Noetus

The modalist heresy first turns up in the second century. Far from being

of 'apostolic' origin, Hippolytus could recall the time of its introduction:

"There has appeared one, Noetus by name, and by birth a native of

Smyrna. This person introduced a heresy from

the tenets of Heraclitus." (Hippolytus,

Refutation of All Heresies, Book 9, Chapter 2).

"But in like manner, also, Noetus, being by birth a native

of Smyrna, and a fellow addicted to reckless babbling, as well as crafty withal, introduced

(among us) this heresy which originated from one

Epigonus." (Hippolytus,

Refutation of All Heresies, Book 10, Chapter 23).

Noetus affirmed that Jesus was His own Father and His own

Son: "Now, that Noetus affirms that the Son and Father are the same, no one is ignorant. But

he makes his statement thus: 'When indeed, then, the Father had not been born, He yet was justly

styled Father; and when it pleased Him to undergo generation, having been begotten, He Himself became

His own Son, not another's.'" (Hippolytus,

Refutation of All Heresies, Book 9, Chapter 5).

'Oneness' Popes of Blessed Memory: Zephyrinus

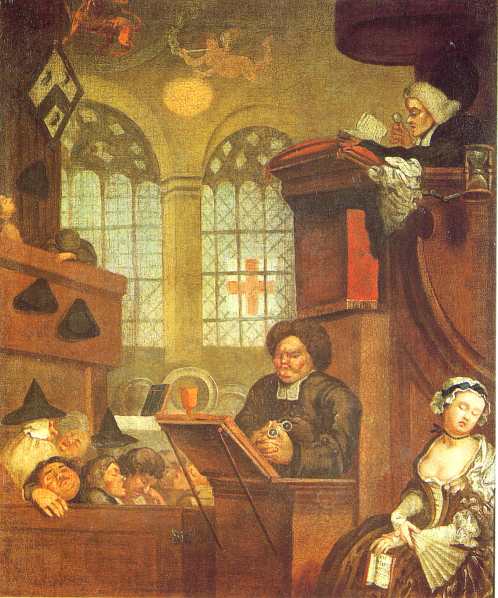

Hippolytus of Rome |

Two Bishops of Rome (a.k.a. Popes), Zephyrinus and

Callistus, are reported as modalists by Hippolytus, a well-placed contemporary observer. How

strange that 'Oneness' Pentecostals, so addicted to blistering anti-Catholic rhetoric, should trace

their heritage to two early Popes! These two Popes were reportedly forceful advocates for this

heresy: "The school of these heretics during the succession of such bishops, continued to acquire

strength and augmentation, from the fact that Zephyrinus and Callistus helped them to prevail."

(Hippolytus,

Refutation of All Heresies, Book 9, Chapter 2).

|

Sabellius

Because Sabellius is the most famed of the modalists,

Christians on first encountering 'Oneness' Pentecostals debate against Sabellian tenets

remembered from theology text-books. The response they hear is invariably a shocked, 'But we

don't believe anything like that!' Indeed, Sabellius' vocabulary, of Father "dilating" into

Son and Holy Spirit, is not commonly heard from the 'Oneness' crowd:

"Sabellius also raves in saying that the Father is Son, and again, the Son

Father, in subsistence One, in name Two; and he raves also in using as an example the grace of the

Spirit. For he says, 'As there are "diversities of gifts, but the same Spirit," so

also the Father is the same, but is dilated into Son and Spirit.'"

(Athanasius, Four Discourses Against the Arians, Discourse 4, 25).

"If then the Monad being dilated became a Triad, and the

Monad was the Father, and the Triad is Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, first the Monad being dilated,

underwent an affection and became what it was not; for it was dilated, whereas it had not been dilate.

Next, if the Monad itself was dilated into a Triad, and that, Father and Son and Holy Ghost,

then Father and Son and Spirit prove the same, as Sabellius held, unless the Monad which he speaks of

is something besides the Father, and then he ought not to speak of dilation, since the Monad was to

make Three, so that there was a Monad, and then Father, Son, and Spirit."

(Athanasius, Four Discourses Against the Arians, Discourse 4, 13).

