Proskynesis

This word,-- 'proskynesis',- is the very word the translators of the Septuagint saw fit

to use in translating the second commandment: "Thou shalt not make to thyself an idol, nor

likeness of anything, whatever things are in the heaven above, and whatever are in the earth beneath,

and whatever are in the waters under the earth. Thou shalt not bow down ['proskuneo'] to them, nor serve ['latreuo']

them; for I am the Lord thy God, a jealous God, recompensing the sins of the fathers upon the children, to the third and fourth

generation to them that hate me..." (Exodus 20:4-5, Brenton Septuagint). Exactly what God forbade: bowing

down ['proskuneo'] before graven images -- is precisely what Empress Irene's Council legalized!

"Woe to those who call evil good, and good evil; who put darkness

for light, and light for darkness; who put bitter for sweet, and sweet

for bitter!" (Isaiah 5:20). Bowing before images was common enough in pagan worship, as here in a besieged city: "From Trebonius's camp and all the higher grounds it was easy to see into the town — how all the youth which remained in it, and all persons of more advanced years, with their wives and children, and the public guards, were either extending their hands from the wall to the heavens or were repairing to the temples of the immortal gods, and, prostrating themselves before their images, were entreating them to grant them victory." (Julius Caesar, The Civil War, Book II, Chapter V).

God does not allow bowing down and forbid

serving, He says you shall do neither one nor

the other: "And the Lord made a covenant with them, and charged them,

saying, Ye shall not fear other gods, neither shall ye worship ['proskuneo'] them, nor serve ['latreuo'] them,

nor sacrifice to them: but only to the Lord, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt with great strength and with a high arm:

him shall ye fear, and him shall ye worship; to him shall ye sacrifice."

(2 Kings 17:35 Brenton Septuagint).

Roman Catholics claim 'proskynesis' is a lower form of worship than 'latreia,' the latter being reserved for God but the former available to the creature.

But the way the Bible uses these Greek words does not reflect any intent

to set up a two-tier scheme of worship. The Roman Catholics themselves

translate 'proskuneo' in Matthew 4:10 as "worship." Satan

demanded 'proskynesis' not 'latreia,' eliciting this rebuke from the Lord: "Then Jesus replied, 'Be off, Satan!

For scripture says: You must worship ['proskuneo'] the Lord your God, and serve him alone.'"

(Jerusalem Bible).

See the handsprings the flexible lexicographers must perform: "In many verses in

the New Testament, προσκυνεω is used to refer to the stance one is to have

in exclusive relationship to God (e.g., Matt. 4:10, Luke 4:7-8). When

used in this sense, προσκυνεω expresses submission to God's supreme

and ultimate authority." (Karen H. Jobes, Biblical Words and Their Meaning, Moises Silva,

Kindle location 2958). So here we have a general rule to which one

makes exception whenever one pleases, by redefining the operative term?

'You must worship God alone, though of course you can 'worship'

whatever you like.' This would be no rule at all, yet plainly, there it is.

It is like reading in a news report, 'Joe murdered Jack.' 'But

you're not supposed to murder! It must mean, "tapped lightly on the

shoulder."'

The background of these words in classical Greek is that 'proskynesis' means 'worship,' 'latreia' means 'menial

service': "proskuneo...to make obeisance to the gods, fall down and worship, to worship, adore..."

(Liddell &

Scott); "latreia...the state of a hired workman, service, servitude"

(Liddell & Scott); "latreuo,

to work for hire or pay, to be in servitude, serve..."

(Liddell & Scott). Part of what was wrapped up with proskynesis was prostration,

i.e., a face-plant. When Themistocles intended to present himself to the Persian king as

a suppliant, he went first to Artabanus the chiliarch, who read him the

rules:

"He replied, 'Stranger, the customs of different races are

different, and each has its own standard of right and wrong; yet among

all men it is thought right to honor, admire, and to defend one's own

customs. Now we are told that you chiefly prize freedom and equality;

we on the other hand think it the best of all our laws to honor the

king, and to worship him as we should worship the statue of a god that

preserves us all. Wherefore if you are come with the intention of

adopting our customs, and of prostrating yourself before the king,

you may be permitted to see the king, and speak with him; but if not,

you must use some other person to communicate with him; for it is not

the custom for the king to converse with any one who does not prostrate

himself before him.'" (Plutarch, Life of Themistocles, Chapter XXVII,

Plutarch's Lives, Volume I, p. 143).

