|

There are many variations on this theme; classic mythology reminds

the reader of quantum mechanics, with its alternative endings. One version of the Prometheus

myth names this Titan as mankind's creator, a creative act for which

he was punished by a higher god, Zeus. This point,— who or what was

responsible for peopling the planet,— was curiously undecided in

pagan theology. Some of the pagans, who under the influence of philosophy

had begun shuffling toward monotheism, acclaimed Zeus as Creator God, an obvious

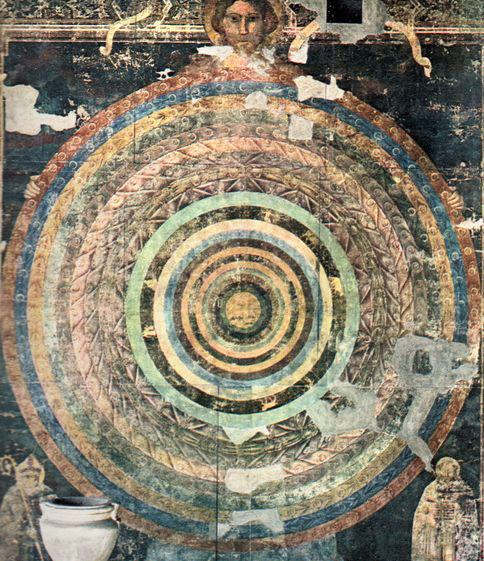

choice. But others did not. Proclus, a fifth century NeoPlatonic theologian, helpfully suggests, the sun,

moon and planets:

"For as that calls them to the war of generation, so

this in Plato excites them to the fabrication of mortals, which they

effect through motion. And this indeed is accomplished by all the

mundane Gods, but especially by the governors of the world [or the

planets], for they are those who are converted or turned, and in the most eminent degree by the sovereign sun."

(Proclus' Commentary on the Timaeus of Plato, translated by Thomas Taylor, Book V, p.

836).

This strange omission was noticed by Lactantius, a Christian author:

"But that the gods cannot be fathers or lords, is declared not only by

their multitude, as I have shown above, but also by reason: because it

is not reported that man was made by gods, nor is it found that the gods

themselves preceded the origin of man, since it appears that there were

men on the earth before the birth of Vulcan, and Liber, and Apollo, and

Jupiter himself." (Lactantius, The Divine Institutes, Book 4, Chapter

4).

Dio Chrysostom raises this theory, that the Titans were our

creators, not the Olympic gods who displaced them, "This explanation

I will now give to you, although it is very likely not at all

cheering, nor pleasing — for I imagine it was not devised to please

us — and it has something of the marvellous about it perhaps. It is

to the effect that all we human beings are of the blood of the

Titans. Then, because they were hateful to the gods and had waged

war on them, we are not dear to them either, but are punished by

them and have been born for chastisement, being, in truth,

imprisoned in life for as long a time as we each live. And when any

of us die, it means that we, having already been sufficiently

chastised,11 are released and go our way. This place which we call

the universe, they tell us, is a prison prepared by the gods, a

grievous and ill-ventilated one. . ." (Dio

Chrysostom, Discourse 30, 10-11). Dio does not himself

embrace this alternative theory; later in this same discourse he

scolds those who "insult the bounty of the gods." It was a

well-known fact of mythology that the Olympian gods had warred with

the Titans and overcome them, making it awkward to acclaim the

Olympians as our creators. Perhaps the Titans' loss was a loss for us as

well.

Our familiar theme of divided loyalties comes up, if our Creator should turn

out to be, not the high God, but a lesser luminary like Prometheus,

punished by Zeus for his indiscretion. This gnostic paradigm is thus

built into pagan theology, as is so much of the rest. In some versions,

women and men are not even offspring of the same fashioner:

"Prometheus son of Iapetus was the first to fashion men

out of clay. Later, Jupiter ordered Vulcan to make out of clay the

form of a woman, to whom Minerva gave life and the rest of the gods

their own personal gift. Because of this they named her Pandora. She

was given to Prometheus' brother Epimetheus in marriage, and they

had a daughter named Pyrrha, who is said to have been the first

mortal begotten by birth." (Hyginus' Fabulae 142)

Plato too took it for granted that mankind, at least in its physicality,

would be the creation of inferior gods, not of the high God: "All these the creator

first set in order, and out of them he constructed the universe, which

was a single animal comprehending in itself all other animals, mortal

and immortal. Now of the divine, he himself was the creator, but the

creation of the mortal he committed to his offspring. And they,

imitating him, received from him the immortal principle of the soul; and

around this they proceeded to fashion a mortal body, and made it to be

the vehicle of the soul, and constructed within the body a soul of another nature which was mortal, subject to terrible and irresistible affections. . ." (Plato,

Timaeus).

Just as in gnosticism, inquiring who created man, and to

whom therefore filial gratitude is due, is met with the answer, 'It's

complicated.' In some cases Zeus, not the original creator, nevertheless

re-establishes humankind after the flood:

"When the cataclysmus occurred, which we would call 'a

deluge' or 'a flood,' the entire human race perished except for

Deucalion and Pyrrha, who took refuge on Mount Aetna, which is said

to be the highest mountain on Sicily. When they could no longer

bear to live because of loneliness, they asked Jupiter either to give

them some more people or to kill them off with a similar

catastrophe. Then Jupiter ordered them to toss stones behind them.