Sabellius would appear to have been wholly innocent of the most objectionable

feature of modern 'Oneness' Pentecostalism, the identification of 'the

Son' as 'the flesh.' Hilary reports that a later modalist, Photinus,

criticized Sabellius for his failure to get with Pope Callistus' program:

"He [Photinus] castigates Sabellius for denying that the Son of God

is Man, and in his turn has to submit to the reproaches of Arian fanatics

for failing to see that this Man is the Son of God."

(Hilary of Poitiers, On

the Trinity, Book VII, Chapter 7).

In defense of the orthodoxy of the two 'Oneness' Popes

of Blessed Memory, Roman Catholics note that Callistus excommunicated Sabellius. But

Hippolytus says he did so out of fear: "Thus, after the death of Zephyrinus, supposing that he had

obtained (the position) after which he so eagerly pursued, he [Callistus] excommunicated Sabellius,

as not entertaining orthodox opinions. He acted thus from apprehension of me, and imagining

that he could in this manner obliterate the charge against him among the churches, as if he did not

entertain strange opinions." (Hippolytus,

Refutation of All Heresies, Book 9). In the present day, we do not observe fond feeling between heretics

of differing opinions: the Jehovah's Witnesses do not love the 'Oneness'

Pentecostals, who do not love the Mormons. Hippolytus does not ascribe

the same heresy to Sabellius and Callistus, but significantly different ones.

Pope Callistus I

Callistus was the innovator who introduced the definition

that 'the Son' means 'the flesh', i.e., the humanity, of Jesus of Nazareth: "For that which is

seen, which is man, he [Callistus] considers to be the Son; whereas the Spirit, which was contained in

the Son, to be the Father." (Hippolytus,

Refutation of All Heresies, Book 9, Chapter 7). This is the man!

This imaginative definition at the heart of modern-day

'Oneness' Pentecostalism was not part of Noetus' system; Hippolytus gives the credit to Callistus:

"Callistus corroborated the heresy of these Noetians, but we have already carefully explained

the details of his life. And Callistus himself produced likewise a heresy, and derived its

starting-points from these Noetians, -- namely, so far as he acknowledges that there is one Father and

God, viz., the Creator of the universe, and that this (God) is spoken of, and called by the name of

Son...And he is disposed (to maintain), that He who was seen in the flesh and was crucified is Son, but

that the Father it is who dwells in Him. Callistus thus at one time branches off into

the opinion of Noetus, but at another into that of Theodotus, and holds no sure doctrine."

(Hippolytus,

Refutation of All Heresies, Book 10, Chapter 23). So Hippolytus perceives Callistus' heresy, so similar to modern

'Oneness' Pentecostalism, as a blend between true modalism and the 'Unitarian Universalism' of the

day, promoted by Theodotus, who denied the Deity of Jesus Christ.

So we've found our first 'Oneness' believer, the third century Roman Pontiff Callistus! Sadly, there

is no historical evidence that he either spoke in tongues or introduced any innovative baptismal

formula. Thus even this 'Oneness' Pope of Blessed Memory cannot have been 'saved', by

'Oneness' Pentecostal standards. Could anyone, prior to 1913?

Tertullian

Tertullian, like Hippolytus, could recall when the "new-fangled" heresy of

modalism first hit town. He reports that Praxeas, against whom he defended the orthodox doctrine of

the Trinity, was the "first" to import modalism into Rome:

"...as, for instance, Praxeas. For he was the first to import into Rome from Asia this kind of heretical pravity,

a man in other respects of restless disposition, and above all inflated with the pride of confessorship simply and solely because he had

to bear for a short time the annoyance of a prison; on which occasion, even 'if he had given his body to be burned, it would have profiled

him nothing,' not having the love of God, whose very gifts he has resisted and destroyed. "

(Tertullian, Against

Praxeas, I).

"That this rule of faith has come down to us from the beginning of the gospel, even before any of the older heretics,

much more before Praxeas, a pretender of yesterday, will be apparent both from the lateness of date which marks all heresies, and also from

the absolutely novel character of our new-fangled Praxeas. In this principle also we must henceforth find a presumption of equal force

against all heresies whatsoever-that whatever is first is true, whereas that is spurious which is later in date."

(Tertullian, Against

Praxeas, II).

