|

Inasmuch as Moses' law contains explicit 'equal protection'

language, one might think interpreting the law is a simple matter

of respecting this very clear language, and allowing God's will

to govern the matter. Except in those very few instances where

the lawgiver himself has limited the scope of application of a

given law, then the law applies without qualification to all who

fall under its sway. Reader, if you think so, you lack

imagination. It is possible to define several of the key words:

'stranger,' 'neighbor,' in such a way as to nullify the 'equal

protection' clause, and restore to the law the exclusivity the

Bible explicitly withholds. Thus the Rabbis did their 'apartheid'-style legislating on their

own authority.

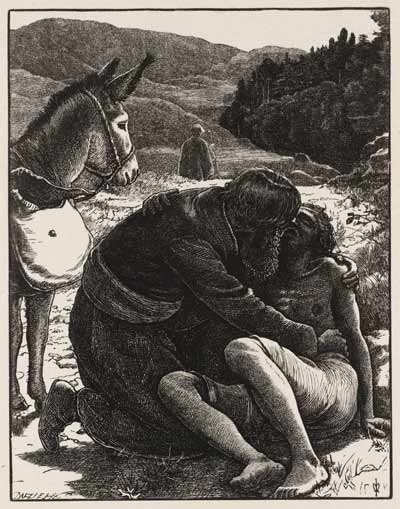

Who is my Neighbor?

The underlying issue is, who is the 'neighbor?' Rabbi Jesus answered

thusly:

"But he, willing to justify himself, said unto Jesus, And who is my neighbour? And Jesus answering said, A certain man went down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell among thieves, which stripped him of his raiment, and wounded him, and departed, leaving him half dead. And by chance there came down a certain priest that way: and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. And likewise a Levite, when he was at the place, came and looked on him, and passed by on the other side. But a certain Samaritan, as he journeyed, came where he was: and when he saw him, he had compassion on him, And went to him, and bound up his wounds, pouring in oil and wine, and set him on his own beast, and brought him to an inn, and took care of him. And on the morrow when he departed, he took out two pence, and gave them to the host, and said unto him, Take care of him; and whatsoever thou spendest more, when I come again, I will repay thee.

Which now of these three, thinkest thou, was neighbour unto him that fell among the thieves?

And he said, He that showed mercy on him. Then said Jesus unto him, Go, and do thou likewise."

(Luke 10:28-37).

It may be objected: why should moral opprobrium fall on the Rabbis, on grounds of adding an ethnic proviso to

laws where no such distinction is imposed by Moses, when they

are only acting by analogy with several other laws which already leave an exemption

for foreigners in the Old Testament text? For instance, "Unto a

stranger thou mayest lend upon usury; but unto thy brother thou

shalt not lend upon usury: that the LORD thy God may bless thee in

all that thou settest thine hand to in the land whither thou goest

to possess it." (Deuteronomy 23:20).

Charging interest on loans is one of those things which is

'on-the-bubble;' though all moralists would agree charging an

exorbitant interest rate is exploitive, neither participant in a

fair-rate money-lending contract, completed, need walk away

feeling damaged. Such undertakings can be mutually beneficial,

with both parties 'winning.' Though a pastoral, agrarian people might be

able to get by without it, easily available credit is the

life-blood of a mercantile economy. So Moses arrives at a split

decision: Israelites are called to the higher standard of

voluntary mutual benevolence, but allowed to

transact ordinary business with others.

So is money-lending allowed, or

disallowed? It depends. To whom are you lending? Thus we find:

"MISHNAH. ONE MAY NOT ACCEPT FROM AN ISRAELITE AN

'IRON FLOCK' [INVESTMENT WITH COMPLETE IMMUNITY FOR THE

INVESTOR], BECAUSE THAT IS USURY. BUT SUCH MAY BE ACCEPTED FROM

HEATHENS. AND ONE MAY BORROW FROM AND LEND TO THEM ON INTEREST.

THE SAME APPLIES TO A RESIDENT ALIEN." (Babylonian Talmud,

Tractate Baba Mezia, 70b.)

One can argue around the edges; perhaps there is

permission-creep from foreigners to residents, but the basic

plan: foreigners OK, brethren not, is in this instance Biblical. But wait: the

Messiah legislates for His people: "For he taught them as one

having authority, and not as the scribes." (Matthew 7:29). Those

who do not concede the Messiah's authority might well reason,

inasmuch as an ethnic proviso is attached to some of Moses' laws,

where there occurs a term subject to interpretation, like

'neighbor,' an ethnic interpretation is not disallowed. Without

the Lord's definition of 'neighbor' to enlighten the discussion,

these racialist interpretations are not self-evidently wrong.

But isn't this precisely the point. Yes, Virginia, there is a

non-racialist and non-xenophobic version of Judaism which is not

an embarrassment to read: it's called 'Christianity.'

There is a fad in the publishing industry right now, the 'Jewish

Jesus.' (Probably they did not get the memo from the 'Jesus Seminar'

about the' Cynic Sage Jesus.') Authors like Rabbi Shmuley Boteach offer

a celebratory portrayal of the Talmud, with all the racialism

air-brushed out. What comes next: because the Talmud, a sixth

century compilation which may, in some cases, reflect the

convictions of earlier Pharisees, is so wonderful, the New

Testament, which does not depict Jesus as the Pharisee He surely

must have been, is a tissue of lies and must be discarded.