But there was more. The literal meaning of the word is roughly 'make like a dog,' originally referring to a peculiar

gesture employed by the pagans: kissing the hand, then blowing

the kiss toward the object of adoration, sort of the way a dog

licks its master's hand. Job seems to be referring to the gesture:

"If I beheld the sun when it shined, or the moon walking in brightness;

And my heart hath been secretly enticed, or my mouth hath kissed

my hand:..." (Job 31:26-27). "...the payer of 'proskynesis'

would bring a hand, usually his right one, to his lips and kiss the tips of his fingers, perhaps blowing

the kiss towards his king or god, though the blowing of kisses

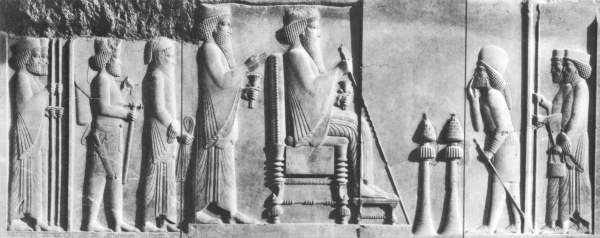

is only known for certain in Roman society. In the carvings of

Persepolis, the nobles mounting the palace staircase or the attendants

on King Artaxerxes's tomb can be seen in the middle of the gesture,

while the Steward of the Royal Household kisses his hand before

the Great King, bending slightly forwards as he does so. These

Persian pictures and the Greeks' own choice of words show that

in Alexander's day, 'proskynesis' could be conducted with the body upright,

bowed or prostrate...In Greece it was a gesture reserved for the

gods alone, but in Persia it was also paid to men..." (Robin Lane

Fox, Alexander the Great, pp. 320-321).

Alexander the Great 'went Persian' according to Arrian, "For the

tale goes that Alexander even desired people to bow to the earth

before him, from the idea that Ammon was his father rather than

Philip, and since he now emulated the ways of the Persians and

Medes, both by the change of his garb and the altered arrangements

of his general way of life." (Arrian, Anabasis, Book IV, Chapter

IX). When Alexander demanded worship from his subjects,— 'proskynesis'—

they understood him to be demanding, not the honor a monarch might reasonably expect from the populace,

but divine honors: "It is true that in Greece 'proskynesis'

was only paid to the gods, and that Alexander was doubtless aware of this...he had been wearing the

diadem, which among Greeks was a claim to represent Zeus...It

was to be the same with 'proskynesis': his own Master of Ceremonies

described the first attempt to introduce it and as the incident

took place at a dinner party, he would have been present in the

dining-room and able to see the result for himself...Then they

went Oriental: they paid 'proskynesis' to Alexander, kissing their hand and

perhaps bowing slightly...This unassuming little ceremony went

the round of all the guests, each drinking, kissing his hand and

being kissed in return by the king, until it came to Callisthenes,

cousin of Aristotle. He drank from the cup, ignored the 'proskynesis'

and walked straight up to Alexander, hoping to receive a proper kiss...Alexander refused to kiss him.

'Very well,' said Callisthenes, 'I go away the poorer by a kiss.'"

(Robin Lane Fox, Alexander the Great, pp. 322-323). This poverty

of a kiss would cost Callisthenes his life; he was executed as

a traitor. Even a pagan like Callisthenes aware one should not

offer 'proskynesis' to a mortal, while Roman Catholics

are not aware of this!

What would the sputtering Macedonian have said about Alexander? Something like this:

"For as soon as the king gave orders that he should be saluted as the son of Jupiter, Hegelochus, indignant at that, said: 'Are we then to recognize this king, who disdains Philip as his father? It is all over with us if we can endure that. He scorns, not only men, but even the gods, who demands to be believed a god. . .Have we at the price of our blood created a god who disdains us, who is reluctant to enter into council with mortals?'" (Quintus Curtius Rufus, History of Alexander, Book VI, Section 23-24).

This indictment, of blasphemy and presumption, is the common lot of men who claim to be gods; even Jesus, wholly innocent, was taken for a blasphemer. It is not understood to be 'business as usual' for a human being to receive divine worship.

|