'Oneness' Pentecostals call Tertullian as hostile witness to testify against his own clear understanding that modalism was

a "new-fangled" heresy with his plaint that most believers of his day could not clearly

and affirmatively explain what it was they did believe, when challenged by heresy:

"The simple, indeed, (I will not call them unwise and unlearned) who

always constitute the majority of believers, are startled at the dispensation

(of the Three in One), on the ground that their very rule of faith withdraws

them from the world's plurality of gods to the one only true God; not understanding

that, although He is the one only God, He must yet be believed in with

His own economy ['oikonomia']. The numerical order and distribution of the Trinity they assume

to be a division of the Unity; whereas the Unity which derives the Trinity

out of its own self is so far from being destroyed, that it is actually

supported by it." (Tertullian, Against

Praxeas, III).

But it takes liberal use of white-out to blot out one of an author's statements

with another. If, as they claim, the author is 'lying' in one of his assertions,

why would he all of a sudden be forced to 'admit the truth' on the very

next page? To see all he says in context, download 'Against

Praxeas' from the Thrice Holy library. Once while a figure-skating competition

was playing on hellivision, the skater gave a little hop. As the commentator

helpfully explained, if you hop, then 'keep on hopping'—the judges might

be persuaded to see a choreographed move instead of a bobble or a misstep.

If Tertullian is purportedly 'lying' in his first statement, then he ought

to keep on 'lying'—not that the saints should lie at all, but who will

believe the initial 'lie' if he then reverses field and 'tells the truth'?

Rather, a more rational way to read the text is, not to negate one of the

author's statements with another, but to try to discern the intent of the

author, who made both statements.

The 'Oneness' Pentecostals assert that the reason the 'simple' were resisting

Tertullian's offer to help them vanquish Praxeas' "new-fangled"

heresy was because the 'simple' already embraced Praxeas' "new-fangled"

heresy, and indeed had always done so. But this interpretation is clearly

impossible,—how could Praxeas' heresy be "new-fangled" if 'the

majority of believers' already embraced it? How could Praxeas be the "first"

to introduce what everyone already believed? Praxeas was encountering sales

resistance among the 'simple' as he peddled his novel wares; but so was

Tertullian, as he offered his remedy for the malady Praxeas had introduced.

How could this be? It is scarcely an unusual situation. The crime victim

clutching his empty wallet may not be eager to go to the police for assistance,

even though cops fight robbers; many crimes go unreported, not because

victims share their victimizers' values or delight in having been robbed,

but because they fear or dislike the police, or for other reasons. Sick

people do not always rush to the doctor, even though doctors fight disease;

their resistance to swallowing the remedy the doctor prescribed is not

evidence of their fondness for cancer or whatever else ails them. Were

Iraqis disgusted at Saddam's tyranny obliged to embrace American troops

as liberators? Supposing people do not want what is behind Door No. 1;

does this mean they must eagerly embrace what is behind Door No. 2?

The 'simple' believed, as they had been taught, that there is only one

God, that the Father is God, that the Son is God, and that the Holy Spirit

is God. They would have been happy to go on so believing. But the heretics

warned them what they they had been taught was self-contradictory, and

they would have to choose. The Unitarian Universalists and the 'Oneness'

Pentecostals tell the 'simple' today they have to 'fudge' this one of these four

propositions: that 'the Son is God,' explaining that they really ought

to say, 'God was in the Son,' who is the 'flesh'. It wasn't the orthodox

who forced the issue, but the heretics. Tertullian wanted to teach the

'simple' a new vocabulary, which he had learned from Hippolytus, so that

they would not have to sit there tongue-tied when the heretics came by

to argue; but they resisted his gift, because it was new. The language

was new to them, but it wasn't new to God—it was in the book! As Tertullian

showed them, while his vocabulary was unfamiliar, it was nevertheless Biblical, and talking this

way was better than just sitting there making faces at the heretics.

Epiphanius shared Tertullian's anxiety about the "simple": "Then,

when they encounter simple or innocent persons who do not understand the

sacred scriptures clearly, they give them this first scare: 'What are we

to say, gentlemen? Have we one God or three gods?' But when someone who

is devout but does not fully understand the truth hears this, he is disturbed

and assents to their error at once, and comes to deny the existence of

the Son and the Holy Spirit." (The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis,

translated Frank Williams, Books II and III, Section IV, 2,6, Against Sabellians,

62, p. 122.) These authors' concern is not that the "simple"

already believed in one of the many anti-trinity heresies, whether modalism or

Theodotus' explicit denial of the deity of Jesus Christ, else where would

be the need to 'scare' them? Rather their experience was that some of the

"simple" 'assented' all too readily to these novel teachings upon first hearing, and those who did not assent maintained

a sullen silence, unable to defend their faith. The remedy they prescribed

is the same offered here at trisagionseraph.tripod.com, namely scripture.