It is only fair to point out, in response: the Talmud is not so very

wonderful, certainly not to the point that Jesus' teaching is

redundant. There already does seem to be some of Jesus' influence

felt in the Talmud (though of course He is never quoted by name);

would that there were more. Some of the Rabbis do seem to have been

listening to the Sermon on the Mount; take, for instance, ". .

.R. Eleazar of Modin (c. A.D. 120) said that there is no need to

provide for to-morrow, to gather wealth; have faith, and God will

not forsake you. . ." (W. D. Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism,

p. 221). On non-retaliation: "Has it not been taught: Concerning those

who are insulted but do not insult others [in revenge], who hear

themselves reproached without replying, who [perform good] work

out of love of the Lord and rejoice in their sufferings,

Scripture says: But they that love Him be as the sun when he goeth forth in his might?"

(Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Yoma,

23a). Even Rabbi Akiba is not immune:

"Thus Rabbi Akiba pointed to the golden rule as the

most comprehensive teaching of the Torah. "This is the most

fundamental principle enunciated in the Torah," he taught, "'Love

thy neighbor as thyself'" (Lev. 19:18)."

(Rabbi Ben Zion Bokser, Ben. The Wisdom of the Talmud (Kindle

Locations 1545-1546).)

How does he know that Leviticus 19:18 is the most fundamental

principle, when it is not specially demarcated as such? He could have

heard it from Jesus' followers. Compare this story, "R. Johanan b. Zakkai said: This may be

compared to a king who summoned his servants to a banquet without

appointing a time. The wise ones adorned themselves and sat at

the door of the palace. ['for,'] said they. 'is anything lacking

in a royal palace?' The fools went about their work, saying, 'can

there be a banquet without preparations'? Suddenly the king

desired [the presence of] his servants: the wise entered adorned,

while the fools entered soiled. The king rejoiced at the wise but

was angry with the fools. 'Those who adorned themselves for the

banquet,' ordered he, 'let them sit, eat and drink. But those who

did not adorn themselves for the banquet, let them stand and

watch.'" (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbath 153a). Compare with the

parable of the wise virgins, or,

"And when the king came in to see the guests, he saw there a man which had not on a wedding garment:

And he saith unto him, Friend, how camest thou in hither not having a wedding garment? And he was speechless."

(Matthew 22:11-12).

Inasmuch as Jesus is earlier and Johanan ben Zakkai later,

there would ordinarily be no question as to who is influencing

whom. This would be an interesting, but unfortunately grossly neglected

study. There are numerous synergies or convergences, "The same [Rabha]

said again: 'The man who lends his money is more deserving than the

charitable man, and the most deserving of all is he who gives charity

surreptitiously or invests money in partnership (with the poor.)"

(The Babylonian Talmud, Volume I, Tract Sabbath, edited by Michael L. Rodkinson, Kindle location 3299). Jesus too instructed that the left hand

not know what the right hand was doing. Likewise, "Thence thou canst

learn, that everyone who maketh himself humble is raised up by the

Holy One, blessed be He, and one who is arrogant is humbled by the

Holy One, blessed be He." (The Babylonian Talmud, Volume III, Section Moed, Tract Erubin, Chapter 1, edited by Michael L. Rodkinson, Kindle

location 9467). This is reminiscent of, "And whosoever shall exalt

himself shall be abased; and he that shall humble himself shall be

exalted." (Matthew 23:12), which in its turn, recalls the Magnificat,

based on Hannah's song.

The possibilities are several: given that everything in the Talmud is, technically, later than the New

Testament, these thoughts are influenced by Jesus of Nazareth, or,

they derive from the common source, the Old Testament, or they are

independently revealed or learned by reason. Which is it here?: "There is a Boraitha:

R. Mair said: The measure with which one measures will be measured

out to him — i.e., as man deals, he will be dealt with, as it reads [Isa. xxvii. 8]: 'In measure, by driving him forth, thou strivest with him.'"

(The Babylonian Talmud, edited by Michael L. Rodkinson, Volume XVI, Tract

Sanhedrin, Chapter XI, Kindle location 65332). The commonly stated

sequence, that Jesus is borrowing from the Rabbis of the Talmud and

was in fact quite unoriginal, unfortunately makes the time line run

backwards! Students of the Talmud differ in their estimation of the

integrity of its process of compilation; some take the

attributions of sayings to various Rabbis at face value, and

since personal authority is taken as a significant factor in

weighing, this is the charitable tack to take. What is mysterious

is when a third century A.D. Rabbi who says, again, something

that Jesus had said is produced, triumphantly, by the critics as

proof positive that Jesus was unoriginal. Better to let the clock run

clockwise, as it is prone to do.

We cannot see the whole narrative unfold before us, rather as

the strobe light flashes, we catch sight of set-pieces widely

separated in time. Jesus' teaching was controversial in His own

time, the New Testament teaches. 'Impossible!' proclaims the

anti-missionaries. Why? Because centuries later, these same

points were not controversial but widely accepted. If this were not a

common pattern in the acceptance of new social and political

ideas, it might seem problematical.

|