describes:

"Among us these things can be heard and learned from persons who do not even know the

forms of the letters, who are uneducated and barbarous in speech, though wise and believing in mind; some,

indeed, even maimed and deprived of eyesight; so that you may understand that these things are not the effect

of human wisdom, but are uttered by the power of God."

(Justin Martyr, First Apology, Chapter 60).

Yet this modern correction, which emboldens secular Bible scholars to think

it plausible the gospel existed for decades only as oral tradition such

as might be heard amongst a South Seas tribe huddled around the fire, is

no correction at all. It falls overboard in the other direction, ridiculing

and rejecting almost all of what ancient authors say about who could, and

who could not, read and write. Why not credit their testimony?

Theory should be corrected to conform to facts, not facts trimmed to fit

theory. Marxist economics, in the experience of the many countries who

turned to this 'science' for guidance in managing their economies during

the twentieth century, cannot explain even the simplest of things such

as how to keep store shelves stocked with merchandise. Watching this 'science'

throw up its hands in bewilderment at buying and selling, and seeing its

expectations fail over and over in the last century, why would modern academics

trust so fervently in Marxism's predictive powers as to deny a recorded

fact: that free-born city-dwellers in classical antiquity were general

literate,— because this theory confesses itself unable to account for

the fact? Given this unsuccessful theory's many failed predications, why

not discard Marxist economics instead of discarding the ancient literacy

which it cannot explain?

To the Marxist, democracy is a dodge. But history shows that democracy

really is different. Ancient literacy first stirred in the cradle of democracy:

"Elementary education for all citizens was achieved early in Athens,

at least a century before Socrates, and literacy seems to have been widespread.

This reflected the rise of democracy." (I. F. Stone, The Trial of

Socrates, p. 42).

After Philip of Macedon had enslaved the once free Greeks, his son Alexander

proceeded to make the world safe for Hellenic civilization. What democracy

had brought to birth was spread by methods by no means democratic. Greek

slaves abducted from their homeland taught the Romans who had captured

them how to sing praises to freedom. This paradox is not resolved by denying

the Greeks, nor the peoples who learned from them, their literacy.

|