Jupiter ordered the stones Deucalion threw to become men and those Pyrrha threw to become women."

(Hyginus' Fabulae 153).

So it's complicated, as complicated as when the bumbled production of

a fallen Demiurge is enlivened by Athena. Another pagan creation paradigm depicts man, not as the result of

an intentional act of creation on the part of an intelligent agent,

but as arising from the tears, blood, or other bodily fluids of an

immortal: "And one must have regard to the differences in our habits

and laws, or still more to that which is higher and more precious

and more authoritative, I mean the sacred tradition of the gods which

has been handed down to us by the theurgists of earlier days, namely

that when Zeus was setting all things in order there fell from him

drops of sacred blood, and from them, as they say, arose the race of

men." (Julian the Apostate, Letter to a Priest, Loeb edition, The

Works of the Emperor Julian, p. 307). Thus creation as an

'accident,' an inadvertent oversight, failure to clean up after

oneself, is also a normal theme of pagan theology. Finding these

themes in gnosticism can scarcely be surprising, realizing they are

normal for pagan polytheism, although not, of course, for

monotheism. The Egyptians also, some of the time, ascribed the creation of mankind to a

relatively minor god:

"Yet its main temple, built by the Ptolemies, was

dedicated to the ram-headed creator god Khnum, the god long believed

to have caused the Nile to flood and to have fashioned humans on his

potter's wheel — the very wheel still displayed in its own

shrine." (Cleopatra the Great, Dr. Joann Fletcher, p. 146).

Like the Greeks, the Egyptians were in some perplexity as to which of

their multitudes of gods, if any, was the creator:

"There are a variety of accounts of how Re created

the other gods who are personified in the various parts of creation. “One account pictures

him squatting on a primeval hillock, pondering and inventing names for various parts of

his own body. As he named each part, a new god sprang into existence. Another legend

portrays Re as violently expelling other gods from his own body, possibly by sneezing

or spitting. A third myth describes him creating the gods Shu and Tefnut by an act of

masturbation. These gods in turn gave birth to other gods.” Re, however, is not the

only god portrayed as creator in ancient Egypt. For example, the Memphite Theology

depicts Ptah as a potter creating the universe. In another text, the “Great Hymn

to Khnum,” the god Khnum is pictured as forming everything— man, gods, land animals,

fish, birds— on his potter’s wheel."

(Currid, John D. (2013-08-31). Against the Gods: The Polemical Theology of the Old

Testament (Kindle Locations 639-647). Crossway.)

So the idea that mankind owes gratitude for its existence, not to the highest

god who rules the world but to some lesser power, or to some act of magic

like Deucalion and his wife casting pebbles, is not novel in pagan

mythology. The place to look to unravel the mysteries of gnosticism is not

in monotheistic religion, but in paganism, from which this material is

borrowed. This theme of divided loyalties is inevitable in polytheism,

because some of these gods hate each other's guts. At a minimum, when you

venerate one, you make the others jealous; ask Paris how he got in

trouble judging their beauty contest. While it shocks

monotheist sensibilities to show ingratitude toward our own

creator, who gave us life, it might seem prudent to the pagan to

cozy up to the most powerful god, the one who can do you the most

damage, rather than to the insignificant bumbler who made you. The theme of protest or resentment against the failed,

incompetent or malevolent gods is richly represented in pagan lore: "'We

may here contrast the spirit of the Old and New Testaments with such

sentiments as this, on the tomb of a child: 'To the unjust gods who robbed

me of life;' or on that of a girl of twenty: '"I lift my hands against the

god who took me away, innocent as I am.'" (Alfred Edersheim, The Life and

Times of Jesus the Messiah, Book II, Chapter XI, Kindle location 5429). This theme is not so

commonly sounded in monotheism, because there is only one God and He is the

judge of all the earth.

It did not escape the notice of the first Christian generation

who encountered 'Christian' gnosticism that this material was

borrowed, wholesale:

"Much more like the truth, and more pleasing, is the account

which Antiphanes, one of the ancient comic poets, gives in his

Theogony as to the origin of all things. For he speaks of Chaos as

being produced from Night and Silence; relates that then Love sprang

from Chaos and Night; from this again, Light; and that from this, in

his opinion, were derived all the rest of the first generation of

the gods. After these he next introduces a second generation of

gods, and the creation of the world; then he narrates the formation

of mankind by the second order of the gods. These men (the

heretics), adopting this fable as their own, have ranged their

opinions round it, as if by a sort of natural process, only

the names of the things referred to, and setting forth the very same

beginning of the generation of all things, and their production." (Irenaeus,

Against Heresies, Book 2, Chapter 14, Section 1, p. 749, ECF_1_01).

Indeed, the gnostics took pagan religion and changed only the names.

That much is obvious. So why are they continually trying to market

this as a new and exciting version of Christianity?

|