Beryllus of Bostra

"Beryllus, whom we mentioned recently as bishop of Bostra in Arabia, turned

aside from the ecclesiastical standard and attempted to introduce ideas foreign to the faith.

He dared to assert that our Savior and Lord did not pre-exist in a distinct form of being of

his own before his abode among men, and that he does not possess a divinity of his own, but only

that of the Father dwelling in him. Many bishops carried on investigations and discussions

with him on this matter, and Origen having been invited with the others, went down at first for a

conference with him to ascertain his real opinion. But when he understood his views, and

perceived that they were erroneous, having persuaded him by argument, and convinced him by

demonstration, he brought him back to the true doctrine, and restored him to his former sound

opinion. There are still extant writings of Beryllus and of the synod held on his account,

which contain the questions put to him by Origen, and the discussions which were carried on in his

parish, as well as all the things done at that time." (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, Book VI, Chapter 33).

It's a toss-up whether to class Beryllus as a precursor to

Unitarian Universalism or to 'Oneness' Pentecostalism; the two come out much the same in

the end. Both assert that there is a mere man called 'the Son' who came into existence in the

days of King Herod, not having existed previously except as a 'plan' in the mind of 'the Father', who

alone is God. Both allow that this mere man was occasionally and voluntarily indwelt by 'the

Father', who alone is God, in similar manner to the prophets of old. Only 'Oneness'

Pentecostalism, though, adds the ghoulish touch of

the 'Ending

of the Sonship'; the Unitarians at least allow 'the Son' the eternal destiny common to the rest of mankind.

Montanists

The great apologist Tertullian belonged to this charismatic splinter group.

While Hippolytus counts some Montanists as followers of Noetus, most were

as orthodox as Tertullian. Some (though not all) of their number

prophesied...unfortunately, not always accurately! "In the wilds of

Phrygia, a Christian, Montanus, with several male helpers and two prophetesses,

began to speak the words of the Holy Spirit....By 177 [A.D.], the Spirit

was very widely known. "Lo!' it said, through Montanus, 'man is like

a lyre, and I strike him like a plectrum. Man is asleep, and I am

awake'...As critics agreed, Montanus' followers were not intellectual heretics.

They parted from fellow Christians only in their acceptance of the Spirit's

new words, and they persisted far into the sixth century, suffering legalized

persecution from their 'brethren.'...In one of the Spirit's 'oracles,'

a Montanist prophetess was said to have seen Christ, dressed as a woman,

and heard that 'here' (or 'thus') the 'new Jerusalem will descend.' She

believed, said the critics, that the reign of the Saints would begin at

Pepuza in Phyria, a site as bizarre as little Abonouteichos before it changed

its name. Unlike the new 'Ionopolis,' it remained Pepuza, a site

so obscure that it has eluded all attempts to find it on the map."

(Robin Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians, p. 405).

The failure of the heavenly Jerusalem to descend upon this obscure Asia Minor burg may invite charges of

false prophecy, but Montanism seems basically to have been a Back-to-the Bible reform movement.

Consequently, Tertullian has aptly been called 'the First Protestant.' Though evidently not gifted

himself, he had seen charismatic gifts in operation: "'Among us,' he wrote in Carthage,

'there is a "sister," gifted with revelations. She talks with angels, sometimes even with the

Lord.'...She sees and hears mysteries.'" (Quoted p. 410, op. cit.)

As noted, a subset of Montanists were also Noetians. This group still existed

in Jerome's day:

"In the first place we differ from the Montanists regarding the rule

of faith. We distinguish the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit as three

persons, but unite them as one substance. They, on the other hand, following

the doctrine of Sabellius, force the Trinity into the narrow limits of

a single personality." (Jerome, Letter 41.3).

An anonymous Latin treatise, 'Against All Heresies,' gives the name of

one of these people, Aeschines, the leader of this tendency: "But

the particular one they who follow Aeschines have; this, namely, whereby

they add this, that they affirm Christ to be Himself Son and Father."

(Against All Heresies, Chapter 7).

These people were 'two-fers': both charismatic and also modalist. There

is no evidence, however, that they employed any unusual baptismal formula.

Moreover, as Tertullian's testimony shows, it was not the normal expectation

that all members of the sect would be charismatically gifted, only some.

Donatists

The Donatists were not doctrinal innovators, but moral

rigorists concerned that believers who had abjured their faith under persecution should not be

readmitted to fellowship. "His [Augustine's] extensive polemics against the Donatists were on

the burning issues on which the latter separated from the Catholic Church. These were not what

are usually called doctrinal questions, for on such points as those on which Gnostics, Marcionites,

Arians, and Monophysites differed from the Catholic Church Donatists were in accord with the latter.

The contention, rather, as we have seen, was over the moral character of the priesthood and the

treatment which the Church should accord to those Christians who, having been guilty of serious

lapses, repented." (Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christianity, Volume I, p. 175).

Marcellus of Ancyra

Marcellus has been accused of denying the Trinity: "The followers

of Marcellus and Photinus...say that there is God, and the Logos, and the

Spirit. The Son, however, who is a man born of Mary, is a fourth

one, whom the Logos assumed. And they say that the Logos rules as

an administrator in this man, who was prepared as a dwelling for Him. Thus

do they destroy the Trinity. If, however, the Trinity is to remain,

there is one who is man and Logos: which Logos we have already demonstrated

above to be the Son." (Marius Victorinus, Against Arius, 905 [1, 45] c. 355 A.D.)

The traditional Christian understanding treats 'Son' and 'Word' as synonymous:

"On the contrary, Augustine says (De Trin. vi. 2): 'By Word we understand

the Son alone.' I answer that, Word, said of God in its proper sense, is

used personally, and is the proper name of the person of the Son. [...]

Hence Augustine says (De Trin. vii. 2): 'Word and Son express the same.'

For the Son's nativity, which is His personal property, is signified

by different names which are attributed to the Son to express His perfection

in various ways. To show that He is of the same nature as the Father,

He is called the Son; to show that He is co-eternal, He is called the Splendor;

to show that He is altogether like, He is called the Image; to show that

He is begotten immaterially, He is called the Word."

(Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, First Part Q. 34, Art. 2.)

By his own confession, Marcellus shares this traditional understanding:

"Now I, following the sacred scriptures, believe that there is one

God and his only-begotten Son, the Word, who is always with the Father

and has never had a beginning, but is truly of God -- not created, not

made, but forever existent, forever reigning with God and his Father, 'of

whose kingdom,' as the apostle testifies, 'there shall be no end.'"

(The Panarion of Ephiphanius of Salamis, Books II and III, translated by

Frank Williams, Section VI, 72, p. 425, A Copy of a Letter of Marcellus, 2,6.)

Nevertheless, Basil condemns Marcellus as a heretic: "He [Marcellus]

grants indeed that the Only begotten was called 'Word,' on coming forth

at need and in season, but states that He returned again to Him whence

He had come forth, and had no existence before His coming forth, nor hypostasis

after His return. The books in my possession which contain his unrighteous

writings exist as a proof of what I say." (Basil, Letters, 69:2, To

Athanasius).

"Sabellius the Libyan and Marcellus the Galatian alone of

all men have dared to teach and write these things which now those who

guide the people among you are trying to publish as their own

discoveries, babbling with their tongues and being incapable of

bringing these sophisms and fallacies into even a plausible

formulation." (Basil, Letter CCVII, p. 183, Loeb edition, St. Basil,

The Letters, Volume III.)

It would appear Marcellus was, or had been, unwilling to describe the pre-incarnate

Logos as 'Son': "'Now the Son also "is"; but Paul the Samosatian

and Marcellus took advantage of the text in the Gospel according to John,

"In the beginning was the Word." [John 1:1] No longer willing

to call the Son of God a true Son, they took advantage of the term, "Word,"

I mean verbal expression and utterance, and refused to say "Son of

God."'" (Letter of George, quoted p. 447, Epiphanius, Panarion,

Books II and III, Section VI, Against Semi-Arians, Chapter 53 (73), 12,1).

He was, in short, an exponent of the 'Incarnational Sonship,' which

Basil considers indistinguishable from modalism.

|